‘The point is to get disoriented, not oriented’: David Reinfurt on why it’s time to rethink how we teach design

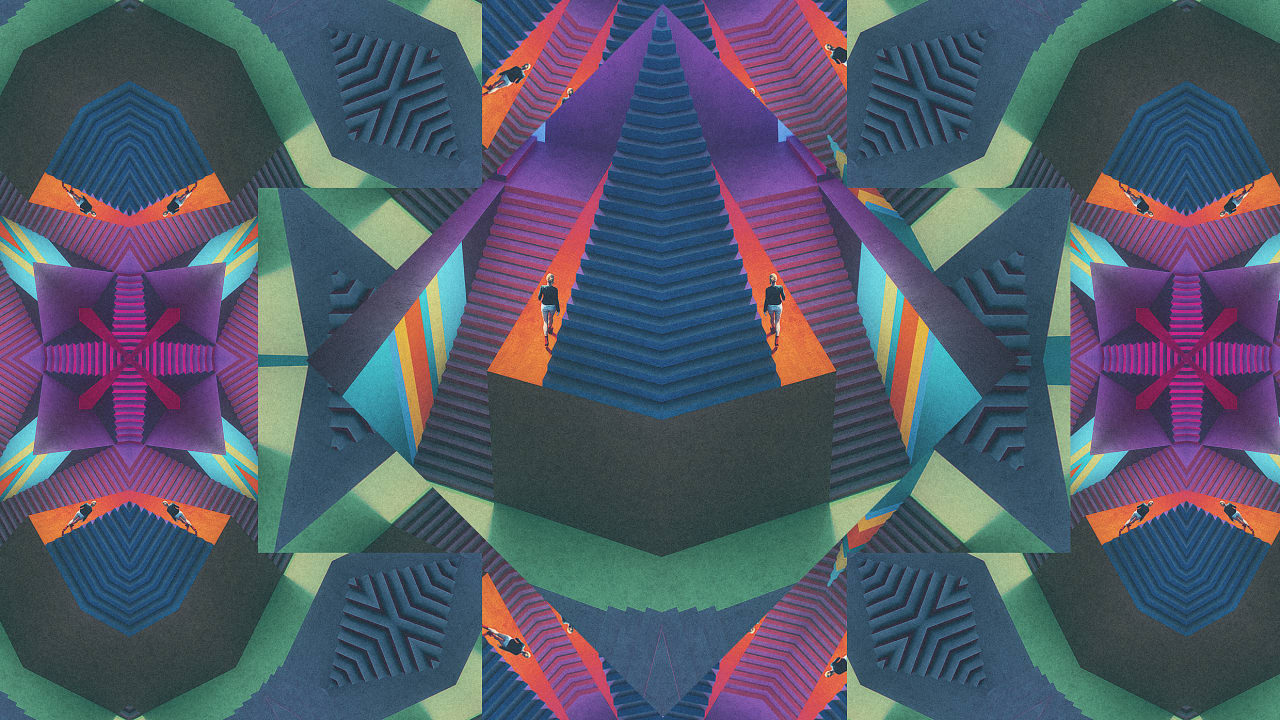

Designer, editor, and educator David Reinfurt’s 2019 book, A *New* Program for Graphic Design (Inventory Press) was a surprise success, selling out its initial print run in three weeks. It’s now in its third edition with translations in Chinese, French, German, Italian, Korean, and Spanish. The book was described as a “do-it-yourself textbook,” but a traditional design textbook it was not. Across its three chapters—Typography, Gestalt, and Interface—Reinfurt draws on designers, printers, artists, and publishers to show that graphic design is not a narrow area of study but rather a broad way of looking at how we understand the world. The creation of the book, too, was as unusual as its contents. The three chapters were based on three courses Reinfurt had been teaching at Princeton University. To produce the book, Reinfurt presented all his lectures from all three courses to an audience at Inventory Press’s studio in Los Angeles. Transcripts were produced from the three days that were then edited to form the book, making for a casual, dialogue-driven text that is at once personal, meandering, and expansive. [Cover Image: Inventory Press] Now, Reinfurt and Inventory Press are releasing a follow-up book, A *Co-* Program for Graphic Design, that is based on three of Reinfurt’s new courses: Circulation, Multiplicity, and Research. Reinfurt taught these courses over Zoom, during the pandemic, and much like the first book, used the recordings from those sessions as the structure for the new book. Because of the limitations and opportunities of teaching over Zoom, A *Co-* Program introduces a series of new voices, guest lectures from each course, which further expand our understanding of what graphic design can be. In a moment where graphic design is undergoing profound change, I find this pair of books to help situate both what it means to be a graphic designer and what it means to teach graphic design. Reinfurt, I think, offers a timeless approach to graphic design that transcends technical skills, industry demands, and visual fads in favor of treating design as a serious area of study that blends disciplines and ways of thinking. I was curious to talk with him about the ideas in the books and why graphic design, as a term, is still a useful framing device. Much like the creation of the books themselves, this conversation was conducted over Zoom and edited for clarity. And like their content, this conversation meanders and moves, attempting to find new ways to teach graphic design. Fast Company: I want to begin by talking about the title of this book. You open A *Co-* Program for Graphic Design with a list of all the alternative titles you had come up with and a roundtable conversation with some former students about what “Co-program” means. I want to ask you about the other part. I want to ask you about “graphic design.” What is graphic design? You have to find a place to locate yourself. Over the years, I’ve worked between a lot of different areas, but my training was in graphic design and I hang on to that as a label. But you’re asking what graphic design is. That term has been around at least for enough time to gather some historical weight, and I like that, too. The first book was originally going to be titled A New Primer for Visual Literacy, as a play on Donis Dondis’s Primer of Visual Literacy, but we decided to rename it because it didn’t feel like a good idea to riff on a previous book. We landed on A *New* Program for Graphic Design, which I liked a lot. People know the term graphic design. People are often confused about it, but at least it’s familiar. I like this idea of graphic design being a way to locate yourself. You’ve called yourself a graphic designer for about 25 years now. Has your understanding of graphic design changed over your career? Does it mean something different to you now than it did when you started? I’m certain it does, but I don’t worry about that too much. It’s a way to identify where I’m coming from and probably where my work is the most legible. But I love the idea of a bait and switch. I don’t mean that as a trick. I find it’s really useful to be able to give someone a way into the work and then have it become more complex than they’re expecting, because it’s so unsatisfying when it’s the reverse, right? The reason I asked you those first two questions is that I think that’s exactly what you do in these books: you complicate our understanding of what graphic design can be. In the first book, you talk about graphic design as the “most liberal of the liberal arts” and offer an assortment of definitions throughout both books. I think it’s interesting that this term has all of these different definitions or approaches or ways into it or ways out of it. When you were first invited to teach a graphic design class at Princeton 15 years ago, how did that blurriness or elasticity shape how you thought about what that would mean to teach graphic

Designer, editor, and educator David Reinfurt’s 2019 book, A *New* Program for Graphic Design (Inventory Press) was a surprise success, selling out its initial print run in three weeks. It’s now in its third edition with translations in Chinese, French, German, Italian, Korean, and Spanish. The book was described as a “do-it-yourself textbook,” but a traditional design textbook it was not. Across its three chapters—Typography, Gestalt, and Interface—Reinfurt draws on designers, printers, artists, and publishers to show that graphic design is not a narrow area of study but rather a broad way of looking at how we understand the world.

The creation of the book, too, was as unusual as its contents. The three chapters were based on three courses Reinfurt had been teaching at Princeton University. To produce the book, Reinfurt presented all his lectures from all three courses to an audience at Inventory Press’s studio in Los Angeles. Transcripts were produced from the three days that were then edited to form the book, making for a casual, dialogue-driven text that is at once personal, meandering, and expansive.

Now, Reinfurt and Inventory Press are releasing a follow-up book, A *Co-* Program for Graphic Design, that is based on three of Reinfurt’s new courses: Circulation, Multiplicity, and Research. Reinfurt taught these courses over Zoom, during the pandemic, and much like the first book, used the recordings from those sessions as the structure for the new book. Because of the limitations and opportunities of teaching over Zoom, A *Co-* Program introduces a series of new voices, guest lectures from each course, which further expand our understanding of what graphic design can be.

In a moment where graphic design is undergoing profound change, I find this pair of books to help situate both what it means to be a graphic designer and what it means to teach graphic design. Reinfurt, I think, offers a timeless approach to graphic design that transcends technical skills, industry demands, and visual fads in favor of treating design as a serious area of study that blends disciplines and ways of thinking. I was curious to talk with him about the ideas in the books and why graphic design, as a term, is still a useful framing device. Much like the creation of the books themselves, this conversation was conducted over Zoom and edited for clarity. And like their content, this conversation meanders and moves, attempting to find new ways to teach graphic design.

Fast Company: I want to begin by talking about the title of this book. You open A *Co-* Program for Graphic Design with a list of all the alternative titles you had come up with and a roundtable conversation with some former students about what “Co-program” means. I want to ask you about the other part. I want to ask you about “graphic design.” What is graphic design?

You have to find a place to locate yourself. Over the years, I’ve worked between a lot of different areas, but my training was in graphic design and I hang on to that as a label.

But you’re asking what graphic design is. That term has been around at least for enough time to gather some historical weight, and I like that, too. The first book was originally going to be titled A New Primer for Visual Literacy, as a play on Donis Dondis’s Primer of Visual Literacy, but we decided to rename it because it didn’t feel like a good idea to riff on a previous book. We landed on A *New* Program for Graphic Design, which I liked a lot. People know the term graphic design. People are often confused about it, but at least it’s familiar.

I like this idea of graphic design being a way to locate yourself. You’ve called yourself a graphic designer for about 25 years now. Has your understanding of graphic design changed over your career? Does it mean something different to you now than it did when you started?

I’m certain it does, but I don’t worry about that too much. It’s a way to identify where I’m coming from and probably where my work is the most legible.

But I love the idea of a bait and switch. I don’t mean that as a trick. I find it’s really useful to be able to give someone a way into the work and then have it become more complex than they’re expecting, because it’s so unsatisfying when it’s the reverse, right?

The reason I asked you those first two questions is that I think that’s exactly what you do in these books: you complicate our understanding of what graphic design can be. In the first book, you talk about graphic design as the “most liberal of the liberal arts” and offer an assortment of definitions throughout both books. I think it’s interesting that this term has all of these different definitions or approaches or ways into it or ways out of it. When you were first invited to teach a graphic design class at Princeton 15 years ago, how did that blurriness or elasticity shape how you thought about what that would mean to teach graphic design?

First, I knew it needed to be an introductory class. What’s the basic skill that’s useful in graphic design? Where do you start? Typography seemed like it. Design has been taught that way for a long time. There’s a historical weight to it; there are a set of skills that come with it, and that seemed like a way to introduce graphic design to the campus that could open up other modes of thought.

You write in the first book that graphic design is often taught just as a series of skills, and that you feel like that shortchanges what it means to teach graphic design. Can you tell me more about that?

In my experience, design education should not be training for a job. If you want to learn practical skills, you can find them in many different ways. But I think in school, the point is to get disoriented, not to get oriented. I feel like in school, you should just have all these crazy ideas and facilitate those because the rest of your working career is going to try to limit that. We’re doing a disservice to train a student for a job. I don’t know what the jobs will be. I don’t just want to see more designers like what we already have. I want to see more designers who are surprising and crazy and can make a go of it for a whole career.

If you think about typography, for example, you’re thinking about both what it says and how it says it. I don’t just mean rhetorically, but visually: a visual form conveys a lot of meaning. This is something every graphic designer knows. It’s pretty easy to understand how “hello,” written in sans serif, bold, condensed, means something very different than “hello” in a lowercase script. These lessons of how you can modulate a meaning with form, I think, are a good entryway into graphic design. It is a set of skills that could get you a job, but I also see it as a useful skill that’s applicable across many different disciplines. It introduces a rigor in the way you think—it’s a rigor that thinks about how a message is embodied.

Building on that, there’s almost no mention of technology in these books. Where does technology—the computer, ways of production or making—come into the classroom?

I keep students off the computer as long as possible, because you realize how they loosen up when they’re working with their hands. Plus, it’s going to change, right? The technology will never be the same and everyone will use it slightly differently. When I’m giving assignments, they are meant to be broad. I want to signal “Hey, this is something different. You can loosen up. You can do it a different way.” I’m predisposed to leaving things open for the student—or reader—to find their way through it, regardless of the technology.

Let’s get into some of the specific content in the book. I think of your first book as being about production and the second book as about distribution. The chapters in the first book—Typography, Gestalt, Interface—are all about how you put ideas into the work and then the chapters in the second book—Circulation, Multiplicity, Researcher—are all about how those ideas go out into the world. Does that sound right to you?

That wasn’t intentional, but it sounds right. At least since going to graduate school, I’ve been interested in that second part. I would see design in the world and realize how multiplied the responses were: it can be torn in one situation or somebody writes on top of it or puts a sticker on it. Those things are fascinating to me. I realized the work is not done when you’re finished doing the work, the work is done when it’s done being used. I have always felt like that part of design was ignored because it’s not as tidy. I’m not very interested in the monic idea of what it’s supposed to be. I’m endlessly interested in all the individual variations: if it’s been altered, or if it doesn’t land the right way.

The first chapter in the book begins with the Black Lives Matter typography because I was interested in how you could write it in ways that rhyme visually, rhyme with each other, but weren’t exactly the same. In that way, it felt like a brand, but it wasn’t organized from the top down.

The book opens with the Black Lives Matter typography and ends with a chapter about research. I felt like Research could have been the title of every chapter because the argument you implicitly make here is that all design is a form of research.

I was interested in doing a class on design research because I’d heard that term bandied about a bunch of different ways over time and wanted to look at how it was talked about at different points in time.

To think about all design as research gives you more latitude as a designer to spend more time making things that might not satisfy what needs to be done. To get to the best work, you have to go through a bunch of hoops, and you should follow your intuition. I think that’s what you bring to a project as a designer. So when I’m talking about research, I’m really talking about design process: how do you cultivate your own idiosyncratic, wasteful, digestive process?

Both of these books are filled with design history: you jump back and forth through time, looking at different people, looking at different projects, looking at different ways design has been understood. What is the role of design history in your teaching?

I want to find some exemplary practices that I can use as models. It can be powerful to pull examples from the past—from a time that is not right now—so you can inject a bit of critical distance. You can say, “We don’t really work like this anymore but here is one approach. Here is one way someone approached this problem. How does this resonate with what we’re doing?”

As a student, you can look at that and realize that you could also invent an equally novel way of approaching this work now. I instinctively think it’s useful to have heroes or role models that you can look to and think, “Here’s somebody who approached their work in a way that really resonates with me. How am I the same or different?”

I keep hearing conversations about the death of graphic design. That it’s being replaced by product designers or brand strategists or creative technologists, or some other new term. History becomes another way to root contemporary work in a discourse.

Yes. This goes back to our discussion of why identify it as graphic design rather than something else, and it just reinforces my opinion that it’s useful to connect what we’re doing now to a body of what people have done before. If we’re constantly changing what it’s called, it just goes poof, up in the air.

A good and useful model that has a much richer discourse than graphic design is architecture. Architecture has shifted what the profession does so radically and architects are very good at claiming lots of territory that doesn’t always look like architecture as we narrowly define it. An obvious example is what OMA has done with AMO in making research a valid output of their studio. Lots of people do that kind of work, but doing it within the context of architecture gives it previous discourse in history to anchor it in. I think in graphic design, we’ve built that discourse in history, and it is useful to connect these expansive practices to that so students can see a range of opportunities.

Architecture is a good example here because we often think of architecture narrowly as “buildings,” but AMO or any other architect working outside of that context often describes their work more broadly as a “spatial practice.” Architecture, then, isn’t just about making a building but larger questions of how we relate to things in space. When you think about it that way, you could make a building, but you could also make a film or an exhibition or a temporary structure, and they all connect to these larger questions of space. Does graphic design have something like that to root itself? Is it too simple to say something like “text and image”?

I do think there’s a core there and it’s close to text and image, but I’d define it as language and its form: how something is said, and the visual form that carries that. Text and image can seem like categories, where the language and the form or something feel like a rich place for discovery.

How has teaching affected how you work on other projects? Has it changed how you think about design? Has it changed how you work?

Surely it has. Teaching doesn’t harden up how you think about your work, but instead gives you 85 different ways of talking about it. It gives you lots of perspectives. When I first started teaching, I would not talk about my own work. I wouldn’t even introduce who I was or where it’s coming from. But as I got into it, I realized it can be generous to acknowledge my viewpoint. Here are the things I like to do. Here’s something I was working on last week. I can speak about those things with lots of detail, and that’s more genuine than speaking about something I don’t know about.

I have always thought about teaching and practice being one continuous thing. The only way teaching made sense to me was to make it similar to how I think about design. I’m interested in how to make a continuous process and make kind of everything I’m doing speak to the other parts of it. Maybe this is a self-preservation device. Maybe that’s why I’ve been able to work independently for a long time.

Tell me about your own design education. You have a BA in Visual Communication from UNC-Chapel Hill and an MFA in Graphic Design from Yale. How did they shape your understanding of all of this?

What I took from my undergraduate education was the freedom to just jump across departments. I was taking math and journalism and English and studio art. I found that liberating. There is a lot that I also took from Yale. I was totally disoriented. Not everyone could make sense of what I was doing, but it didn’t matter because they’re enthusiastically encouraging you to do it your own way.

That sounds like it also speaks to the longevity of your independence and how you operate in the classroom. It’s not about developing a specific set of skills to get you a job but developing a point of view to guide your work. That’s basically what these books are about, too.

Hindsight makes it easier to make that connection, but I’m sure that’s the case. I remember teaching myself Adobe Illustrator, but the tools were a way to get to something else. You have to find your way first, and then you figure out how you do it.

![https //g.co/recover for help [1-866-719-1006]](https://newsquo.com/uploads/images/202506/image_430x256_684949454da3e.jpg)

![[PATREON EXCLUSIVE] The Power of No: How to Say It, Mean It, and Lead with It](https://tpgblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/just-say-no.jpg?#)