The Hidden Battle for IP Protection in Alliances

Taylor Callery Strategic alliances are indispensable for accessing specialized resources, capabilities, and know-how that companies cannot easily develop in-house. However, despite being critical for innovation, alliances can be fraught with distrust, particularly regarding concerns about losing intellectual property (IP). A telling case is the failed alliance between American Superconductor Corp. (AMSC) and wind turbine producer […]

Taylor Callery

Strategic alliances are indispensable for accessing specialized resources, capabilities, and know-how that companies cannot easily develop in-house. However, despite being critical for innovation, alliances can be fraught with distrust, particularly regarding concerns about losing intellectual property (IP).

A telling case is the failed alliance between American Superconductor Corp. (AMSC) and wind turbine producer Sinovel. AMSC provided essential software for Sinovel’s turbines, but Sinovel reverse engineered the software to introduce its new turbines without AMSC. This IP leak led to a devastating 84% drop in AMSC’s stock, forced the company to cut 700 jobs, and wiped out $1 billion in shareholder equity.1

In another recent case, sportscar maker Saleen Automotive accused its joint venture partner of filing 510 patents based on proprietary Saleen technologies and trade secrets worth $800 million, without crediting Saleen’s inventors.2

These cases illustrate how alliances can turn into IP battles, with grave consequences for companies that fall prey to predatory partners. Such battles are more common than may be apparent to external observers, since they rarely receive publicity. Our research reveals that at least 50% of alliances encounter traceable knowledge spillover, and our interviews with executives suggest that this is a key concern in most strategic alliances.3 Nevertheless, only 10% of such incidents culminate in legal IP disputes. Most conflicts over IP do not escalate to court battles and are deliberately kept out of the media because companies often depend on their partners for their ongoing operations. Moreover, demonstrating malicious intent is challenging, and prolonged legal proceedings are costly. Finally, companies are reluctant to disclose information about their knowledge-protection practices or admit to being a victim of predatory actions, given that doing so may harm the company’s reputation in the eyes of shareholders and other prospective partners.

Not all IP leakages involve illicit activity such as outright knowledge theft or breach of contract. Partners can employ subtle intrusive tactics to access and use a company’s IP in ways that may not explicitly violate the law or the alliance contract but are still harmful to the company that owns the IP. These practices exploit gray areas and scenarios that were not anticipated in the alliance contract or that take advantage of the company’s trust.

Predatory partners rely on other companies’ IP to develop their own proprietary knowledge while minimizing what would otherwise be prolonged, expensive, and risky internal R&D. Their behavior is often motivated by an interest in outmaneuvering competitors, catching up with industry leaders, or sidelining partners that have a superior bargaining position. Predatory behavior may also be driven by national policy, whereby local partners are encouraged to capture foreign technologies to either contribute to their nation’s industrialization or erode another nation’s comparative advantage.

Identifying predatory partners a priori can be challenging because they often conceal their true intentions. Moreover, companies may knowingly enter alliances with predatory partners when executives believe that the company’s IP is sufficiently secure. They simply underestimate the hazard when seeking immediate benefits partners may offer, such as market access or lower manufacturing costs.

Predatory partners can be highly adept at outmaneuvering IP protection in alliances and should not be underestimated. Our research reveals that by ineffectively defending against intrusive knowledge-acquisition tactics, companies may inadvertently strengthen predatory partners. Not only do these partners gain valuable IP, but they also learn to better defend their own IP in the course of these alliances.

For instance, during the 2000s, several electronics and chipmaking companies from the so-called Four Asian Tigers (Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan) experienced rapid growth fueled by knowledge gained from their foreign alliance partners. These companies also adopted their former partners’ IP protection practices and refined them, which helped them become experts in IP protection and world leaders in their respective industries.

To prevail in this complex IP protection battle, managers must recognize predatory partners and implement effective protective practices that their partners cannot easily circumvent. Our research and interviews with executives offer insights into six threats and six protective practices that counter the intrusive practices of predatory partners. (See “How to Defend Against Intrusive Practices in IP Management.”)

Strategies for Thwarting Predatory Attacks

Traditional nondisclosure agreements (NDAs) and alliance contracts offer some legal protection from IP theft but are insufficient for dealing with predatory partners. These legal agreements offer reactive remedies to IP leaks after the damage has already been done. Even when an NDA specifies monetary compensation for prespecified misconduct, legal remedies cannot fully undo the economic or competitive ramifications of an IP leak.

Other conventional measures for preventing predatory behavior include opting for more formal alliance governance in the form of an equity joint venture, avoiding alliances with direct competitors that could better exploit a partner company’s IP, and restricting the scope of alliances to minimize the touch points with partners through which IP may leak. However, these preventive measures are typically determined during the contract stage at the launch of an alliance and offer limited defense and flexibility once the alliance is underway.

Our research points to other protective practices companies can use besides legal and contractual measures. Leading tech companies such as Apple, Tesla, and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. (TSMC) often use the following practices in their alliances to combat the insidious tactics of predatory partners.

1. Designating Gatekeepers

Predatory partners often nurture close personal ties with key partner employees to foster interpersonal trust. Such ties may be formed during frequent informal meetings, through mutual participation in workshops and team-building activities, or via casual after-work gatherings. These relationships are purposefully cultivated rather than naturally evolving, and they can make unsuspecting employees lower their guard and willingly divulge sensitive information. To counter this, companies can restrict information channels and designate gatekeepers — employees trained to manage such information flows.

The gatekeeper role involves supervision and diplomacy. Acting as the central point of contact between the partnering companies, the gatekeeper ensures that only preapproved and necessary information is shared with the partner. Besides managing information flows by controlling other employees’ interactions with the partner, gatekeepers regularly meet the partner’s managers to set joint targets for the collaboration and exchange essential information. The gatekeepers are trained to recognize and intervene to halt the partner’s attempts to cultivate and take advantage of false bonds. For example, they can ensure that personnel with access to critical and vulnerable IP, such as trade secrets or confidential plans, are deliberately shielded from unnecessary contact with the partner, while employees with secure IP (such as patents) engage in controlled collaborative activities with the partner.4 Gatekeepers can also establish and enforce communication protocols, such as requiring formal approval for data sharing, or using secure channels for transmitting sensitive information.

Many alliances we studied involve extensive collaboration in areas such as sales and marketing, but the companies often shield their engineering units from these alliances. For example, in the Renault-Nissan joint venture, the parties closely collaborated across procurement, marketing, and other business functions while keeping their engineering units apart. Instead of providing partners with unrestricted access to their engineers, these companies used selective engineering exchange programs, where only carefully vetted employees could spend brief periods on the partner company’s premises.5 Even then, the gatekeepers monitored those engineers and the knowledge that they might access.

A gatekeeper should be an employee with a vested interest in the company’s success, such as a veteran with an equity stake or a strong socioemotional attachment to the organization — someone who is loyal and protective of its interests and less likely to disclose sensitive information. For example, a manager we interviewed explained that their company assigns senior executives with over 20 years’ tenure to the role so it can be confident in its gatekeepers’ trustworthiness and commitment to protect its interests.

2. Implementing Digital Safeguards

Predatory partners may attempt to bypass a company’s IP defenses using hacking or social engineering, or by exploiting vulnerabilities in the company’s IT infrastructure. As more alliance activities take place virtually and remotely, the importance of digital safeguards increases. Alliances often rely on systems such as third-party collaborative platforms that may have unknown vulnerabilities, so a company cannot fully rely on its own internal cybersecurity measures.

Typical digital safeguards against such hazards include encrypting sensitive documents, using tracking systems to monitor who accesses documents, and ensuring confidentiality through secured communication channels and firewalls. One company we studied used secured USBs, encrypted files, and a system for tracking digital documents and their physical copies. Anyone who printed a document had their name appear on the printout to hold them accountable for its secrecy. Such measures are critical in alliances where various parties access shared sources, which increases the risk of unauthorized distribution of sensitive information.

Companies should invest in advanced security measures such as multifactor authentication, AI-powered anomaly detection systems, and routine security audits. Anomaly detection, for instance, can identify unusual access patterns and intercept breaches before they cause damage. Cybersecurity training can reduce the likelihood of employees falling victim to social engineering attempts, which are a common tactic of predatory companies for gaining access to a partner’s off-limits systems.

Companies such as Samsung, Nvidia, and TSMC run drills in which some employees act as hackers who attempt to breach the company’s digital defenses while other employees attempt to monitor, detect, and thwart the attacks. Such drills enable these companies to identify and remediate vulnerabilities before they can be exploited by external predators.

3. Creating Physical Barriers

When a partner’s employees work at or visit a company’s sites, they may engage in covert observation. This can range from inadvertently overhearing sensitive information in a corridor conversation to intentionally using recording devices to capture confidential information in the R&D lab.

Enforcing physical security protocols protects critical IP from inadvertent or deliberate leaks to unauthorized individuals. This includes holding partner meetings in a secluded area of a building; using secure, separate offices for sensitive work; monitoring access to these sites; and inspecting employees and their bags when they enter or leave the company’s premises.

For example, Tesla and Panasonic operate Gigafactory Nevada as part of an alliance in which Panasonic supplies batteries for Tesla’s electric vehicles. The factory features strictly separate zones accessible only to authorized partner employees. All semifinished products are moved by robots between the walled-off areas to prevent human interaction across zones.6

4. Engaging in Process Fragmentation

Predatory partners may re-create a product or process by gathering information across multiple touch points and functions at a partner company. They can then piece together partially shared or incomplete information with public records, such as patent filings or technical reports.

To mitigate this risk, companies can divide a manufacturing process into physically or geographically separate production stages, or work with different partners on different components or production stages, in order to restrict knowledge flows. This reduces the risk of any one partner gaining a comprehensive understanding of the product’s design.

That is why Apple maintains a strict compartmentalization practice: The iPhone’s processor is produced by TSMC in Taiwan, its display is manufactured by Samsung in South Korea, and its assembly is handled by Foxconn in China. Moreover, when ending a partnership, Apple retains ownership of critical IP and shuts down facilities to prevent former partners from passing on sensitive information to third parties. For instance, when a chemicals company entered a joint venture with Apple to produce the glass for the iPhone’s screen, Apple revealed the bare minimum information necessary for manufacturing the glass in a joint venture facility, according to an executive we interviewed from that company. Upon termination of the joint venture, Apple dismantled the entire production facility so that its partner could not deploy the glassmaking knowledge in its other projects.

5. Obfuscating

Alliance partners often gain access to prototypes or manufacturing machinery that are inaccessible to outsiders. Predatory partners can use this access to reverse engineer a company’s products.

To combat this, companies can use product and engineering designs that make it difficult or costly to reverse engineer the product. Adding nonessential decoy elements, deliberate inaccuracies, or complexities to components or final products can obscure critical aspects of the product design, mislead engineers attempting replication, or alert the company about reverse-engineering attempts.7 Some manufacturers install temporary components or circuitry elements that hinder the component’s intended functionality and are removed only at the final production stage or upon delivery of the product to customers, without the partner’s involvement. Some companies, such as ASML, which sells advanced chip-manufacturing tools, install kill switches that allow them to remotely disable their equipment if tampering is detected.

A company may deliberately leak outdated or less valuable knowledge in order to outsmart predatory partners who may gain access to off-limits knowledge by synthesizing information from multiple available sources. By directing the partner’s interest toward less critical innovations, the company can more effectively protect its valuable technologies. One manager told us that their employer, a multinational technology company, shares technologies that may be outdated from its perspective but are new to its partners. This allows those partners to benefit from knowledge transfer while the company remains two or three steps ahead of them, which limits the potential damage from IP leakage.8

A variant of this practice, known as the “canary trap,” uses deliberate leaks to identify protection loopholes and unreliable partners. For example, after a series of leaks at Apple, the company provided several employees with slightly different versions of seemingly sensitive information to see which version would be leaked and thus reveal the leak’s source.9 Similar practices can be applied to prevent or detect IP leakages in alliances. By sharing altered versions of noncritical information with different partners or employees, the company can trace how the information is handled and determine the party responsible for its misuse.

6. Instituting Employee Controls

Predatory partners may attempt to recruit and hire key employees from a partner by offering better compensation. If successful, they may then incentivize or socially pressure those hires to disclose their insider knowledge of their former employer’s IP.

To mitigate the risk of talent poaching and unintended IP transfer, companies can institute strict HR policies and employee controls. These include restrictions such as nondisclosure and noncompete agreements, social interaction controls, and limited access to sensitive systems. Monitoring compliance through regular inspections using electronic surveillance can deter unauthorized knowledge sharing. Additionally, aligning long-term employee incentives with the company’s goals can discourage the sharing of critical know-how even after an employee has left. For instance, when employees know that their post-employment benefits — such as deferred compensation, royalties, or stock options — are tied to maintaining confidentiality, they are less likely to disclose sensitive information.

Companies also use process fragmentation across their workforces, isolating teams that work on different aspects of a project to reduce the risk of any single employee having too much critical knowledge that they could leak. An executive at a chemicals company we studied explained that, as a part of the manufacturing process, one team knew how much pressure needed to be applied to a particular component, another knew the temperature that needed to be maintained, and a third knew the ratios of raw material mixtures. Only a few employees were trusted with all of that information so they could oversee the whole process.

TSMC has rigorous employee controls to safeguard its IP in its manufacturing plants. The company has a dedicated information security team that screens and trains personnel on handling sensitive information and avoiding social engineering and phishing attempts. It also enforces strict penalties on employees who violate NDAs.

When Protective Practices Benefit the Predator

Our research found that some predatory partners became better defenders by learning protective practices from their alliance counterparts. In such alliances, the companies that suffered the loss of leaked IP to prospective competitors also ended up offering long-term benefits to their partners in the form of advanced protective skills. Hence, by playing defense against predators and losing, the companies taught their partners how to protect their own knowledge. This shows that today’s predator is less likely to become tomorrow’s prey.

While the companies in an alliance may predominantly play the role of either defender or predator, they often assume dual roles — simultaneously protecting their IP while seeking to learn from a counterpart. The battle for IP is a continuous arms race in which the roles of predator and defender may alternate as an industry evolves.

When reflecting on the challenges faced by companies that were formerly industry leaders, a semiconductor expert who worked as a consultant in Taiwan noted the following:

[TSMC] have very aggressive operating practices to prevent their proprietary operating knowledge from being leaked. … TSMC probably learned some of these practices from some of the Western early chip manufacturers. Intel would be one of them. … [TSMC] are leaders now, so today it would be very, very difficult for any other company to catch up with them, although many are desperately trying —[including] Western companies. Even a company like Intel finds it hard to compete with them.

Accordingly, such dual learning of their counterparts’ IP and protective practices during past alliances makes it increasingly difficult for erstwhile leaders to catch back up with predatory partners and reclaim their lost leadership positions.

Conventional approaches to restricting IP loss in alliances, such as reducing the scope of the alliance and avoiding forming alliances with direct competitors, often fail to prevent this dual learning. Paradoxically, when the defender restricts the scope of its alliance activities to limit touch points with the partner and reduce the diversity of information it exchanges with the partner, that partner can get better at learning the defender’s protective practices. The more effort the predator needs to invest to outsmart the defender’s protection, the better the predator learns to implement similar protective practices itself. However, this occurs only when the predator successfully outsmarts the defender’s protective practices. Otherwise, its understanding of the protective practices is insufficient for successful learning and implementation.

Moreover, our research reveals that predatory partners that have been operating for years in a company’s knowledge domain and can easily decipher its IP are not the ones posing the greatest threat of learning protective practices. It is those partners that specialize in less familiar domains that need to invest more effort to understand the company’s IP, so they learn more about its protective practices while attempting to overcome the company’s defenses.

Dealing With the Predator

Based on our findings, we have a warning for managers who seek to navigate the paradox of dual learning.

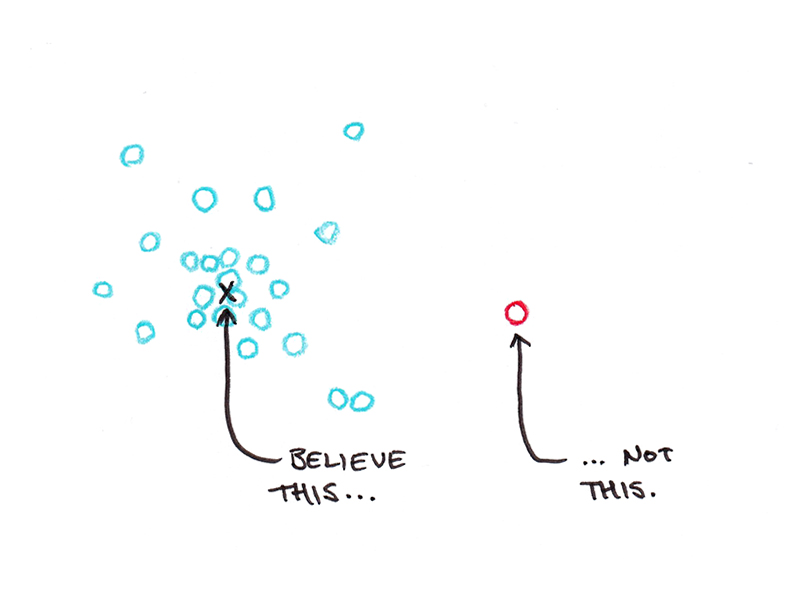

Managers should be alert when entering an alliance and proceed under the assumption that the partner may be a predator seeking to capture their company’s IP. Although alliances are cooperative by nature, they often conceal an undercurrent of competition for ideas and knowledge. Being aware of partners’ predatory intentions and intrusive practices is the first line of defense. Unfortunately, by making only weak attempts to guard against a predator, a company may also end up feeding that predator, thus making it stronger and better prepared to defend its own IP in future alliances.

Accordingly, we offer these recommendations:

1. Adopt a dynamic, multilayered defense. Our research found that predators only learn the protective practices that they have successfully outmaneuvered — but when it comes to comprehensive, state-of-the-art defenses, they are neither able to access the IP nor learn the practices for safeguarding it. Managers should therefore dynamically combine various protective practices to create a comprehensive bulwark that fends off predators rather than feeding them with valuable know-how. Relying on too few protective practices is risky: It may allow the predator to circumvent those practices and learn how to implement them. Instead, managers should layer multiple practices, such as combining obfuscation techniques with digital safeguards or engaging gatekeepers with employee controls.

2. Transform reactive defense into continuously evolving protective practices. Managers should consider their companies’ alliances as an opportunity to innovate and improve their IP protection. To achieve this, they should establish a specialized alliance function — a team of experts that can continually improve the company’s alliance management skills and IP protection practices. These experts should bring together executives with extensive alliance management experience (such as those who have served or might be picked to serve in the gatekeeper role), legal advisers, cybersecurity experts, and HR specialists who can develop training programs on information security and align employee incentives with the company’s objectives. This team can monitor and implement best practices for IP protection, draw insights from previous partners’ protection practices, and defend the company’s own protective practices from leaking to partners. By staying one step ahead of their partners, companies can turn the predator’s threat into a catalyst for continuous improvement of their own defensive practices.

3. Selectively share noncritical IP. When dealing with highly skilled predators, even the most sophisticated protection practices may suffer from limitations. In such cases, managers should strategically share noncritical IP rather than overly restricting the information flow, which can undermine joint value creation. By carefully controlling what information is shared with the predator, the company can retain a competitive edge through its superior familiarity with its own IP and greater capacity for innovating on it. Sharing noncritical knowledge can be a form of calculated risk — less harmful than unintentionally teaching the predator how to outsmart defenses and strengthen its competitive position in the future.

The battle for IP protection in alliances is an arms race between predators and defenders. Retaining the upper hand requires vigilance and continuous improvement of IP protection.

![How to Use GA4 to Track Social Media Traffic: 6 Questions, Answers and Insights [VIDEO]](https://www.orbitmedia.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/ab-testing.png)

![How Human Behavior Impacts Your Marketing Strategy [Video]](https://contentmarketinginstitute.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/human-behavior-impacts-marketing-strategy-cover-600x330.png?#)

![How to Make a Content Calendar You’ll Actually Use [Templates Included]](https://marketinginsidergroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/content-calendar-templates-2025-300x169.jpg?#)

![Building A Digital PR Strategy: 10 Essential Steps for Beginners [With Examples]](https://buzzsumo.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Building-A-Digital-PR-Strategy-10-Essential-Steps-for-Beginners-With-Examples-bblog-masthead.jpg)