When your town becomes a Nike brand

Earlier this month, Nike dropped the “Flagstaff” colorway of its Book 1 sneaker, the signature model of Phoenix Suns star Devin Booker. Its dark green shade reflects Flagstaff, Arizona’s situation in the world’s largest ponderosa pine forest—it’s not all cactuses and sand in the Grand Canyon State—and the shoe plays off Booker’s status as one of the many second-home owners in the area. “When Book needs to escape the desert heat,” the Nike copy explains, “he heads to Flagstaff, where he can walk the mountain paths worry-free.” Nike’s use of local color seems to be part of a larger branding trend that emphasizes small-scale authenticity over brute-force bigness. As a longtime Flagstaffer, I’m torn by this product. On the one hand, it brings a sense of validation: Nike has acknowledged us! We are seen! On the other, though, the use of the city’s good name to sell sneakers feels like something akin to appropriation, which is made more irksome when Nike doesn’t quite get the details right, as when it says the Book 1 “comes complete with a Humphrey’s Peak woven label, which pays homage to the highest point in Flagstaff.” (Actually, it’s the highest point in all of Arizona!) [Photo: Nike] And the heel of the shoe is adorned with the words, “No Service,” which, yes, is supposed to suggest that Flagstaff is a place to get away from it all, but also implies that it’s a sleepy backwater. Hey, my cell reception is great, thank you very much, and Flagstaff even got an In-N-Out Burger last year. It’s not exactly the Old West anymore, although, admittedly, an occasional tumbleweed does roll down the street, and a $300,000 shipment of special edition Air Jordans recently fell victim to a local train robbery. [Photo: Nike] Nike is undoubtedly unconcerned with my thoughts on its use of the Flagstaff name; like the thousands of other companies assigning place names to their products, it’s just trying to take advantage of a bit of the cachet that those names can deliver free of charge. City names, unlike personal names, are generally fair game for marketers; while you would be legally prohibited from calling your new vape product the “Timothée Chalamet Tank” or the “Peso Pluma Pen,” you’re welcome to name it after Tulsa or Poughkeepsie. Or perhaps you’d rather pick a more appealing city name with which to pair your product; something unique, as with the Hyundai Tucson, or evocative, à la Philadelphia Cream Cheese (which was created in New York!), or exotic, like the Jeep Grand Cherokee Laredo. Digging into data from the United States Patent and Trademark Office and the Census Bureau can give us a better idea of what those might be. By counting the number of trademark applications containing the names of the largest 100 U.S. cities by companies that are not located in those places, and adjusting for the population of each city, a measure of local trademark popularity can be calculated. [Photo: Nike] The three cities that come out on top of this list—Buffalo, New York; Madison, Wisconsin; and Lincoln, Nebraska—should probably be given asterisks, as most of the trademarks containing their names were probably not inspired by the cities themselves. This leaves Miami as the leader, with 357 outsider trademarks per 100,000 residents, followed by Boston (345). Next come Washington, D.C. (322) and Aurora, Colorado (311), although, like Buffalo, these two should perhaps be disqualified. Detroit (209), Chesapeake, Virginia (200), Atlanta (186), Phoenix (177), and New Orleans (164) are close behind. That such famous places would inspire the names of trademarks is not surprising, but expanding this analysis beyond the top 100 cities reveals the appeal of the names of some smaller, often picturesque and touristy, towns, including Nantucket, Massachusetts (2,693), Telluride, Colorado (2,505), and Taos, New Mexico (1,743). In keeping with this pattern, poor Flagstaff (42) is eclipsed by our red-rocked and highly Instagrammed neighbor to the south, Sedona, Arizona (2,373). To add insult to injury, the Book 1 “Sedona” beat the Flagstaff model to market by a month. From the smallest burgs to the most massive metropolises, brands like Nike have seen the potential of place names to add meaning to brands—no matter how the locals might feel about it.

Earlier this month, Nike dropped the “Flagstaff” colorway of its Book 1 sneaker, the signature model of Phoenix Suns star Devin Booker. Its dark green shade reflects Flagstaff, Arizona’s situation in the world’s largest ponderosa pine forest—it’s not all cactuses and sand in the Grand Canyon State—and the shoe plays off Booker’s status as one of the many second-home owners in the area. “When Book needs to escape the desert heat,” the Nike copy explains, “he heads to Flagstaff, where he can walk the mountain paths worry-free.” Nike’s use of local color seems to be part of a larger branding trend that emphasizes small-scale authenticity over brute-force bigness.

As a longtime Flagstaffer, I’m torn by this product. On the one hand, it brings a sense of validation: Nike has acknowledged us! We are seen! On the other, though, the use of the city’s good name to sell sneakers feels like something akin to appropriation, which is made more irksome when Nike doesn’t quite get the details right, as when it says the Book 1 “comes complete with a Humphrey’s Peak woven label, which pays homage to the highest point in Flagstaff.” (Actually, it’s the highest point in all of Arizona!)

And the heel of the shoe is adorned with the words, “No Service,” which, yes, is supposed to suggest that Flagstaff is a place to get away from it all, but also implies that it’s a sleepy backwater. Hey, my cell reception is great, thank you very much, and Flagstaff even got an In-N-Out Burger last year. It’s not exactly the Old West anymore, although, admittedly, an occasional tumbleweed does roll down the street, and a $300,000 shipment of special edition Air Jordans recently fell victim to a local train robbery.

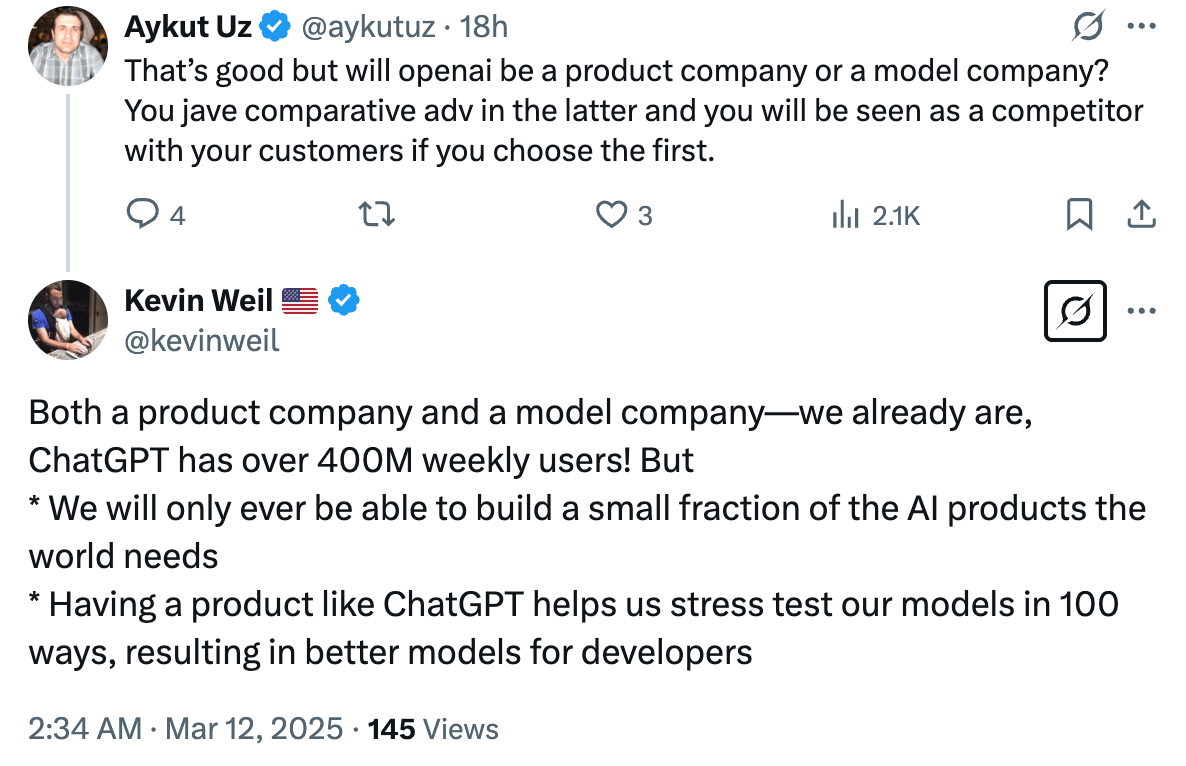

Nike is undoubtedly unconcerned with my thoughts on its use of the Flagstaff name; like the thousands of other companies assigning place names to their products, it’s just trying to take advantage of a bit of the cachet that those names can deliver free of charge. City names, unlike personal names, are generally fair game for marketers; while you would be legally prohibited from calling your new vape product the “Timothée Chalamet Tank” or the “Peso Pluma Pen,” you’re welcome to name it after Tulsa or Poughkeepsie.

Or perhaps you’d rather pick a more appealing city name with which to pair your product; something unique, as with the Hyundai Tucson, or evocative, à la Philadelphia Cream Cheese (which was created in New York!), or exotic, like the Jeep Grand Cherokee Laredo. Digging into data from the United States Patent and Trademark Office and the Census Bureau can give us a better idea of what those might be. By counting the number of trademark applications containing the names of the largest 100 U.S. cities by companies that are not located in those places, and adjusting for the population of each city, a measure of local trademark popularity can be calculated.

The three cities that come out on top of this list—Buffalo, New York; Madison, Wisconsin; and Lincoln, Nebraska—should probably be given asterisks, as most of the trademarks containing their names were probably not inspired by the cities themselves. This leaves Miami as the leader, with 357 outsider trademarks per 100,000 residents, followed by Boston (345). Next come Washington, D.C. (322) and Aurora, Colorado (311), although, like Buffalo, these two should perhaps be disqualified. Detroit (209), Chesapeake, Virginia (200), Atlanta (186), Phoenix (177), and New Orleans (164) are close behind.

That such famous places would inspire the names of trademarks is not surprising, but expanding this analysis beyond the top 100 cities reveals the appeal of the names of some smaller, often picturesque and touristy, towns, including Nantucket, Massachusetts (2,693), Telluride, Colorado (2,505), and Taos, New Mexico (1,743). In keeping with this pattern, poor Flagstaff (42) is eclipsed by our red-rocked and highly Instagrammed neighbor to the south, Sedona, Arizona (2,373). To add insult to injury, the Book 1 “Sedona” beat the Flagstaff model to market by a month.

From the smallest burgs to the most massive metropolises, brands like Nike have seen the potential of place names to add meaning to brands—no matter how the locals might feel about it.

![How to Use GA4 to Track Social Media Traffic: 6 Questions, Answers and Insights [VIDEO]](https://www.orbitmedia.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/ab-testing.png)

![How Human Behavior Impacts Your Marketing Strategy [Video]](https://contentmarketinginstitute.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/human-behavior-impacts-marketing-strategy-cover-600x330.png?#)

![How to Make a Content Calendar You’ll Actually Use [Templates Included]](https://marketinginsidergroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/content-calendar-templates-2025-300x169.jpg?#)

![Building A Digital PR Strategy: 10 Essential Steps for Beginners [With Examples]](https://buzzsumo.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Building-A-Digital-PR-Strategy-10-Essential-Steps-for-Beginners-With-Examples-bblog-masthead.jpg)