Maternal mental health needs more peer-reviewed research—not RFK’s journal ban

This week, JAMA Internal Medicine published the results of a large new study that tracked mothers’ health from 2016 to 2023. It found that maternal mental health declined significantly over the past seven years. The crisis we regularly write about in Two Truths, my best-selling Substack on women’s and maternal health, is now being reported in one of the world’s most respected medical journals. Which journals matter I read the story with interest—not just because I write about women’s health for a living, but because I still pay a little bit more attention when I see “JAMA” in a headline. When I started my career as a health journalist at Men’s Health magazine in 2011, we were quickly taught which medical journals mattered most. The New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM). The Lancet. JAMA. These were the powerhouses. When research appeared in one of them, it carried weight. It still does. The maternal mental health study published this week found, among other things, that in 2016, 1 in 20 mothers rated their mental health as “poor” or “fair.” In 2023, that figure rose to 1 in 12. The research underscored the need for immediate and robust interventions in mothers’ mental health. Not a niche issue The study wasn’t perfect; it was cross-sectional (meaning it examined women at different points versus following them over time) and it relied on self-reported health—a far from flawless strategy. Still, its presence in JAMA Internal Medicine signals what I know and what you know to be true: Maternal mental health is not a niche issue. It’s national. Urgent. Undeniable. As my friend and trusted source Dr. Catherine Birndorf, cofounder of the Motherhood Center, told The New York Times, “We all got much more isolated during COVID. I think coming out of it, people are still trying to figure out, Where are my supports?” The sad truth is that they’re still missing; we’re actively fighting for them over at Chamber of Mothers. “Corrupt vessels” But here’s the thing that really caught my attention in all of this: Earlier this week, Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. suggested potentially banning federal scientists from publishing in leading medical journals, calling The NEJM, The Lancet, and JAMA “corrupt vessels” of Big Pharma. He proposed creating government-run journals—ones that would “anoint” scientists with funding from the National Institutes of Health. It’s true: Leading medical journals do accept advertising and publish industry-funded studies. There is also a long history of criticism surrounding the influence of pharmaceutical companies in academic publishing. Kennedy’s concerns are not new. What’s also true is that these journals disclose their funding, have rigorous peer-review processes (where independent experts, usually leaders in a field, assess the research and flag concerns), and have low acceptance rates. They publish research that changes the way medicine is practiced globally, informs policy decisions, and protects patients, particularly women and mothers. (The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendations on breast cancer screening, which many clinicians follow, have been published and updated in JAMA; The Lancet regularly highlights maternal mortality disparities; The NEJM has published large-scale trials on critical women’s health issues, from cardiovascular disease to hormone replacement therapy.) Program terminated And here’s something else you need to know: Last week, I interviewed a leading physician and expert on gestational diabetes at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. She shared a statistic that surprised me (sometimes hard to do when I’ve been reporting on health for 15 years): Up to one-half of women who have gestational diabetes in pregnancy go on to develop type 2 diabetes within 5 to 10 years of giving birth. The landmark study that laid the groundwork for understanding diabetes prevention in high-risk groups, including women with a history of gestational diabetes? It was called the Diabetes Prevention Program, and it was first published in The NEJM in 2002. Recently, under Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s leadership—an administration that claims to be committed to “ending chronic illness”—that program was terminated. Holding institutions accountable I’m not a doctor, scientist, or researcher. I’m trained as a health reporter. And I trust that training—just as I trust the countless physicians and researchers I’ve interviewed over the years, many of whom have spent their careers trying to get their work published in the most rigorous medical journals out there. As a journalist, I believe in holding institutions, including medical journals, accountable—especially when it comes to conflicts of interest. That’s part of the job. But this administration has attempted to infuse a tremendous amount of chaos and confusion into a whole host of topics, health included. Health is nuanced. So is science. But let’

This week, JAMA Internal Medicine published the results of a large new study that tracked mothers’ health from 2016 to 2023. It found that maternal mental health declined significantly over the past seven years.

The crisis we regularly write about in Two Truths, my best-selling Substack on women’s and maternal health, is now being reported in one of the world’s most respected medical journals.

Which journals matter

I read the story with interest—not just because I write about women’s health for a living, but because I still pay a little bit more attention when I see “JAMA” in a headline. When I started my career as a health journalist at Men’s Health magazine in 2011, we were quickly taught which medical journals mattered most. The New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM). The Lancet. JAMA. These were the powerhouses. When research appeared in one of them, it carried weight. It still does.

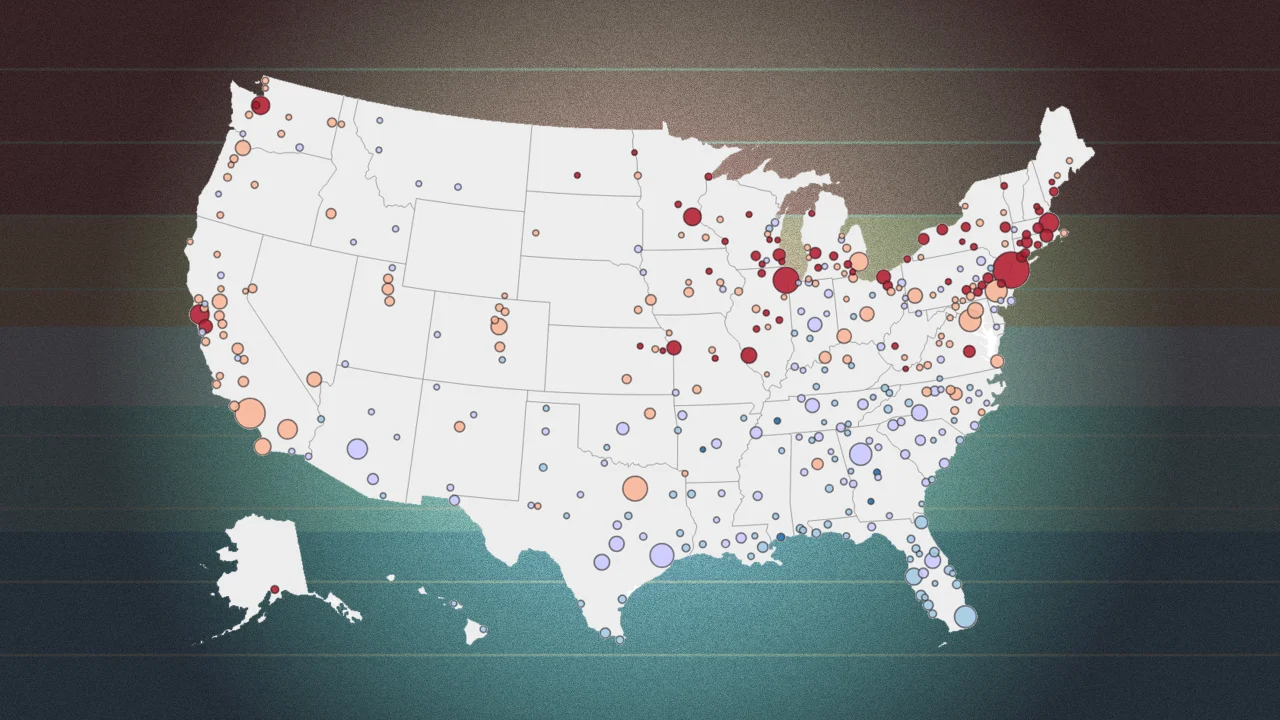

The maternal mental health study published this week found, among other things, that in 2016, 1 in 20 mothers rated their mental health as “poor” or “fair.” In 2023, that figure rose to 1 in 12. The research underscored the need for immediate and robust interventions in mothers’ mental health.

Not a niche issue

The study wasn’t perfect; it was cross-sectional (meaning it examined women at different points versus following them over time) and it relied on self-reported health—a far from flawless strategy. Still, its presence in JAMA Internal Medicine signals what I know and what you know to be true: Maternal mental health is not a niche issue. It’s national. Urgent. Undeniable.

As my friend and trusted source Dr. Catherine Birndorf, cofounder of the Motherhood Center, told The New York Times, “We all got much more isolated during COVID. I think coming out of it, people are still trying to figure out, Where are my supports?”

The sad truth is that they’re still missing; we’re actively fighting for them over at Chamber of Mothers.

“Corrupt vessels”

But here’s the thing that really caught my attention in all of this: Earlier this week, Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. suggested potentially banning federal scientists from publishing in leading medical journals, calling The NEJM, The Lancet, and JAMA “corrupt vessels” of Big Pharma. He proposed creating government-run journals—ones that would “anoint” scientists with funding from the National Institutes of Health.

It’s true: Leading medical journals do accept advertising and publish industry-funded studies. There is also a long history of criticism surrounding the influence of pharmaceutical companies in academic publishing. Kennedy’s concerns are not new.

What’s also true is that these journals disclose their funding, have rigorous peer-review processes (where independent experts, usually leaders in a field, assess the research and flag concerns), and have low acceptance rates. They publish research that changes the way medicine is practiced globally, informs policy decisions, and protects patients, particularly women and mothers. (The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendations on breast cancer screening, which many clinicians follow, have been published and updated in JAMA; The Lancet regularly highlights maternal mortality disparities; The NEJM has published large-scale trials on critical women’s health issues, from cardiovascular disease to hormone replacement therapy.)

Program terminated

And here’s something else you need to know: Last week, I interviewed a leading physician and expert on gestational diabetes at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. She shared a statistic that surprised me (sometimes hard to do when I’ve been reporting on health for 15 years): Up to one-half of women who have gestational diabetes in pregnancy go on to develop type 2 diabetes within 5 to 10 years of giving birth.

The landmark study that laid the groundwork for understanding diabetes prevention in high-risk groups, including women with a history of gestational diabetes? It was called the Diabetes Prevention Program, and it was first published in The NEJM in 2002. Recently, under Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s leadership—an administration that claims to be committed to “ending chronic illness”—that program was terminated.

Holding institutions accountable

I’m not a doctor, scientist, or researcher. I’m trained as a health reporter. And I trust that training—just as I trust the countless physicians and researchers I’ve interviewed over the years, many of whom have spent their careers trying to get their work published in the most rigorous medical journals out there.

As a journalist, I believe in holding institutions, including medical journals, accountable—especially when it comes to conflicts of interest. That’s part of the job. But this administration has attempted to infuse a tremendous amount of chaos and confusion into a whole host of topics, health included. Health is nuanced. So is science.

But let’s be clear: Suggesting that medical research be limited, controlled, or replaced by “in-house” publications is dangerous. Defunding evidence-based programs that serve high-risk groups, including mothers, is backward. Supporting high-quality, peer-reviewed research should be the bare minimum for anyone who cares about women’s health.

Canary in a coal mine

In their report, the authors of the new JAMA Internal Medicine study wrote, “Our findings are supportive of the claim made by some scholars that maternal mortality may be a canary in the coal mine for women’s health more broadly.”

It’s a statement that places maternal health where it belongs: at the center of women’s health.

As Dr. Tamar Gur, director of the Soter Women’s Health Research Program at Ohio State, told The New York Times, “Now I have something I can point to when I’m seeing a patient and say, ‘You’re not alone in this.’ This is happening nationally, and it’s a real problem.”

That’s the power of credible, peer-reviewed research. That’s where real change starts.