$3,500 and bills paid: How these local organizations are helping L.A. fire victims recover

When the Eaton Fire burned through Altadena in January, Patricia Lopez-Gutierrez and her children had to flee from the house they’d been renting for a decade. Lopez-Gutierrez also lost work: She’s a housecleaner, and her clients lost their own homes in the fire. “I’ve been here for 18 years, and I really don’t want to leave this area,” she said through a translator. “My children and their schools are here. I’m trying to get more work so I don’t have to leave.” As she struggles to pay her bills—including at her rental house, which ended up surviving the fire but was so heavily damaged by smoke that she’s desperate to find a new place to live—she turned to St. Vincent de Paul, one of several local organizations providing direct assistance to fire victims. The nonprofit paid a utility bill for her in January, and then a car payment and dental bill this month. It was enough, for now, to make it possible for her to keep paying rent. The fire destroyed thousands of homes in Altadena, one of the more affordable corners of L.A. County. St. Vincent de Paul, working with a team of 18 volunteers, has helped around 150 families so far, prioritizing families with children and renters who lost their homes. In many cases—particularly for Hispanic residents who worked as housecleaners or gardeners—residents also lost their jobs. Others have minimum-wage jobs that make it difficult to afford to rent a new house or apartment. While St. Vincent de Paul covers bills directly (paying rent to a landlord, for example, or paying a doctor’s office), many other organizations are simply giving residents cash directly. Pasadena Community Foundation, a local foundation, has given grants through a wildfire fund to help support dozens of organizations doing that work. The Dena Care Collective, a new organization launched by End Poverty in California (EPIC) and FORWARD, has raised more than $1 million to help support families and businesses in the immediate aftermath of the fire with direct cash payments. “There is significant empirical data that highlights the efficacy of direct cash payments to families,” says Aja Brown, the former mayor of the city of Compton, who grew up in Altadena and is helping lead the Dena Care Collective along with former Stockton mayor Michael Tubbs. “There’s also a wealth of data that substantiates [the fact that] bureaucracy and governmental systems are slow to react. And quite frankly, they aren’t designed for emergency relief. Getting cash in the hands of families is the most impactful and the most efficient way to help families; they innately understand what’s best for [their] aid and the relief based on their current conditions.” Cash is a critical tool for people living in poverty in ordinary times; in Stockton, a study of a program that gave a series of no-strings-attached checks to low-income residents found that people who got the payments were more likely to go from unemployment to full-time employment and take other steps for their future, like moving to a better apartment or fixing their car. In a disaster, quick access to cash is even more important to help people stay afloat. “In a disaster like this, of course people need cash, because water bottles aren’t wealth,” says Tubbs. “Clothing isn’t cash. People need money to be able to rebuild, to be able to move, to be able to persist.” GiveDirectly, an organization founded on the premise that sending money to the world’s poorest households can help them begin to overcome poverty, has raised more than $2 million for low-income households impacted by the L.A.-area fires. While getting some money from FEMA can sometimes take a month or two, the nonprofit is able to act more quickly. (FEMA gave eligible residents $770 to help cover immediate needs after the disaster, but getting any additional support took longer—and $770 doesn’t go far in a city like L.A. Immigrants who don’t have legal status also can’t get help from FEMA.) Two weeks after the fires, the organization sent notifications to residents via a food stamp app inviting them to enroll for the cash payments, a process that takes roughly a minute. On average, the payments arrived three days later. The organization is giving transfers of $3,500, enough to cover two weeks at a lower-end Airbnb in the L.A. area, a month of food for a family of four, and a month of healthcare and transportation. Of course, the support is only a small and temporary part of the solution. As rents have steeply risen in and around L.A.—something that was happening earlier and then exacerbated by the disaster—people who were displaced are struggling to find places to live. Some renters are now doubled or tripled up with friends in tiny apartments. Homeowners who bought homes decades ago in Altadena—or inherited mortgage-free homes from parents or grandparents who paid little for them—are often now finding that their insurance won’t cover the cost of rebuilding. Others lost coverage as insur

When the Eaton Fire burned through Altadena in January, Patricia Lopez-Gutierrez and her children had to flee from the house they’d been renting for a decade. Lopez-Gutierrez also lost work: She’s a housecleaner, and her clients lost their own homes in the fire.

“I’ve been here for 18 years, and I really don’t want to leave this area,” she said through a translator. “My children and their schools are here. I’m trying to get more work so I don’t have to leave.”

As she struggles to pay her bills—including at her rental house, which ended up surviving the fire but was so heavily damaged by smoke that she’s desperate to find a new place to live—she turned to St. Vincent de Paul, one of several local organizations providing direct assistance to fire victims. The nonprofit paid a utility bill for her in January, and then a car payment and dental bill this month. It was enough, for now, to make it possible for her to keep paying rent.

The fire destroyed thousands of homes in Altadena, one of the more affordable corners of L.A. County. St. Vincent de Paul, working with a team of 18 volunteers, has helped around 150 families so far, prioritizing families with children and renters who lost their homes. In many cases—particularly for Hispanic residents who worked as housecleaners or gardeners—residents also lost their jobs. Others have minimum-wage jobs that make it difficult to afford to rent a new house or apartment.

While St. Vincent de Paul covers bills directly (paying rent to a landlord, for example, or paying a doctor’s office), many other organizations are simply giving residents cash directly. Pasadena Community Foundation, a local foundation, has given grants through a wildfire fund to help support dozens of organizations doing that work. The Dena Care Collective, a new organization launched by End Poverty in California (EPIC) and FORWARD, has raised more than $1 million to help support families and businesses in the immediate aftermath of the fire with direct cash payments.

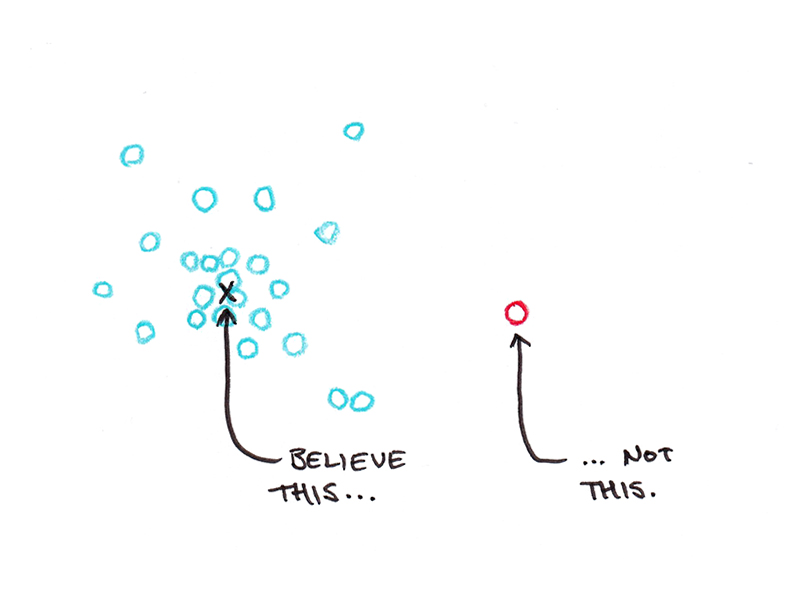

“There is significant empirical data that highlights the efficacy of direct cash payments to families,” says Aja Brown, the former mayor of the city of Compton, who grew up in Altadena and is helping lead the Dena Care Collective along with former Stockton mayor Michael Tubbs. “There’s also a wealth of data that substantiates [the fact that] bureaucracy and governmental systems are slow to react. And quite frankly, they aren’t designed for emergency relief. Getting cash in the hands of families is the most impactful and the most efficient way to help families; they innately understand what’s best for [their] aid and the relief based on their current conditions.”

Cash is a critical tool for people living in poverty in ordinary times; in Stockton, a study of a program that gave a series of no-strings-attached checks to low-income residents found that people who got the payments were more likely to go from unemployment to full-time employment and take other steps for their future, like moving to a better apartment or fixing their car. In a disaster, quick access to cash is even more important to help people stay afloat.

“In a disaster like this, of course people need cash, because water bottles aren’t wealth,” says Tubbs. “Clothing isn’t cash. People need money to be able to rebuild, to be able to move, to be able to persist.”

GiveDirectly, an organization founded on the premise that sending money to the world’s poorest households can help them begin to overcome poverty, has raised more than $2 million for low-income households impacted by the L.A.-area fires. While getting some money from FEMA can sometimes take a month or two, the nonprofit is able to act more quickly. (FEMA gave eligible residents $770 to help cover immediate needs after the disaster, but getting any additional support took longer—and $770 doesn’t go far in a city like L.A. Immigrants who don’t have legal status also can’t get help from FEMA.)

Two weeks after the fires, the organization sent notifications to residents via a food stamp app inviting them to enroll for the cash payments, a process that takes roughly a minute. On average, the payments arrived three days later. The organization is giving transfers of $3,500, enough to cover two weeks at a lower-end Airbnb in the L.A. area, a month of food for a family of four, and a month of healthcare and transportation.

Of course, the support is only a small and temporary part of the solution. As rents have steeply risen in and around L.A.—something that was happening earlier and then exacerbated by the disaster—people who were displaced are struggling to find places to live. Some renters are now doubled or tripled up with friends in tiny apartments. Homeowners who bought homes decades ago in Altadena—or inherited mortgage-free homes from parents or grandparents who paid little for them—are often now finding that their insurance won’t cover the cost of rebuilding. Others lost coverage as insurers have dropped policies in areas at risk of fires.

Even those who still have housing, like Lopez-Gutierrez, are dealing with new challenges. In her case, her landlord wants to raise her rent, even though he hasn’t repaired damage from the fire (and despite the fact that price gouging is illegal). She’s trying to find a new rental, but her low credit score is making that difficult.

Even if bills are covered for a month or two, many families still don’t know what will come next—especially since the rebuilding process will be slow. Before the fires, when St. Vincent de Paul helped pay unexpected bills for residents, the situation was different. “It’s the housecleaner whose son or daughter had to go to the emergency room and there was a $1,000 bill and they can’t afford rent,” says Dave de Csepel, an investor who helps lead the volunteer work at St. Vincent de Paul. “So we come in, pay that rent, and life goes on—we bridge them to get to the next month.” Now, he says, “This is a tidal wave that has hit this community. This is the beginning. It’s hard to see how all these families come out of this. We love the diversity of our community and we want to have folks stay in the area. But it’s hard to keep everyone together, and I’m afraid that there are a lot of hard times ahead for these families.”

![How to Use GA4 to Track Social Media Traffic: 6 Questions, Answers and Insights [VIDEO]](https://www.orbitmedia.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/ab-testing.png)

![How Human Behavior Impacts Your Marketing Strategy [Video]](https://contentmarketinginstitute.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/human-behavior-impacts-marketing-strategy-cover-600x330.png?#)

![How to Make a Content Calendar You’ll Actually Use [Templates Included]](https://marketinginsidergroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/content-calendar-templates-2025-300x169.jpg?#)

![Building A Digital PR Strategy: 10 Essential Steps for Beginners [With Examples]](https://buzzsumo.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Building-A-Digital-PR-Strategy-10-Essential-Steps-for-Beginners-With-Examples-bblog-masthead.jpg)