This renowned climate scientist says this is the most difficult time for climate science he’s ever seen

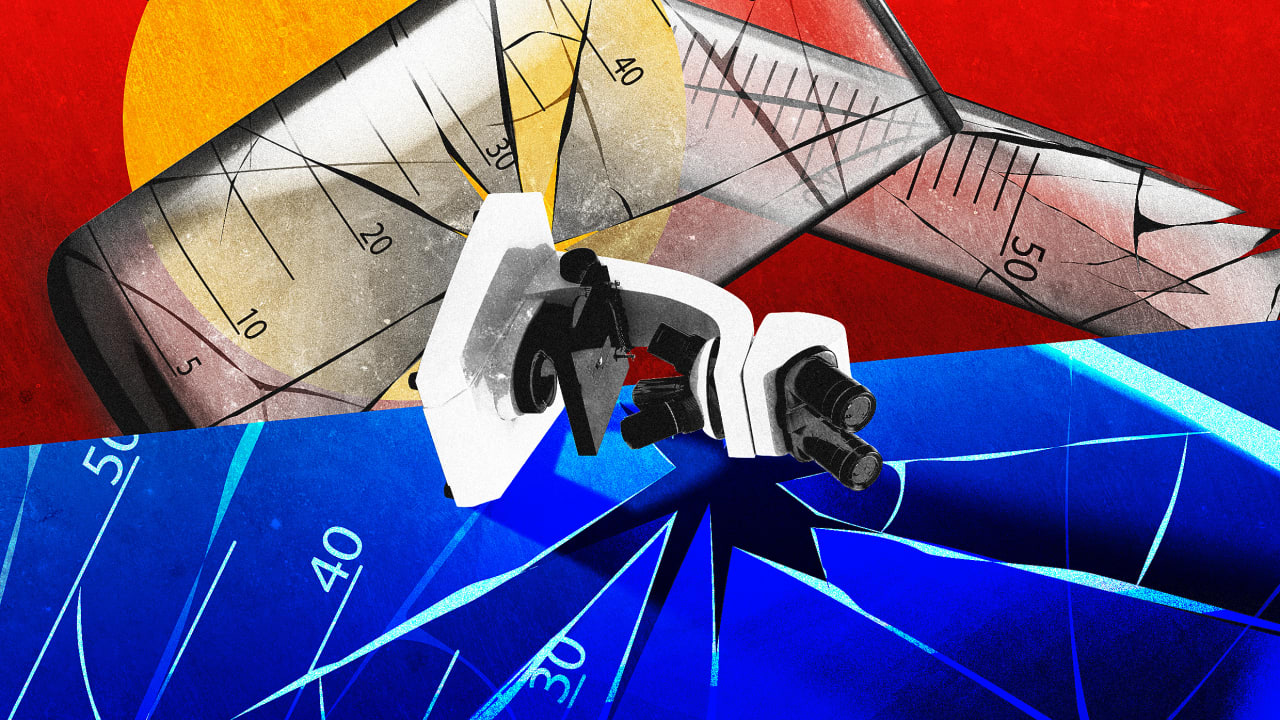

In 1995, Benjamin Santer was the lead author on a chapter of the second Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) that would alter climate science forever. In a culmination of more than a year of meticulous research, the chapter came to a groundbreaking conclusion—confirming an international scientific consensus that humans were having a discernible impact on the climate. The pushback was immediate and immense. Lobbyist groups erroneously accused Santer of removing discussion of scientific uncertainty in the report. Frederick Seitz, former president of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences and a founding member of the environmental skeptic conservative think tank the George C. Marshall Institute, published an opinion piece in The Wall Street Journal claiming, “I have never witnessed a more disturbing corruption of the peer-review process.” Despite being backed up by the climate science community, Santer underwent congressional hearings, personal threats, and calls for his dismissal at his lab. Despite the pushback, Santer has continued to do groundbreaking research identifying human fingerprints in many different observed climate variables and received a number of awards for his work, including a MacArthur Fellowship in 1998. Santer recently spoke to Fast Company about the threats the second Trump administration poses to the future of climate science and shared advice for the next generation of scientists entering a contentious time. (This interview has been edited for length and clarity.) How does the current state of climate research compare to other peaks and valleys you have seen over your career? I think this is the deepest valley that I’ve ever been in in my entire scientific career. It feels different from anything else that I’ve encountered, and I encountered some pretty deep valleys after publication of the discernible human influence finding in the 1995 IPCC report. But this is different because it’s so targeted. The intent of the administration is to destroy, to tear down a capability to do basic science, to understand how and why the world around us is changing, to understand the inequities of climate change, to invest in low-carbon energy sources and support the development of low-carbon energy. All of these things have happened in the first 100 days of the Trump administration, and so much destruction has impacted not only our long-term futures—in academia, in research, the grants that will be available for us, the opportunities at university—but also the leadership of this country and science and technology. And of course, not only in climate science and green energy, but also increasingly in health, the development of novel vaccines, the development of cancer drugs, all of that is imperiled. To turn away from those challenges as this administration is doing makes no sense whatsoever. What are some of the concrete steps this administration is taking to reduce climate protections? It’s been a full-court press, I would say: not only the illegal termination of probationary employees, tens of thousands of them across agencies like NOAA [National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration], EPA [Environmental Protection Agency], and NASA, but the changing of language [around climate change]. This willful ignorance seems very reminiscent of COVID under the first Trump administration. You may recall that President Trump argued that COVID was no worse than the seasonal flu. He seemed intent on downplaying any danger to the U.S. public that might interfere with the economy. Why do I mention that? Because it’s the same deal with climate change. If you pretend it doesn’t exist, then you can go on with business as usual, “Drill baby, drill,” all that kind of stuff. And that’s what’s happening. The administration is pretending that human-caused climate change isn’t happening, and everything’s fine, when it isn’t. In addition to the firings, in addition to the censorship, again—as has been widely reported—access to data is reducing. [For example,] because of some of the firings at NOAA, there aren’t scientists to launch weather balloons. At a number of locations, weather balloons are critically important. They make measurements of temperature and moisture, and those measurements are ingested by weather forecast models. They help the weather forecast models to know something about the current state of the atmosphere and the surface of the ocean, and that information is extremely important in making a reliable weather forecast. Because of the firings, we’re losing some of the weather balloon information that flows into weather forecasts. So all of this taken together, when you take a step back and look at it, is an effort to keep the public ignorant about the reality and seriousness of climate change. Do you think that there’s any possibility that other countries might be able to step in to fill the gaps the U.S. is creating? I hope that there are

In 1995, Benjamin Santer was the lead author on a chapter of the second Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) that would alter climate science forever. In a culmination of more than a year of meticulous research, the chapter came to a groundbreaking conclusion—confirming an international scientific consensus that humans were having a discernible impact on the climate.

The pushback was immediate and immense. Lobbyist groups erroneously accused Santer of removing discussion of scientific uncertainty in the report. Frederick Seitz, former president of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences and a founding member of the environmental skeptic conservative think tank the George C. Marshall Institute, published an opinion piece in The Wall Street Journal claiming, “I have never witnessed a more disturbing corruption of the peer-review process.” Despite being backed up by the climate science community, Santer underwent congressional hearings, personal threats, and calls for his dismissal at his lab.

Despite the pushback, Santer has continued to do groundbreaking research identifying human fingerprints in many different observed climate variables and received a number of awards for his work, including a MacArthur Fellowship in 1998.

Santer recently spoke to Fast Company about the threats the second Trump administration poses to the future of climate science and shared advice for the next generation of scientists entering a contentious time. (This interview has been edited for length and clarity.)

How does the current state of climate research compare to other peaks and valleys you have seen over your career?

I think this is the deepest valley that I’ve ever been in in my entire scientific career. It feels different from anything else that I’ve encountered, and I encountered some pretty deep valleys after publication of the discernible human influence finding in the 1995 IPCC report. But this is different because it’s so targeted.

The intent of the administration is to destroy, to tear down a capability to do basic science, to understand how and why the world around us is changing, to understand the inequities of climate change, to invest in low-carbon energy sources and support the development of low-carbon energy.

All of these things have happened in the first 100 days of the Trump administration, and so much destruction has impacted not only our long-term futures—in academia, in research, the grants that will be available for us, the opportunities at university—but also the leadership of this country and science and technology.

And of course, not only in climate science and green energy, but also increasingly in health, the development of novel vaccines, the development of cancer drugs, all of that is imperiled. To turn away from those challenges as this administration is doing makes no sense whatsoever.

What are some of the concrete steps this administration is taking to reduce climate protections?

It’s been a full-court press, I would say: not only the illegal termination of probationary employees, tens of thousands of them across agencies like NOAA [National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration], EPA [Environmental Protection Agency], and NASA, but the changing of language [around climate change].

This willful ignorance seems very reminiscent of COVID under the first Trump administration. You may recall that President Trump argued that COVID was no worse than the seasonal flu. He seemed intent on downplaying any danger to the U.S. public that might interfere with the economy.

Why do I mention that? Because it’s the same deal with climate change. If you pretend it doesn’t exist, then you can go on with business as usual, “Drill baby, drill,” all that kind of stuff. And that’s what’s happening. The administration is pretending that human-caused climate change isn’t happening, and everything’s fine, when it isn’t.

In addition to the firings, in addition to the censorship, again—as has been widely reported—access to data is reducing. [For example,] because of some of the firings at NOAA, there aren’t scientists to launch weather balloons. At a number of locations, weather balloons are critically important. They make measurements of temperature and moisture, and those measurements are ingested by weather forecast models.

They help the weather forecast models to know something about the current state of the atmosphere and the surface of the ocean, and that information is extremely important in making a reliable weather forecast. Because of the firings, we’re losing some of the weather balloon information that flows into weather forecasts.

So all of this taken together, when you take a step back and look at it, is an effort to keep the public ignorant about the reality and seriousness of climate change.

Do you think that there’s any possibility that other countries might be able to step in to fill the gaps the U.S. is creating?

I hope that there are folks in space agencies like the European Space Agency, the Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt (German Aerospace Center), and in Japan and China, who understand the seriousness of the threat to the continuity of these records. These aren’t records that just the U.S. uses.

The entire world uses these estimates of global-scale changes in the atmosphere, the ocean, the land surface for evaluating climate models, for doing fingerprint research, for improving our basic understanding of the atmospheric and ocean general circulation. And the U.S. has been a leader in this Earth observation enterprise and in making these datasets available to the international community. Now all of that work is imperiled, so the hope is that there are indeed folks who are contingency-planning in other countries who are trying to figure out, well, what do we do?

But if these satellites go away, the unfortunate thing is that it takes time, right? You can’t just launch a satellite and do this gap-filling very quickly. The development of new satellites and the launching of new satellites is the stuff of years, not the stuff of months.

It also would mean a huge financial investment in gap-filling, in the ocean, and in the satellite measurements of temperature, moisture, winds, you name it. So it is concerning. Hopefully there are those in Congress who will push back against the president’s budget request for NASA and will recognize that if the U.S hands off the baton of leadership in Earth observation to other countries, it will be difficult to flip a switch and restart.

In part because they will lose hundreds, perhaps thousands of good people who have no prospect of employment given what’s happened with NSF [National Science Foundation] grants and firings and cuts to NOAA and NASA. If you lose that expertise, then even with a change of the administration, it’s difficult to restart.

This is why it’s so critically important for folks to use their voices and speak publicly about the harms caused by this willful ignorance, and I’m going to try continuing to do that as long as I possibly can. Scientists don’t have the hippocratic oath that doctors do, but we should. If you see that harm to the stability of climate and to present and future generations is being caused, then, in my opinion, you have a moral and ethical responsibility as a climate scientist to speak out against that.

Do you have any advice for young people looking to get into the sustainability world in this tumultuous time?

Keep plugging away. If you’re passionate about the science, if it’s part of your identity, find a way to do it. I can’t imagine not doing research. It’s part of who I am. It’s part of what I think about when I get up in the morning.

For anyone who is really concerned about the kind of world in which they and their loved ones will grow up, find a way of continuing to [work on climate research and advocacy], even if it’s only in your spare time and you have to have a different day job.

Science has to find a way of continuing. It’s a harsh world out there now with a lot of powerful people wanting to fundamentally change the scientific enterprise in the United States and remove consideration of inequities in our society causing unequal impacts of climate change. Science has to find a way of continuing, of living, of tackling the big questions of the day, irrespective of whether the administration likes or does not like the answer.

![https //g.co/recover for help [1-866-719-1006]](https://newsquo.com/uploads/images/202506/image_430x256_684949454da3e.jpg)