Create Mental Space to Be a Wiser Leader

Nathalie Lees In the face of alarming political polarization, environmental degradation, pressure to acquire the latest emerging technology, and unrelenting, divergent stakeholder expectations, these times call for leaders to engage in collective, thoughtful, and wise decision-making. But at a moment when leaders might see an opportunity to galvanize their teams to be at their most […]

Nathalie Lees

In the face of alarming political polarization, environmental degradation, pressure to acquire the latest emerging technology, and unrelenting, divergent stakeholder expectations, these times call for leaders to engage in collective, thoughtful, and wise decision-making. But at a moment when leaders might see an opportunity to galvanize their teams to be at their most skillful and collaborative, we’ve observed that they are instead, often unwittingly, doing the opposite.

With the pace of change often dictating the pace of business, the leaders trying to keep up with it may cling to what is known and keep their focus narrow to move as fast as possible — or they may be reactive and make hasty, ill-considered decisions.

Consider some of the data from our global survey of nearly 2,000 employees primarily at a middle to senior level in their organizations. Some 40% of them indicated that they had no time to reflect on how to plan and prioritize, 24% were too busy to speak about and reflect on failures, and 59% of them described their meetings as rushed. Under those circumstances, what is the likelihood that they were engaging in high-quality discussions and decision-making? What would the consequences of low engagement be?

Here’s the problem: The doing mode, as we label it in our research, has become an overplayed strength.1 In this mode, managers’ focus is narrowly on short-term, tangible targets for instrumental gain and predictable control. This is, of course, vital for both personal and business survival and performance; however, it can be disastrous as the dominant way of operating. Prioritizing doing in the form of rapidly executing an endless stream of tasks leads to a decline in psychological safety, fosters burnout, stifles innovation, lays a foundation for poor decision-making, and can undermine social capital by isolating people from one another.

What we call the spacious mode is a different, more expansive form of attention where people are able to consider interdependencies and perceive relationships. They dwell in the present moment to deepen their understanding of what is happening now rather than projecting themselves into the future or dwelling on the past. They leave space for possibilities and serendipity rather than staying anchored in the predictable. In the spacious mode, free from the immediate expectation of action, they are in a state of flow with the world around them rather than in a state of fixity, fragmentation, and separation.

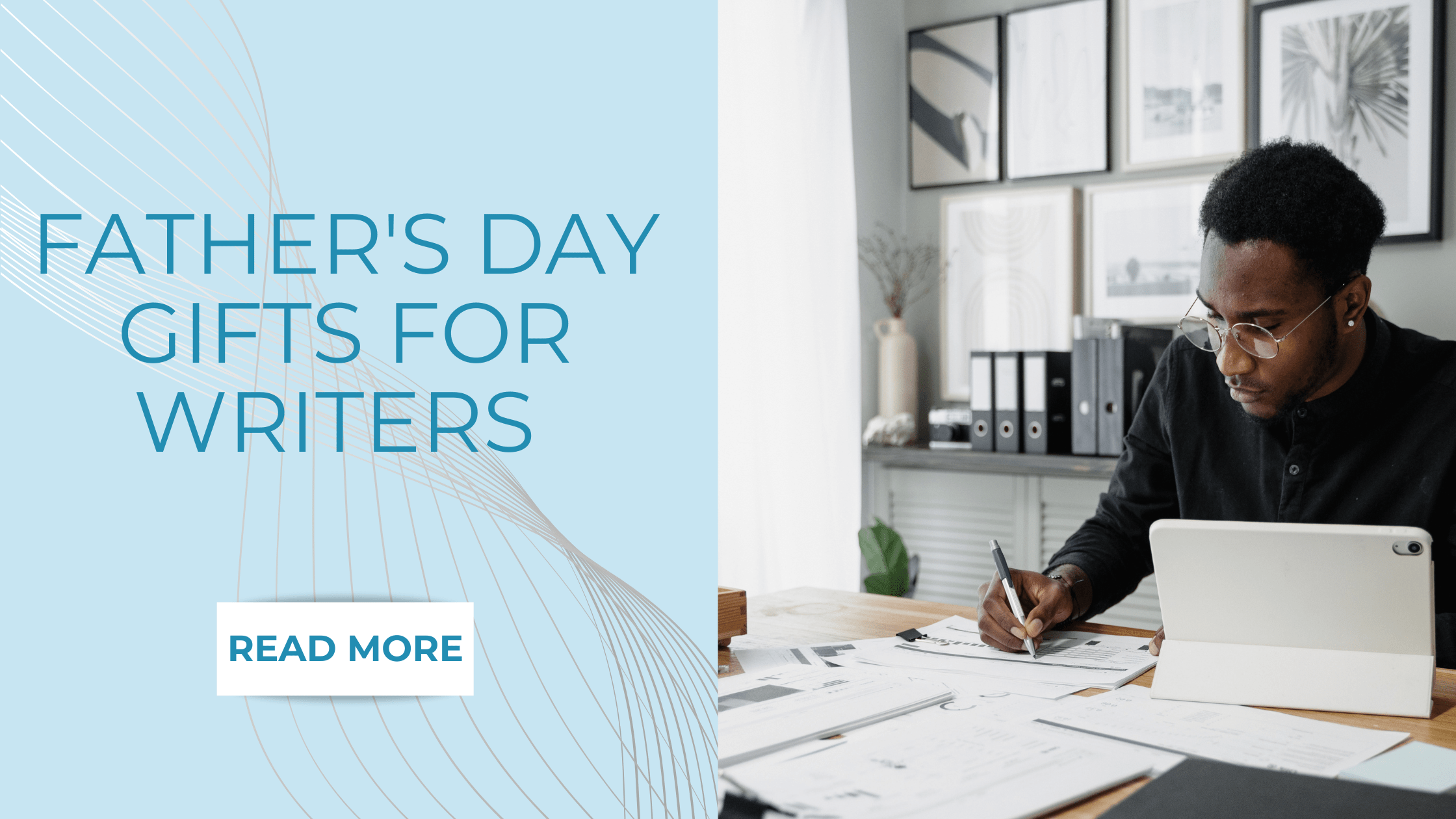

The image below illustrates this experientially. When you narrowly focus on it, it appears to be static. But when you widen your gaze, you experience the illusion of movement.

Being able to engage in both doing mode and spacious mode is important to people’s professional and personal lives. Much of people’s lives is spent in doing mode because it is critical for humans’ day-to-day survival. Developing the capacity for spacious attention at work in particular is foundational to improving the quality of the conversations you have, the meetings you attend, and the relationships you are part of, all of which are at the heart of personal and organizational performance.

If you are unable to access either mode, you are stuck — incapable of seeing your situation or moving forward to action. (See “The Attentional Mode Framework.”) If you rely heavily on the doing mode but lack spacious attention, you can become overwhelmed with busyness. Conversely, if you are strong at spacious mode but weak at doing mode, you risk adopting an impractical idealism, connected with the world but unable to act. When you have access to both modes, you can flourish — with your doing directed by a deep understanding of context, relationships, interdependencies, values, and perspective.

Our work seeks to address what our research participants see as their primary workplace challenge: how to move from busyness to flourishing. The difficulty is that when people allow themselves to be subsumed by the doing mode at work, they are so busy that they can’t even see, let alone access, the spacious mode. In the children’s literature classic Winnie-the-Pooh, A.A. Milne so wonderfully summarized the problem of having no time to reflect and how it keeps us locked into a particular way of knowing: “Here is Edward Bear, coming downstairs now, bump, bump, bump, on the back of his head, behind Christopher Robin. It is, as far as he knows, the only way of coming downstairs, but sometimes he feels that there really is another way, if only he could stop bumping for a moment and think of it.”

Pay Attention! What Mode Are You in Now?

People often read articles like this one in either a doing or a spacious mode that they rarely notice, let alone question. But we ask you to pay attention to both modes right now because this is central to our point.

Some classic habits of engaging with a long article in MIT Sloan Management Review are driven by the doing mode: skimming for the key messages and deciding swiftly whether you’re interested in the topic, searching for the business case, focusing on quantitative data, and jumping to the top tips to see which ones you can apply to your situation right now.

Are these habits present now, as you read this? (We acknowledge that if they are, you might not actually be reading this bit, as you’ve already skipped over it.)

It’s perfectly fine — sensible, in fact — to skim and search for compelling business cases and to-dos. However, we suggest that it’s a good idea to notice when you’re in that mode, specifically choose to be in it, and acknowledge the consequences. For example, some concepts defy quick understanding, are reliant on longer-term engagement, and are more usefully understood when an individual contemplates their own experience before, or even instead of, ingesting the framing and advice of experts.

But it is vital to be able to deliberately choose to engage in a more spacious mode, which might mean dedicating some uninterrupted time to read attentively, pausing to consider and reflect, dwelling with the ideas after reading to consider their implications, and perhaps inviting others into conversation on the topic.

How often do you do this? We’d like to invite you to engage with this article spaciously and explore how easy or difficult, how rewarding or frustrating, it is to pay attention in this way. This article, and our research, is in the service of assisting leaders of all types and at all levels in making the space for the wiser decision-making that they desperately need in their roles, by inviting them to pay attention to how they pay attention.

Before you read on, please consider the questions we started our research groups and interviews with. We deliberately began each conversation without predetermined or fixed definitions:

- When have you experienced a sense of spaciousness in life and at work?

- What were the qualities of that experience?

- How common and how important are those qualities?

Why Does Doing Mode Dominate Our Work Cultures?

A senior leader we met during our research was renowned in her organization for her catchphrase “be clear, be quick, be gone,” advice that she liberally doled out to all junior employees. Another research participant described the typical interaction with her bosses: “Managers will say: ‘Sorry, I’m 15 minutes late for the meeting [and] I do have to leave five minutes early. I know you’ve got to tell me stuff. Make this quick.’”

There is no doubt that on a daily basis, those in positions of power communicate explicitly or implicitly that there is little time or space to discuss complex, ambiguous issues that have no clear solution. They can be masterful at sucking the space out of the workplace.

Are you one of these leaders? It wouldn’t be surprising to us if you were. In all fields, C-suite leaders tend to have ever-shorter tenures, so they feel compelled to quickly demonstrate success.2 That gets translated into the need to urgently “do stuff” rather than take a more considered or longer-term perspective; after all, why focus on payoffs that you may not be around long enough to get credit for?

Leaders are both perpetuators and victims of too much of an emphasis on doing. There are structural conditions that impel this behavior, and those of us who comply with the need for speed are also active agents in reinforcing it. Judging much business leadership by the metrics of short-term shareholder value (and the unquestioned compulsion for growth) has certainly encouraged the constant push to be doing more — often, with fewer people.

Everyone, wherever they are positioned in the organizational hierarchy, has some capacity for agency, some responsibility for how they pay attention to the world, and the ability to draw on both spacious and doing modes. However, there is particular pressure on those in leadership positions: The more senior they are seen to be, the more that what they pay attention to will be noticed by others and treated as what is worthy of their attention as well. The priority for leaders is therefore to give themselves the space to take a few moments to step into the spacious mode before they agree to an agenda, go into a meeting, or send an email. That pause gives them time to consider what their implicit or explicit attention conveys about what is of value to the business.

The Leader’s Responsibility

One of us (Megan) attended the leadership conference of a global health care organization at the invitation of the CEO, whom we will call Kris. Kris was exasperated by the people on his senior leadership team, who persistently attended to day-to-day operations and rarely to the more strategic, innovative, and collaborative projects that he felt they needed to, given their roles. The issue, he felt, was one of time management and delegation.

Megan asked Kris about his frequent one-on-one meetings with his team. What did they discuss, and what did he put at the top of the agenda? It turned out that meetings always began with an examination of progress toward quarterly targets. This would often consume the entire meeting as issues and problems were debated and potential actions were discussed. Kris’s team could see where his priorities were in practice, and they followed his lead, always ensuring that they were on top of the operational details and treating less immediately tangible considerations around culture and strategy as a nice-to-have rather than a need-to-have.

Role-modeling the spacious mode can be challenging for leaders. Four traps, in particular, can suffocate it.

1. The superiority illusion. Our research over the past decade has clearly shown that most of us think that we’re better at listening than others perceive us to be.3 In addition, our recent research suggests that it’s also common for people to rate themselves more highly at accessing and holding the spacious mode than others would rate them. They may intend to be the wise and thoughtful leader who helps others feel seen, but intention isn’t enough; behaviors matter.

2. Advantage blindness. When people have titles and labels that convey status in a system, they may act counterculturally, unaware of the risks that others with less power face. A senior leader’s recommendation to start a dialogue about a particular issue may be respected more than if it were suggested by someone more junior. Advantage blindness means that someone doesn’t see their relative power and that they assume others can speak up, be heard, and raise the same issues that they can, with the same degree of confidence and impact. Sometimes this means that leaders wait for others to invite the spacious mode into a group discussion rather than taking responsibility to do so themselves.

3. Threats to image. Many leaders get promoted for being doers and work in organizations that prioritize action. Paul, one of our research participants, told us that he was in a very task-driven organization that recognizes task productivity in its rewards and in conferring status and power. He explained that it could be far too risky to pause from the predictable activity on a to-do list in order to pay attention to an issue with no obvious solution because he might be seen as negative, lazy, or impractical. Sam, another participant, expanded on Paul’s observation to express that it’s not only your image to others that is at risk but your own self-image as well: “For a long time, I truly, truly believed it was better to be busy. I would think, ‘That person is a thinker; I’m a doer,’ and I felt superiority that I was very action-orientated and was getting things done.”

4. Metric dominance. As Jerry Muller, a polymath and professor at the Catholic University of America, explained, “While we are bound to live in an age of measurement, we live in an age of mismeasurement, overmeasurement, misleading measurement, and counterproductive measurement.”4 The human desire to predict and control has led people to focus on the trackable and tangible. Intangible factors, such as trust, joy, and meaning, are considered nice-to-haves, if they’re thought about at all. Suggesting that someone should pay attention to phenomena for any other reason than addressing a direct business case can be career-limiting. Quarterly targets end up ruling conversations — and since they determine how leaders are measured, they consume a tremendous amount of leaders’ attention and dominate the conversational agenda.

Leaders seldom realize how their behaviors and reputation can limit others who see themselves as less powerful. They do this by establishing implicit rules about what matters — rules that usually favor the doing mode over the spacious mode. They may forget that they’re often in the spotlight and that every public gesture may be interpreted as significant. When they don’t consider the impact they could have on others’ attention and focus solely on tangible metrics, they constrict and undermine permission for others to access the vital spacious mode. Which one of these traps might you be at risk of falling into? Which might your colleagues say you’re already in?

Encouraging the Spacious Mode

To help leaders develop the capacity for the spacious mode in themselves and their organizations, we’ve devised the SPACE framework. SPACE is a mnemonic for remembering the five factors within leaders’ control that can encourage (but can’t impel) the spacious mode in their meetings and conversations.

- Safety: Feeling physically and mentally safe.

- People: Surrounding yourself with people who generate spaciousness.

- Attention: Learning to purposefully pay attention to what you pay attention to.

- Conflict: Encountering difference that jolts you out of autopilot “doing” behavior.

- Environment: Noticing how the external environment impacts your internal state and your relationships.

Safety. When people feel vulnerable or anxious, their focus narrows to self-protection. Their thinking tends to spiral into a vortex of vigilant scanning, and they can obsess over doing — taking the actions that might make them safe. Therefore, enabling psychological and physical safety is vital for leaders to set the conditions for spaciousness (and enables numerous other benefits).5

In our surveys of more than 13,000 global employees over the past 10 years, 42% said they felt that they had limited or no ability to challenge ways of working at their organization. This is indicative of a context where many people’s attention is restricted to self-preservation. If this is the case, it is unlikely that they feel able to invite the spacious mode into meetings and their conversations with colleagues.

What can you do to help others feel physically and psychologically safe to say what needs to be said and hear what needs to be heard? Attend to issues of physical access, confidentiality, and anonymity during virtual and in-person meetings and conversations, especially when attendees are likely to have such concerns. Critically examine agendas that govern meetings and other interactions to ensure that there’s space to discuss issues that are less measurable or task-focused, such as team and personal development, meaning, and creativity. Examine the landscape of your meetings to ensure that you’re creating the space for the wide range of conversations that are needed for the team to flourish; while some interactions home in on tasks, others make the spacious mode possible.

It’s inevitable that you or others will at some point make a mistake in a relationship or fail at a task. Ensure that your response is productive in such situations. Encourage reflection and learning, not defensive justification, especially in the case of intelligent failures — those that arise from necessary experimentation and provide valuable new knowledge.6 Notice and guard against common negative responses such as blaming and scapegoating. Notice whether people feel that they can speak freely and challenge you and one another, and whether they offer genuinely different, creative ideas. If they don’t, investigate the reasons for that and take steps that will enable people to show up in the spacious mode safely.

Acknowledge power differences, and never underestimate how your status can constrict the space for others to think, reflect, speak, and listen.7 For example, when the CFO at a global law firm showed up at an innovation session for his direct reports that we were facilitating, it was clear that he was oblivious to his impact on his team. The moment he arrived, they shrank away from their more expansive, challenging, and creative ideas, choosing to share only what was more traditionally and immediately actionable.

People. As people interact with others, they intimately affect one another. Everyone’s thoughts and feelings are shaped through their relationships, and their emotions are contagious. Some people invite a doing mode; others typically invite a more expansive one. Consider the people with whom you interact most regularly, in the workplace and more widely, both in person and virtually. What effect do they have on you, and you on them, when it comes to the modes of doing and spaciousness? Do others regard you as someone who gives them space or constricts it?

In order to engage in the spacious mode, have conversations with people who allow you to view the world from different perspectives and enable you to perceive how your habits of mind limit what you know and what you value. These partners may include coaches, facilitators, or therapists — people who contain your discomfort when you step out of your habitual, often busy, way of being. Try to cultivate relationships outside of your normal social and professional circles, and join teams and community groups, online and off, that encourage a sense of spaciousness. For example, Megan attends a #SpacesForListening group, where eight people, who often don’t know one another, meet for an hour to reflect, speak, and listen.8 This short pause is often experienced as profound.

To further develop your spaciousness-building skills, withdraw from settings that are constrictive, such as media and social media platforms that actively restrict perspectives by feeding you only what you want to hear or covering topics with which you’re already familiar. Recognize and reward people, formally and informally, for their capacity for spaciousness, and give feedback to those who constrain it. Gather feedback from people who are willing to thoughtfully share their genuine experiences regarding your impact on others’ attention.

Attention. Spaciousness is a matter of attention management, not time management. Developing the capacity to notice where your attention is and then moving it when necessary is a skill that can change your life and the lives of those around you. What do you pay the most and least attention to at work and at home? How does this show up in the way you behave and interact with others?

Attention is habitual and learned; surprisingly, although many of us train our bodies for physical health, most of us leave our minds up to chance. However, it is possible to train the mind in order to open a space between stimulus and response. Research Megan conducted showed how 10 minutes of daily mindfulness practice can allow people to pause, pay attention more expansively to context, and make different choices more of the time.9 Purposefully shifting attention to physical sensations or sounds can be enough to move someone from the doing mode to a more expansive awareness, especially if they’re trapped in rumination or anxious thoughts. Similarly, they can use an anchor activity as a reminder to pay attention differently. For example, they could use a cue, like unlocking the front door after a day at work, as a reminder to check their emotional state before engaging with their family.

Time management techniques can help people ensure that they have protected periods of time with minimal interruption. With discipline, they can use this time for more expansive attention and deep work — the ability to focus on a cognitively demanding task without distraction. A number of online groups are also emerging that enable people to “body double,” or work alongside someone as they work on their own task, which establishes a social contract that can help both parties stay focused on their intentions for a set period of time.

Set yourself a task of paying attention to what gets paid attention to. Choose a few upcoming meetings to deliberately notice whether conversations about tasks also allow space for more expansive conversations around topics such as interdependencies, team development, personal experiences, and creativity. In our survey of nearly 2,000 employees, 88% of respondents agreed that tasks were highly prioritized in day-to-day conversations, while only 37% and 53%, respectively, believed that creativity and learning were also seen as high priorities.

Pay attention to what gets measured. Metrics solely focused on short-term, tangible targets tend to guide people’s attention. Consider the impact of measurement and, if necessary, drop some metrics and introduce others that encourage the spacious mode. For example, you could reengage with the original intention of the balanced scorecard measurement tool — and its promotion of learning and development as the root of sustainable performance — alongside metrics that reflect the real customer experience.10

Conflict. Conflict occurs when someone’s mental model — their map of how they think about and know the world — conflicts with their lived experience. While conflict is often associated with relationship disputes, it also arises during experiences in which people encounter dissonance that jolts them into inquiry and consideration of a wider perspective. Who and what challenges the way you understand the world and invites you to broaden your attention?

To prompt productive conflict, ensure that you and others are exposed to experiences outside of what is usual to you. This might include taking a sabbatical to study something outside your area of professional expertise, or attending conferences whose speakers you disagree with. You might spend time on “management by walking around” to hear about employees’ experiences across the hierarchy (rather than share your own perspective). Additionally, during stakeholder visits, you could direct your attention to how their priorities and agendas differ from yours and allow crucial time and support for reflection afterward. Don’t short-circuit such encounters by relying on pulse surveys and written reports, which often reflect a superficial and intellectual understanding of someone else’s experience rather than a rich and emotional one. Conflict needs to be an emotional encounter with difference, not just a cognitive one, if it is to leave a lasting impact and jolt you into noticing how your way of being limits your understanding.

Notice how many clarification-seeking questions people ask and how often doubts are voiced about what’s being proposed in meetings. How often do people raise red flags, insisting that what’s being nodded through needs to be debated or considered from a different angle? Rumor has it that Alfred Sloan, CEO of General Motors in the early 1940s, asked in a board meeting, “I trust we are all in agreement?” When everyone nodded, he reportedly said, “Then I suggest that we end the meeting and reconvene in two weeks, to give ourselves time to generate some constructive disagreement.”11 Groupthink is a habit into which humans are constantly falling, and no one is immune. Employ more creative methods for challenging narrow perspectives of a particular issue, such as Lego Serious Play, improvisation, art, or forum theater — a technique that invites people to step into different roles and scenarios and experiment with alternative behaviors. These approaches need to be embedded into the day-to-day activities of the organization rather than set aside as entertainment at a team offsite meeting.

Pay attention to perspectives from new team members. Although their differences are often why they were recruited into an organization in the first place, they are frequently silenced and feel pressured to quickly assimilate into existing cultural norms of thought and behavior. The responsibility for encouraging difference rests more with the wider group than with the new recruit. Established group members can actively sponsor new members and encourage and highlight the implications of their insights. Ask, “What is it that we are finding hard to hear from this new person? And what work do we need to do on ourselves so we can make it safe for this voice of difference to be heard?”

Environment. When asked to recall an experience of spaciousness, most people who participated in our research mentioned the physical environment they were in. The external world has an astounding impact on what people pay attention to and how; exposure to nature, for example, often stimulates the spacious mode. This should be unsurprising, given that humans are embodied beings constantly shaped and influenced by their senses — a fact often forgotten in a business world that spends so much time ignoring the body and insists on the world being understood cognitively. How does the physical environment where you work affect how you feel and think? Which environments help you focus well on doing mode and which invite you to be more spacious?

To encourage the spacious mode, be creative in where you work and meet. When possible, have walking one-on-one meetings, whether you’re together or on the phone. Rather than always meeting in the office or at your desk, shift to a coffee shop. Carefully consider the venue of the next offsite — not just in terms of costs and distance but also the environment it offers and how that could affect the work that gets done. Out of nearly 2,000 survey respondents, half thought that meeting organizers failed to pay thoughtful attention to when and where meetings were conducted. There’s an opportunity here to involve others in supporting inclusive, safe, expansive, welcoming, and creative spaces where factors like accessibility, noise, and light levels have been considered.

On an individual level, you can try punctuating your working day with a change in environment. Step outside or spend just a few minutes looking out the window with the intention of disrupting the doing mode and widening your gaze and perspective. Finding the spacious mode in the midst of workplace busyness can involve small, personal, unobtrusive actions in addition to the more public and structural ones.

Leadership as the Practice of Influencing Attention

To lead well, leaders must understand that their people differ in what they pay attention to and how they pay attention, and that those differences have significant consequences. Leaders must then notice when the doing mode has taken over and find a way to credibly explain the consequence to others. And finally, they must take the necessary steps for themselves and others to engage in spacious mode.

In her book How to Do Nothing, Jenny Odell writes, “We live in complex times that demand complex thoughts and conversations — and those, in turn, demand the very time and space that is nowhere to be found.”12 We agree and contend that allowing yourself and those around you to become busy fools is poor leadership. Conversely, it is an act of leadership to open and hold the spaces where, amid uncertainty and rapid change, vital, thoughtful, creative, and grounding conversations can be held.

In advocating the need for greater attention to the spacious mode, we are not undermining the vital work of the doing mode. The challenge from both personal and leadership perspectives is to find ways to integrate the two and become bilingual in these equally essential modes of attention.

![https //g.co/recover for help [1-866-719-1006]](https://newsquo.com/uploads/images/202506/image_430x256_684949454da3e.jpg)

![[PATREON EXCLUSIVE] The Power of No: How to Say It, Mean It, and Lead with It](https://tpgblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/just-say-no.jpg?#)