This stratospheric airship is 65,000 feet above Earth and investigating which gas companies are leaking methane

Inside an airplane hangar in Roswell, New Mexico, a massive blimp-like airship—214 feet long—is getting ready to float into the stratosphere. Built by a startup called Sceye (pronounced “sky”), the helium-filled aircraft is designed to gather information that satellites miss. In its next flight, in July, it will hover over New Mexico sending back real-time data about pollution from the state’s hundreds of oil and gas producers. It can report not only that there’s a plume of methane pollution in the air, but that a particular gas tank from a particular company is leaking a specific amount of the potent greenhouse gas each hour. “We can see the specific emitter and the rate of emissions in real time,” says Mikkel Vestergaard Frandsen, Sceye’s CEO. “And that’s entirely new.” [Photo: Sceye] How a social entrepreneur started working with NASA tech Frandsen, a Danish social entrepreneur, is known for transforming Vestergaard, his family’s textile business, into a company focused on humanitarian innovation. (The company makes mosquito nets to help fight malaria, for example, and a spinoff called LifeStraw makes water purification tech.) Because of his work, Frandsen was invited to be part of an effort to discover how tech from NASA could be used to help improve life on Earth. That’s how he learned about HAPS, or “high-altitude platform systems,” the technology that now underlies Sceye’s work. HAPS are designed to go to the edge of space, around 65,000 feet above the surface of the Earth. “You’re twice as high as air traffic, you’re above the jet stream, you’re 95–97% through the atmosphere,” Frandsen says. “So you can look up with great accuracy at stars, study black holes, look at asteroids. They were promoting this as a platform for science. I was reading this and thinking, sure, but you can also look down. You can have an entirely new way of addressing ocean conservation, or human trafficking, or last-mile connectivity, or methane monitoring, or early wildfire detection.” The concept for a HAPS airship wasn’t new. “It turned out the U.S. government had already spent billions trying to build this ‘stratospheric airship’ because staying below orbital altitude was considered sort of the holy grail of aviation,” he says. He started looking into why past efforts in the 1990s and early 2000s hadn’t worked, and realized that some factors had changed. New materials like graphene, for example, could help significantly reduce the weight of the airship and the batteries onboard. [Photo: Sceye] A decade of R&D Sceye, which was founded in 2014 and is based in New Mexico, took an iterative approach to its R&D. “I learned from studying those previous attempts that government funding often incentivizes you to go straight to prototype build,” he says. “You don’t have that iterative learning that tells you if you fail, why did you fail? Or if you succeed, why did you succeed? In every case, it didn’t succeed, and they didn’t really get their arms around the ‘why.’ So it all stranded there.” In 2026, the startup tested a nine-foot version of the device. A year later, that scaled up to 70 feet. The prototypes kept growing and flying higher. By 2021, the team succeeded in reaching the stratosphere. In 2022, they started doing demonstration flights. A year ago, the company successfully showed that the airship could operate through day and night. In the day, it runs on solar power; at night, it’s powered by batteries. The company also raised a Series C round of funding in 2024, which Pitchbook estimates totalling $130 million. (Sceye declined to confirm fundraising numbers, but said that it was valued at $525 million before the Series C round.) This year, the company plans to use its flights to demonstrate that the tech can hover in place for extended periods of time. Eventually, the team aims to be able to keep the HAPS in position for as long as 365 days. The 2025 flights will also demonstrate some of the uses of the tech. The company plans to deploy its platform in several ways; the next flight will also test the ability to track wildfires, for example. But it’s particularly well suited for tracking methane emissions. [Photo: Sceye] A powerful tool for tracking methane Methane is potent greenhouse gas. Over the short term, it’s more than 80 times more powerful than CO2 at heating up the planet. Methane emissions are also surging; leaks from fossil fuel production are a major source of the pollution. New Mexico, which is part of the Permian Basin boom in oil and gas, adopted a methane waste rule in 2021 to try to tackle the problem. By the end of next year, producers will have to achieve a 98% capture rate for methane. “We are looking at how we can make sure that gas is kept in the pipe and goes to its intended market instead of being released into the atmosphere,” says Michelle Miano, environmental protection division director at the New Mexico Environment Department. The state star

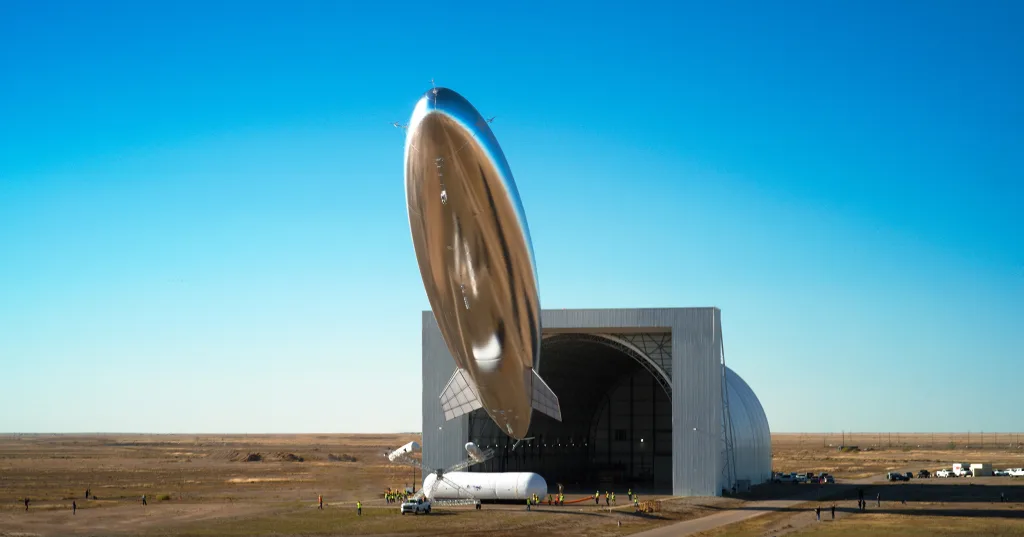

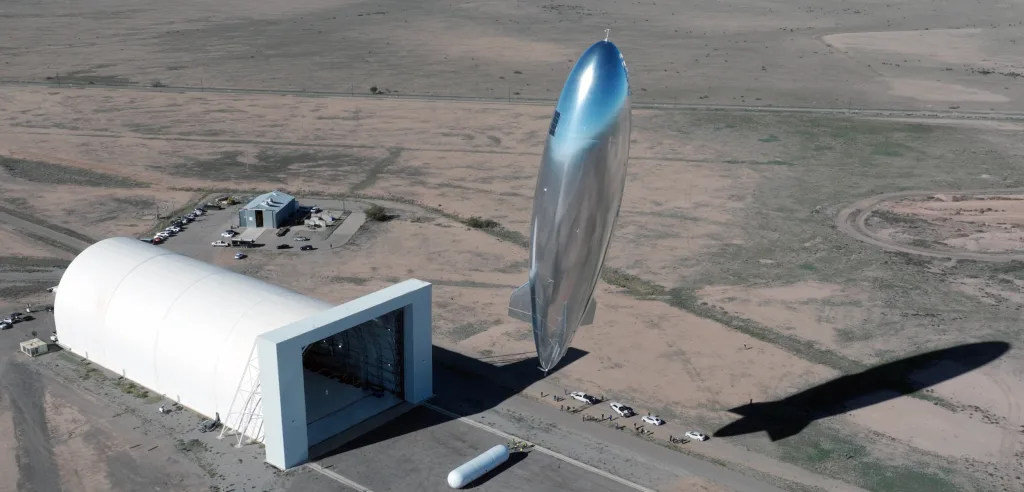

Inside an airplane hangar in Roswell, New Mexico, a massive blimp-like airship—214 feet long—is getting ready to float into the stratosphere.

Built by a startup called Sceye (pronounced “sky”), the helium-filled aircraft is designed to gather information that satellites miss. In its next flight, in July, it will hover over New Mexico sending back real-time data about pollution from the state’s hundreds of oil and gas producers. It can report not only that there’s a plume of methane pollution in the air, but that a particular gas tank from a particular company is leaking a specific amount of the potent greenhouse gas each hour.

“We can see the specific emitter and the rate of emissions in real time,” says Mikkel Vestergaard Frandsen, Sceye’s CEO. “And that’s entirely new.”

How a social entrepreneur started working with NASA tech

Frandsen, a Danish social entrepreneur, is known for transforming Vestergaard, his family’s textile business, into a company focused on humanitarian innovation. (The company makes mosquito nets to help fight malaria, for example, and a spinoff called LifeStraw makes water purification tech.) Because of his work, Frandsen was invited to be part of an effort to discover how tech from NASA could be used to help improve life on Earth. That’s how he learned about HAPS, or “high-altitude platform systems,” the technology that now underlies Sceye’s work.

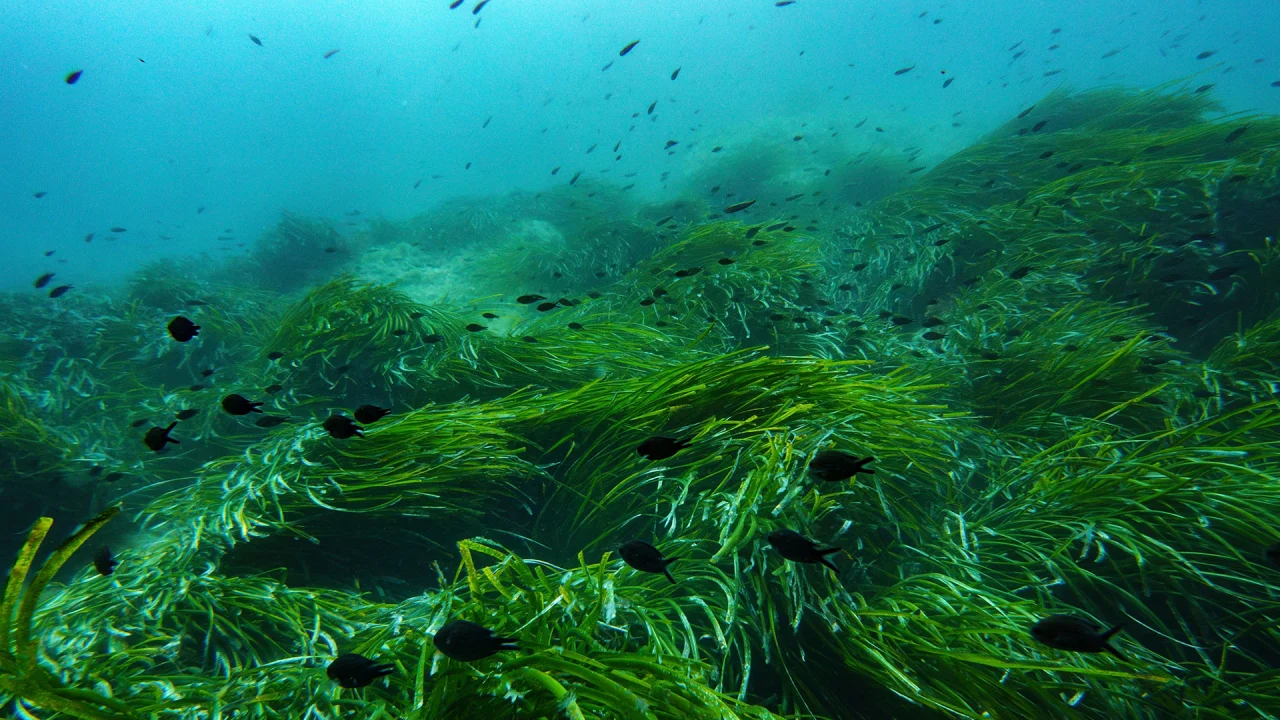

HAPS are designed to go to the edge of space, around 65,000 feet above the surface of the Earth. “You’re twice as high as air traffic, you’re above the jet stream, you’re 95–97% through the atmosphere,” Frandsen says. “So you can look up with great accuracy at stars, study black holes, look at asteroids. They were promoting this as a platform for science. I was reading this and thinking, sure, but you can also look down. You can have an entirely new way of addressing ocean conservation, or human trafficking, or last-mile connectivity, or methane monitoring, or early wildfire detection.”

The concept for a HAPS airship wasn’t new. “It turned out the U.S. government had already spent billions trying to build this ‘stratospheric airship’ because staying below orbital altitude was considered sort of the holy grail of aviation,” he says. He started looking into why past efforts in the 1990s and early 2000s hadn’t worked, and realized that some factors had changed. New materials like graphene, for example, could help significantly reduce the weight of the airship and the batteries onboard.

A decade of R&D

Sceye, which was founded in 2014 and is based in New Mexico, took an iterative approach to its R&D. “I learned from studying those previous attempts that government funding often incentivizes you to go straight to prototype build,” he says. “You don’t have that iterative learning that tells you if you fail, why did you fail? Or if you succeed, why did you succeed? In every case, it didn’t succeed, and they didn’t really get their arms around the ‘why.’ So it all stranded there.”

In 2026, the startup tested a nine-foot version of the device. A year later, that scaled up to 70 feet. The prototypes kept growing and flying higher. By 2021, the team succeeded in reaching the stratosphere. In 2022, they started doing demonstration flights. A year ago, the company successfully showed that the airship could operate through day and night. In the day, it runs on solar power; at night, it’s powered by batteries. The company also raised a Series C round of funding in 2024, which Pitchbook estimates totalling $130 million. (Sceye declined to confirm fundraising numbers, but said that it was valued at $525 million before the Series C round.)

This year, the company plans to use its flights to demonstrate that the tech can hover in place for extended periods of time. Eventually, the team aims to be able to keep the HAPS in position for as long as 365 days. The 2025 flights will also demonstrate some of the uses of the tech. The company plans to deploy its platform in several ways; the next flight will also test the ability to track wildfires, for example. But it’s particularly well suited for tracking methane emissions.

A powerful tool for tracking methane

Methane is potent greenhouse gas. Over the short term, it’s more than 80 times more powerful than CO2 at heating up the planet. Methane emissions are also surging; leaks from fossil fuel production are a major source of the pollution. New Mexico, which is part of the Permian Basin boom in oil and gas, adopted a methane waste rule in 2021 to try to tackle the problem. By the end of next year, producers will have to achieve a 98% capture rate for methane.

“We are looking at how we can make sure that gas is kept in the pipe and goes to its intended market instead of being released into the atmosphere,” says Michelle Miano, environmental protection division director at the New Mexico Environment Department. The state started working with Sceye in 2021, in a partnership with the EPA.

Right now, much of the data about emissions comes directly from companies themselves; that obviously makes it difficult for the state to confirm accuracy. Satellite data can also help track methane emissions, but not in the same granular detail.

“From space, it takes a lot of time in order to crunch that data and trace it back and figure out who exactly is the emitter in a certain region,” says Miano. “With technology that’s closer to the ground, there is the ability to get closer to some of the facilities to understand more specifically where they might be coming from.”

Because the Sceye airship is designed to stay in one position, it can continuously monitor emissions over hundreds of square miles in a region. Infrared sensors monitor methane emissions, while cameras take detailed photographs that can be overlaid with that data. The system means that it’s possible to spot leaks that a satellite can miss because it only passes over an area temporarily.

Satellites also don’t have the same resolution. The European Space Agency’s Sentinel-5, for example, sees methane in pixels that each represent seven square kilometers; the HAPS can get as close as one meter. (Sceye says that its approach is also more cost-effective than some other methods, including sensors on the ground that are slow to install, and planes or drones that have high hourly rates and can only take snapshots.)

“If we work with an oil company, we can say, ‘Hey, well number 62 has been leaking 68 kilos of methane per hour for the last 12 minutes,” Frandsen says. The company is now negotiating contracts with some fossil fuel companies, and planning to begin demonstration flights for them this year and commercial contracts next year.

In a test flight over New Mexico last year, the team identified a “super emitter” in Texas that was pumping an estimated 1,000 kilograms of methane an hour into the air—the equivalent of the hourly emissions from 210,000 cars.

When Sceye shared that data with the EPA last year, it’s not clear if the agency sent a warning letter to the polluter. Now, the Trump-era EPA is pulling back on enforcement. Congress also voted to stop the EPA from implementing a tax on excess methane emissions. But the New Mexico state government plans to continue doing as much as it can to fight pollution. Sceye’s data could help it work more efficiently.

“We are looking at how to increase funding for our agencies so that we are able to utilize technologies technologies that are coming online up and beyond standard reporting and standard on-the-ground inspections,” Miano says. “Because we have a limited staff, there are new ways that we need to continue looking at facilities with compliance issues to make sure that we can address as much as possible.”