Austin is leading the affordable housing boom. It’s still not enough

Austin has been on a building boom since it started becoming a tech hub. The Texas city has seen its skyline shift and its fortunes grow. Major tech firms like Apple and Amazon have established key offices, and in the 2010s alone, the city grew 21%, adding 171,000 residents. It now has more than 974,000, the 10th largest in the country. Builders have raced to erect housing for these new arrivals; Austin has seen a boom in market rate apartments in recent years—so much that it led rents to decrease after years of big jumps. And in recent years, according to a new report, part of that building boom has included affordable housing, including permanent housing for the formerly unhoused, low-cost studio units, and even housing for teachers. Austin’s affordable housing construction pipeline outpaces all other U.S. cities, according to research from Yardi Matrix, a real estate data source. In 2024, the city delivered 4,605 affordable units—defined as properties that agree to limit rents as a condition of a tax credit or subsidy. That’s double the rate in 2023. The research shows Austin will also deliver the most affordable units this year, 3,452—more than LA’s 2,752, despite the California city having more than four times as many people. And Austin will continue to lead, with the forecast of units in the pipeline through 2027 showing Austin with 9,528, compared to Seattle’s 6,289. [Chart: Yardi Matrix] “We want to ensure that the population that made Austin what Austin is can stay in Austin,” said James May, Housing and Community Development Officer for the City of Austin Housing Department. It’s also worth mentioning that Austin’s changing demographics are playing a large role in the housing market. As the city continues to morph from a capital and college town to a tech and healthcare nexus, wealth and median income have risen. A recent city memo noted that the city’s housing market had dramatically changed since it laid out its housing plan in the mid 2010s—median home sale price has risen by 58%, and rents went from an average of $1,350 in 2017 to a peak of $1,709 in 2022—so Austin needs to recalibrate its strategy and focus more on deeply affordable units. “Austin used to be a city of musicians and artists, and now income and rent are far higher than what it was 10 years ago,” said Heather Way, a professor at the University of Texas-Austin who specializes in housing law. [Chart: Yardi Matrix] May credited the growth in affordable housing in Austin to three factors. First, was community: Multiple providers including the city, county, housing authority, and private builders have been looking to invest in new housing, with private developers investing in significant new construction using the city’s density-bonus program. The second was money. A series of local bonds for affordable housing raised significant funds for new construction, including a 2022 bond for $350 million, which helped fund new affordable units. In addition, the construction of new transit lines included $300 million in anti-displacement funds that also helped pay for new buildings. May said the city recently purchased a 100-acre property formerly owned by the Top Deal electronic company that it plans to use for mixed-income development, which will include affordable housing. And finally, the third pillar was regulatory reform. The city council has passed many initiatives in recent years to increase density and make it easier to build: transit-oriented development rules allowed for higher buildings near bus and train lines, Affordability Unlocked allowed housing development on land zoned for commercial projects, and the HOME Initiative shrunk the required lot size for homes and made it legal to build multiple units on lots zoned for single-family homes. But even with that surge, it’s still not enough. Despite Austin’s recent lead, the construction rate still lags well behind what’s actually needed to provide sufficient access to affordable housing: tens of thousands of new units would be needed to adequately meet the demand. A record-breaking number of evictions in the surrounding county last year attest to the pressure renters feel making ends meet. And while new supply is definitely a step in the right direction, what isn’t being built is deeply affordable housing. Defined as housing that can support those making around 30% of the median income; in 2023, just 63 such units were built, even though this group makes up 17% of the city’s population. Creating enough affordable units, and building more for those with extremely low incomes, will be even more challenging due to the changing landscape for construction. Stubbornly high interest rates will make getting financing more difficult. Tariffs will make materials more expensive. And the Trump administration’s actions against HUD, including threats to withhold funding from sanctuary cities like Austin, might end vital federal support. “It’s go

Austin has been on a building boom since it started becoming a tech hub. The Texas city has seen its skyline shift and its fortunes grow. Major tech firms like Apple and Amazon have established key offices, and in the 2010s alone, the city grew 21%, adding 171,000 residents. It now has more than 974,000, the 10th largest in the country.

Builders have raced to erect housing for these new arrivals; Austin has seen a boom in market rate apartments in recent years—so much that it led rents to decrease after years of big jumps.

And in recent years, according to a new report, part of that building boom has included affordable housing, including permanent housing for the formerly unhoused, low-cost studio units, and even housing for teachers.

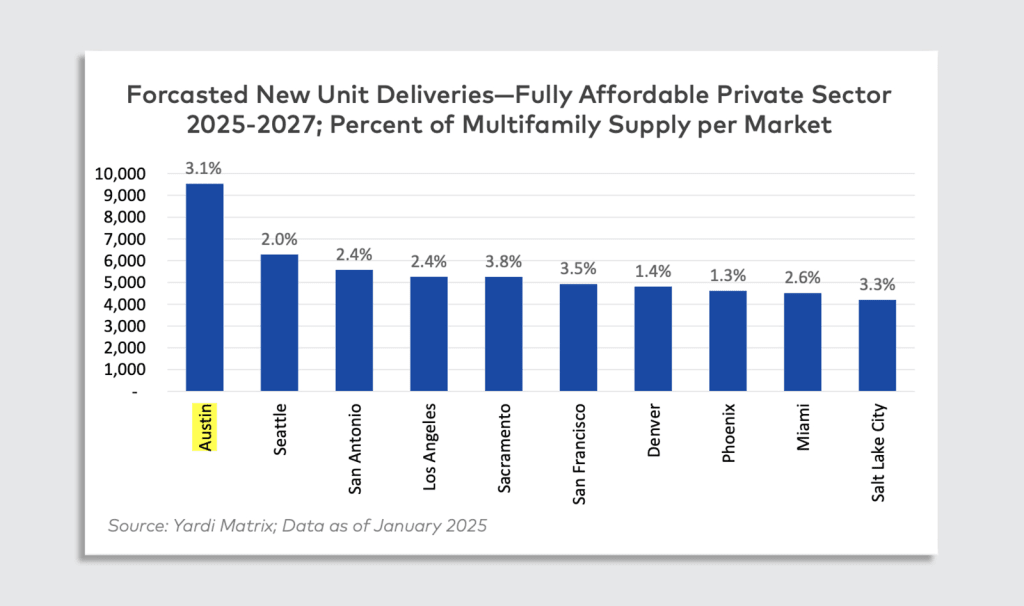

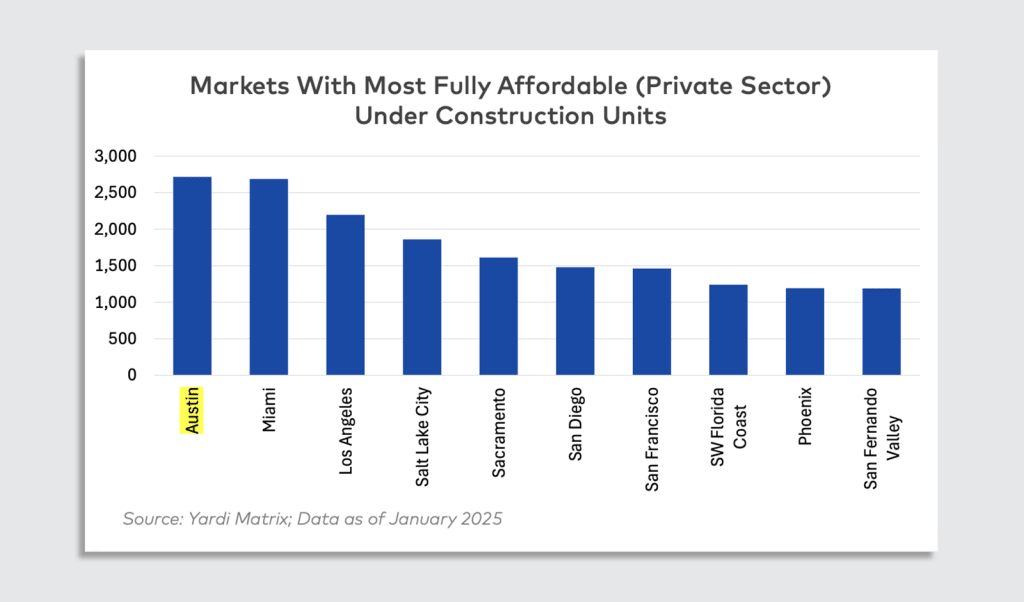

Austin’s affordable housing construction pipeline outpaces all other U.S. cities, according to research from Yardi Matrix, a real estate data source. In 2024, the city delivered 4,605 affordable units—defined as properties that agree to limit rents as a condition of a tax credit or subsidy. That’s double the rate in 2023. The research shows Austin will also deliver the most affordable units this year, 3,452—more than LA’s 2,752, despite the California city having more than four times as many people. And Austin will continue to lead, with the forecast of units in the pipeline through 2027 showing Austin with 9,528, compared to Seattle’s 6,289.

“We want to ensure that the population that made Austin what Austin is can stay in Austin,” said James May, Housing and Community Development Officer for the City of Austin Housing Department.

It’s also worth mentioning that Austin’s changing demographics are playing a large role in the housing market. As the city continues to morph from a capital and college town to a tech and healthcare nexus, wealth and median income have risen. A recent city memo noted that the city’s housing market had dramatically changed since it laid out its housing plan in the mid 2010s—median home sale price has risen by 58%, and rents went from an average of $1,350 in 2017 to a peak of $1,709 in 2022—so Austin needs to recalibrate its strategy and focus more on deeply affordable units.

“Austin used to be a city of musicians and artists, and now income and rent are far higher than what it was 10 years ago,” said Heather Way, a professor at the University of Texas-Austin who specializes in housing law.

May credited the growth in affordable housing in Austin to three factors. First, was community: Multiple providers including the city, county, housing authority, and private builders have been looking to invest in new housing, with private developers investing in significant new construction using the city’s density-bonus program.

The second was money. A series of local bonds for affordable housing raised significant funds for new construction, including a 2022 bond for $350 million, which helped fund new affordable units. In addition, the construction of new transit lines included $300 million in anti-displacement funds that also helped pay for new buildings. May said the city recently purchased a 100-acre property formerly owned by the Top Deal electronic company that it plans to use for mixed-income development, which will include affordable housing.

And finally, the third pillar was regulatory reform. The city council has passed many initiatives in recent years to increase density and make it easier to build: transit-oriented development rules allowed for higher buildings near bus and train lines, Affordability Unlocked allowed housing development on land zoned for commercial projects, and the HOME Initiative shrunk the required lot size for homes and made it legal to build multiple units on lots zoned for single-family homes.

But even with that surge, it’s still not enough. Despite Austin’s recent lead, the construction rate still lags well behind what’s actually needed to provide sufficient access to affordable housing: tens of thousands of new units would be needed to adequately meet the demand.

A record-breaking number of evictions in the surrounding county last year attest to the pressure renters feel making ends meet. And while new supply is definitely a step in the right direction, what isn’t being built is deeply affordable housing. Defined as housing that can support those making around 30% of the median income; in 2023, just 63 such units were built, even though this group makes up 17% of the city’s population.

Creating enough affordable units, and building more for those with extremely low incomes, will be even more challenging due to the changing landscape for construction. Stubbornly high interest rates will make getting financing more difficult. Tariffs will make materials more expensive. And the Trump administration’s actions against HUD, including threats to withhold funding from sanctuary cities like Austin, might end vital federal support.

“It’s going to be a tough market, we won’t see the entire pipeline go all the way through,” May said.

Austin’s boost in housing production is a start. But it’s sadly far from finished.