America, the brand, is becoming toxic

The only thing more American than baseball and apple pie might be the Statue of Liberty. It’s a universally identifiable bit of iconography, appearing on stamps, currency, and Planet of the Apes movies since time immemorial. The blue-green, toga-clad Lady Liberty is a sturdy symbol of democracy, independence, and the land of opportunity. And in 2025, an official from the country who gifted America the statue has asked for it back—the latest sign that America, the brand, is becoming toxic. A French Member of European Parliament may have been joking at a recent party meeting when he said, “We’re going to say to the Americans who have chosen to side with the tyrants, to the Americans who fired researchers for demanding scientific freedom: ‘Give us back the Statue of Liberty.’” He might have also been dead serious. Either way, he’s certainly not alone in reconsidering his views about what America has to offer the world these days, and vice versa. Global backlash hits U.S. brands Boycotts of U.S.-made products have broken out in Canada—where some cafes have taken to calling Americanos “Canadianos“—along with France and Sweden, where a Facebook group geared around boycotting the U.S. has swelled to nearly 80,000 members. In addition to a grassroots boycott push in Denmark, where Trump annexation-target Greenland technically resides, the country’s largest grocery store operator has added a black star on price tags for European products, to make it easier for customers to avoid purchasing American goods. And even without explicitly boycotting American products, fewer people around the world stand poised to buy them in the near-term. Between supply chain disruptions and an unmistakable aura of economic uncertainty, Tesla is unlikely to be the only American company that sees its global sales plunge this year. (Canada has already removed Jack Daniels products from store shelves, as a retaliatory measure for Trump’s tariffs, while Beyond Meat recently shared fears of its revenue suffering from “anti-American sentiment.”) Since Donald Trump resumed office on January 20, he’s alienated America from much of the rest of the world. His run of omnidirectional trade wars has antagonized U.S. allies with hefty tariffs, and confused many with their incoherence and inconsistency. He has acted with imperialist hostility, threatening to annex the U.S.’s Northern neighbor and largest trading partner, along with the Panama Canal and Greenland. He has paradoxically portrayed Ukraine as the aggressor in Russia’s invasion of the country, and withheld military support for the region on the condition of receiving rare minerals for America’s efforts. His administration has cut off 90% of funding from USAID, which a New York Times report claims may lead to 1.65 million deaths from AIDS this year, and his domestic crackdown on dissent has made it unclear whether America is still meant to be a beacon of democracy. When hockey fans at Montreal’s Bell Centre last month booed the Star Spangled Banner in multiple games against the American team, it was clearly about more than just hockey. And it might have also been just the beginning of a worldwide backlash. Opposing the U.S. wins elections Leaders in several countries have lately learned that opposing the U.S. is now likely to bolster domestic support. The next election in Canada once seemed like a surefire victory for the Conservative Party, with late-2024 polling showing the Liberal Party down by 26 points. But as the Liberals’ newly elected PM Mark Carney has taken a strong stance against Trump’s tariffs and annexation threats, the two parties are now locked in a dead heat. (In his recent victory speech, Carney referred to the U.S. as “a country we can no longer trust.”) Similarly, Jens-Frederik Nielsen’s Demokraatit party won a March 11 election in Greenland, partly due to the popularity of Nielsen’s resistance to Trump’s ongoing threats to absorb the country. And in France, Senator Claude Malhuret’s recent speech savagely dunking on the U.S. turned him into a viral sensation. (“Washington has become the court of Nero,” he said, kicking off the fiery diatribe. “An incendiary emperor, submissive courtiers, and a buffoon on ketamine tasked with purging the civil service.”) As those leaders have had difficulty working with the U.S., some of them now seem to be searching for a workaround. UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer convened a meeting with the heads of 18 countries earlier this month, with the goal of building a “coalition of the willing” in Ukraine’s defense. The U.S. was apparently not invited. Nor was it invited to a top security summit in France last Tuesday with military leaders from more than 30 NATO member nations. And just this week, Canada PM Carney put forth the idea of his country trading more with the UK, France, and Europe if America continues to “look inward.” America’s fading appeal Canadian tourism to the U.S. is down, with reports indi

The only thing more American than baseball and apple pie might be the Statue of Liberty. It’s a universally identifiable bit of iconography, appearing on stamps, currency, and Planet of the Apes movies since time immemorial. The blue-green, toga-clad Lady Liberty is a sturdy symbol of democracy, independence, and the land of opportunity. And in 2025, an official from the country who gifted America the statue has asked for it back—the latest sign that America, the brand, is becoming toxic.

A French Member of European Parliament may have been joking at a recent party meeting when he said, “We’re going to say to the Americans who have chosen to side with the tyrants, to the Americans who fired researchers for demanding scientific freedom: ‘Give us back the Statue of Liberty.’” He might have also been dead serious. Either way, he’s certainly not alone in reconsidering his views about what America has to offer the world these days, and vice versa.

Global backlash hits U.S. brands

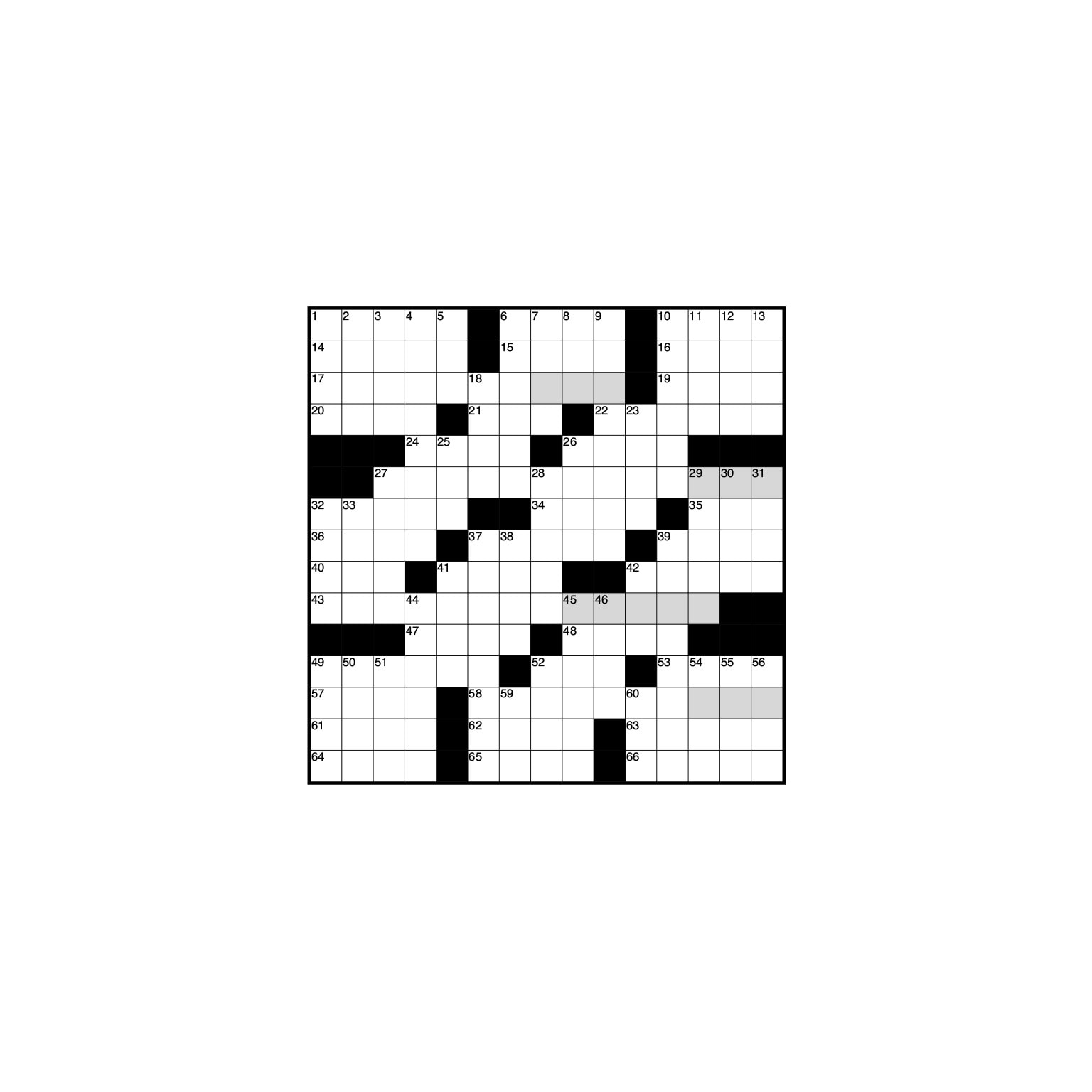

Boycotts of U.S.-made products have broken out in Canada—where some cafes have taken to calling Americanos “Canadianos“—along with France and Sweden, where a Facebook group geared around boycotting the U.S. has swelled to nearly 80,000 members. In addition to a grassroots boycott push in Denmark, where Trump annexation-target Greenland technically resides, the country’s largest grocery store operator has added a black star on price tags for European products, to make it easier for customers to avoid purchasing American goods.

And even without explicitly boycotting American products, fewer people around the world stand poised to buy them in the near-term. Between supply chain disruptions and an unmistakable aura of economic uncertainty, Tesla is unlikely to be the only American company that sees its global sales plunge this year. (Canada has already removed Jack Daniels products from store shelves, as a retaliatory measure for Trump’s tariffs, while Beyond Meat recently shared fears of its revenue suffering from “anti-American sentiment.”)

Since Donald Trump resumed office on January 20, he’s alienated America from much of the rest of the world. His run of omnidirectional trade wars has antagonized U.S. allies with hefty tariffs, and confused many with their incoherence and inconsistency. He has acted with imperialist hostility, threatening to annex the U.S.’s Northern neighbor and largest trading partner, along with the Panama Canal and Greenland. He has paradoxically portrayed Ukraine as the aggressor in Russia’s invasion of the country, and withheld military support for the region on the condition of receiving rare minerals for America’s efforts. His administration has cut off 90% of funding from USAID, which a New York Times report claims may lead to 1.65 million deaths from AIDS this year, and his domestic crackdown on dissent has made it unclear whether America is still meant to be a beacon of democracy.

When hockey fans at Montreal’s Bell Centre last month booed the Star Spangled Banner in multiple games against the American team, it was clearly about more than just hockey. And it might have also been just the beginning of a worldwide backlash.

Opposing the U.S. wins elections

Leaders in several countries have lately learned that opposing the U.S. is now likely to bolster domestic support. The next election in Canada once seemed like a surefire victory for the Conservative Party, with late-2024 polling showing the Liberal Party down by 26 points. But as the Liberals’ newly elected PM Mark Carney has taken a strong stance against Trump’s tariffs and annexation threats, the two parties are now locked in a dead heat. (In his recent victory speech, Carney referred to the U.S. as “a country we can no longer trust.”)

Similarly, Jens-Frederik Nielsen’s Demokraatit party won a March 11 election in Greenland, partly due to the popularity of Nielsen’s resistance to Trump’s ongoing threats to absorb the country. And in France, Senator Claude Malhuret’s recent speech savagely dunking on the U.S. turned him into a viral sensation. (“Washington has become the court of Nero,” he said, kicking off the fiery diatribe. “An incendiary emperor, submissive courtiers, and a buffoon on ketamine tasked with purging the civil service.”)

As those leaders have had difficulty working with the U.S., some of them now seem to be searching for a workaround. UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer convened a meeting with the heads of 18 countries earlier this month, with the goal of building a “coalition of the willing” in Ukraine’s defense. The U.S. was apparently not invited. Nor was it invited to a top security summit in France last Tuesday with military leaders from more than 30 NATO member nations. And just this week, Canada PM Carney put forth the idea of his country trading more with the UK, France, and Europe if America continues to “look inward.”

America’s fading appeal

Canadian tourism to the U.S. is down, with reports indicating a 20% year-over-year decline in new bookings to U.S. destinations since February 1. Travel-hesitance is spreading beyond Canada, too. According to the Washington Post, “International travel to the United States is expected to slide by 5% this year, contributing to a $64 billion shortfall for the travel industry.” Considering the horror stories coming out now about international visitors being detained for specious reasons, and subjected to awful conditions, the U.S. is bound to strike vanishingly fewer global citizens as a beckoning travel destination—even just for conferences.

All that hostility toward the U.S. has started boiling over into the streets as well. Anti-American protests have lately broken out in Panama, in response to Trump’s threats to reclaim its namesake canal, while at least 120 Stand Up for Science events have taken place outside of the U.S., drawing attention to recent DOGE cuts in research funding. Other international critics have instead focused their distaste with the U.S. entirely around DOGE-master Elon Musk, vandalizing signage around the UK and destroying 12 cars in a Tesla showroom in France.

Last August, about half of Western Europeans polled by YouGov had a favorable view of the U.S. Since Trump resumed office, only 37% of British, 34% of French, 32% of Germans,and just 20% of Danes now hold a positive opinion of the United States.

It’s not the first time America’s brand has been in tatters, of course. It’s not even the first time recently.

A cycle of rise and fall

The U.S.’s global reputation has been on a roller coaster throughout the entire 21st century. After 9/11, America held much of the world’s sympathies–and then promptly squandered them with the Iraq War, which proved so unpopular, it inspired mass protests in over 600 global cities. During those years, crafty entrepreneurs even started selling Canadian kits to Americans, so they might pass as mere North Americans while traveling overseas, and avoid getting yelled at.

Years later, the stars and stripes made a comeback. The Obama years seemed to restore global faith in U.S. leadership, especially after America joined the Paris Climate Accords in 2015. Then under Trump, confidence in U.S. leadership fell to a historic low of 30%. Maybe this is just how it will always go—the U.S. brand losing some of its luster and then re-polishing it to a shiny gleam again every four to eight years. (In 2023, 59% of respondents around the world gave the U.S. a favorable rating in a Pew Research survey.)

When the U.S. brand is strong, the words “Made in America” ring out around the world as shorthand for quality, durability, and freedom—even when it’s just a cheeseburger or a pair of jeans. As long as this administration drags that brand through the mud, though, “Made in America” will likely translate in any language to caveat emptor: buyer beware.

![How 6 Leading Brands Use Content To Win Audiences [E-Book]](https://contentmarketinginstitute.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/content-marketing-examples-600x330.png?#)

![Building A Digital PR Strategy: 10 Essential Steps for Beginners [With Examples]](https://buzzsumo.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Building-A-Digital-PR-Strategy-10-Essential-Steps-for-Beginners-With-Examples-bblog-masthead.jpg)

![How Human Behavior Impacts Your Marketing Strategy [Video]](https://contentmarketinginstitute.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/human-behavior-impacts-marketing-strategy-cover-600x330.png?#)

![How to Use GA4 to Track Social Media Traffic: 6 Questions, Answers and Insights [VIDEO]](https://www.orbitmedia.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/ab-testing.png)