Platform Power Is Underrated

Platforms are so powerful that Apple's latest court loss won't change the course of the iPhone; that's why it's worth it.

— Lord Action, Letter to Bishop Creighton

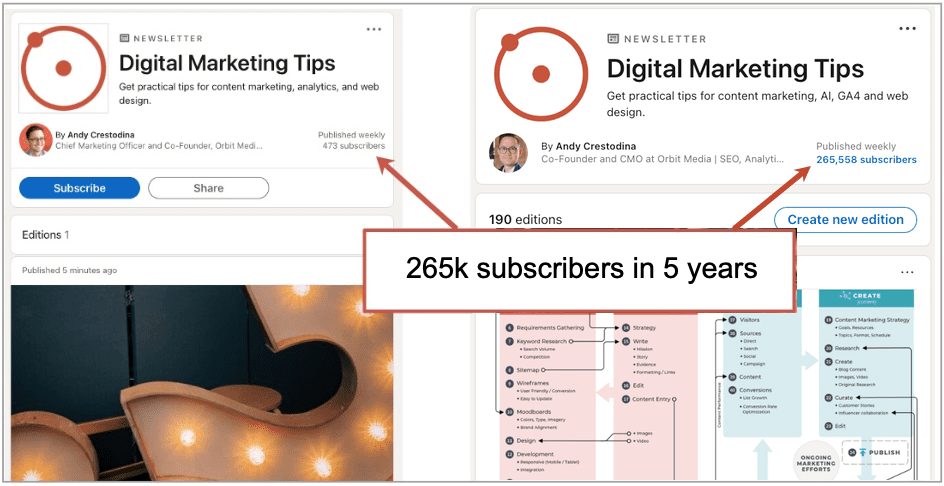

In 2015, Felix Salmon wrote about The Ingredients of a Great Newsletter, and used yours truly as an example. While that page no longer exists, the annotations Salmon made to my February 5, 2015 Update are still on Genius.

The first thing you might notice is that while the Update was from 2015, I had the wrong year in my email; I guess the positive spin is that that was due to the duct-tape-and-wire nature of my publishing system back then, but it was an embarrassing enough error that I never did link to Salmon’s piece. The reason I mention it now, however, is that while Salmon had positive thing to say about my coverage of net neutrality and Microsoft’s then-new Outlook app, he was mostly bemused by my coverage of the App Store:

Thompson is proud to have obsessions, and one of his geeky obsessions is the arcane set of rules surrounding apps in Apple’s app store. His conclusion is also a way of continuing a thread which runs through many past and future updates: as such it’s a way of rewarding loyal readers.

Again, this was 2015, not 2014, but I had indeed been obsessed with the App Store from the beginning of Stratechery; one of my earliest set of Articles was a 2013 three-piece series asking Why Doesn’t Apple Enable Sustainable Businesses on the App Store? The big change since then is that the App Store long ago stopped being a geeky obsession on Stratechery, and instead became one of the biggest stories in tech, culminating in Apple being referred to prosecutors for potential criminal contempt of court charges.

I am not writing this Article, however, to say “I told you so”; rather, what strikes me about my takes at the time, including the one that Salmon highlighted, is what I got wrong, and how much the nature of my errors bums me out.

Apple Power

The anticompetitive nature of Apple’s approach to the App Store revealed itself very early; John Gruber was writing about The App Store’s Exclusionary Policies just months after the App Store’s 2008 launch. The prompt was Apple’s decision to not approve an early podcasting app because “it duplicate[d] the functionality of the Podcast section of iTunes”; Gruber fretted:

The App Store concept has trade-offs. There are pros and cons to this model versus the wide-open nature of Mac OS X. There are reasonable arguments to be made on both sides. But blatantly anti-competitive exclusion of apps that compete with Apple’s own? There is no trade-off here. No one benefits from such a policy, not even Apple. If this is truly Apple’s policy, it’s a disaster for the platform. And if it’s not Apple’s policy, then Podcaster’s exclusion is proof that the approval process is completely broken.

Apple eventually started allowing podcast apps a year or so later (without any formal announcement), but the truth is that there wasn’t any evidence that Apple was facing any sort of disaster for the platform. Gruber himself recognized this reality two years later in an Article about Adobe’s unhappiness with the App Store:

It’s folly to pretend there aren’t trade-offs involved — that for however much is lost, squashed by Apple’s control, that different things have not been gained. Apple’s control over the App Store gives it competitive advantages. Users have a system where they can install apps with zero worries about misconfiguration or somehow doing something wrong. That Adobe and other developers benefit least from this new scenario is not Apple’s concern. Apple first, users second, developers last — those are Apple’s priorities.

Gruber has returned to this point about Apple’s priority stack regularly over the years, even as some of the company’s more egregious App Store policies seemed to benefit no one but Apple itself. Who benefits from needing to go to Amazon in the browser to buy Kindle books, or there being no “subscription” option in Netflix?1 Judge Yvonne Gonzalez Rogers argued this lack of user consideration extended to Apple’s anti-steering provision, which forbade developers from telling users about better offers on their websites, and linking to them; from Gonzalez Rogers’ original opinion:

Looking at the combination of the challenged restrictions and Apple’s justifications, and lack thereof, the Court finds that common threads run through Apple’s practices which unreasonably restrains competition and harm consumers, namely the lack of information and transparency about policies which effect consumers’ ability to find cheaper prices, increased customer service, and options regarding their purchases. Apple employs these policies so that it can extract supracompetitive commissions from this highly lucrative gaming industry. While the evidence remains thin as to other developers, the conclusion can likely be extended.

More specifically, by employing anti-steering provisions, consumers do not know what developers may be offering on their websites, including lower prices. Apple argues that consumers can provide emails to developers. However, there is no indication that consumers know that the developer does not already have the email or what the benefits are if the email was provided. For instance, Apple does not disclose that it serves as the sole source of communication for topics like refunds and other product-related issues and that direct registration through the web would also mean direct communication. Consumers do not know that if they subscribe to their favorite newspaper on the web, all the proceeds go to the newspaper, rather than the reduced amount by subscribing on the iOS device.

While some consumers may want the benefits Apple offers (e.g., one-stop shopping, centralization of and easy access to all purchases, increased security due to centralized billing), Apple actively denies them the choice. These restrictions are also distinctly different from the brick-and-mortar situations. Apple created an innovative platform but it did not disclose its rules to the average consumer. Apple has used this lack of knowledge to exploit its position. Thus, loosening the restrictions will increase competition as it will force Apple to compete on the benefits of its centralized model or it will have to change its monetization model in a way that is actually tied to the value of its intellectual property.

This all seems plausible, and, thanks to Judge Gonzalez Rogers’ latest ruling, is set to be tested in a major way: apps like Spotify have already been updated to inform users about offers on their websites, complete with external links. Moreover, those links don’t have to follow Apple’s proposed link entitlement rules, which means they can be tokenized to the app user, facilitating a fairly seamless checkout experience, without the need to login separately.

Still, there are strong arguments to be made that many apps may be disappointed in their web purchase experience; Apple’s in-app purchase flow is so seamless and integrated — and critically, linked to an up-to-date payment method — that it will almost certainly convert better than web-based flows. At the same time, a 30% margin difference is a strong incentive to close that gap; the 15% margin difference for subscriptions is smaller, but at the same time, the payoffs from a web-based subscription — no Apple tax for the entire lifetime of the user — are so significant that the incentives might even be stronger.

Those incentives are likely to accrue to users: Spotify could, for example, experiment with offering some number of months free, or lower prices for a year, or just straight up lower prices overall; this is in addition to the ability to offer obvious products that have previously been impossible, like individual e-books. This is good for users, and it’s good for Spotify.

What is notable — and what I got wrong all those years ago — is the extent to which this is an unequivocally bad thing for Apple. They will, most obviously, earn less App Store revenue than they might have otherwise; while not every purchase on the web is one not made in the App Store — see previously impossible products, like individual e-books — the vast majority of web-based revenue earned by app makers will be a direct substitute for revenue Apple previously took a 15–30% cut of. Apple could, of course, lower their take rate, but that makes the point!

At the same time, I highly doubt that web-based purchases will lead to any increase in Apple selling more iPhones (they might, however, sell more advertising). This is the inverse of Gruber’s long-ago concern about Apple’s policies being “a disaster for the platform”, or my insistence that the company’s policies were “unsustainable”. In fact, they were quite sustainable, and extremely profitable.

The Chicken-and-Egg Problem

Before I started Stratechery, I worked at Microsoft recruiting developers for the Windows App Store; the discussion then was about the “chicken-and-egg problem” of building out a new platform: to get users you needed apps, but to get developers to build those apps you needed users that they wished to reach. Microsoft tried to cold-start this conundrum on the only side where they had a hope of exerting influence, which was developers: this meant lots of incentives for app makers, up-to-and-including straight up paying them to build for the platform.

This made no difference at all: most developers said no, cognizant that the true cost of building an app for a new platform was the ongoing maintenance of said app for a limited number of people, and those that said yes put forth minimal effort. Even if they had built the world’s greatest apps, however, I don’t think it would have mattered.

The reality is that platforms are not chicken-and-egg problems: it is very clear what comes first, and that is users. Once there are users there is demand for applications, and that is the only thing that incentivizes developers to build. Moreover, that incentive is so strong that it really doesn’t matter how many obstacles need to be overcome to reach those users: that is why Apple’s longstanding App Store policies, egregious though they may have been, ultimately did nothing to prevent the iPhone from having a full complement of apps, and, by extension, did nothing to diminish the attractiveness of the iPhone to end users.

Indeed, you could imagine a counterfactual where another judge in another universe decided that Apple should actually lock down the App Store even further, and charge an even higher commission: I actually think that this would have no meaningful difference on the perceived number of apps or on overall iPhone sales. Sure, developers would suffer, and some number of apps would prove to be unviable or, particularly in the case of apps that depend on advertising for downloads, less successful given their decreased ROAS, but the market is so large and liquid that the overall user experience and perceived value of apps would be largely the same.

This stark reality does, perhaps surprisingly, give me some amount of sympathy for Apple’s App Store intransigence. The fact of the matter is that everyone demanding more leniency in the App Store, whether that be in terms of commission rates or steering provisions or anything else, are appealing to nothing more than Apple’s potential generosity. The company’s self interest — and fiduciary duty to shareholders — has been 100% on the side of keeping the App Store locked down and commissions high.

Products → Platforms

That, by extension, is what bums me out about this entire affair. I would prefer to live in the tech world I and so many others mythologize, where platforms enable developers to make new apps, with those apps driving value to the underlying platform and making it even more attractive and profitable. That is what happened with the PC, and the creation of applications like VisiCalc and Photoshop.

That was also a much smaller market than today. VisiCalc came out in 1979, when 40,000–50,000 computers were sold; Photoshop launched on the Mac in 1990, with an addressable market of around a million Macs. The Vision Pro, meanwhile, is a flop for having sold only 500,000 units in 2024, nowhere near enough to attract a killer app, even if Apple’s App Store policies were not a hindrance.

None other than Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg seems to recognize this new reality; one of my longest running critiques of Zuckerberg has been his continual obsession with building a platform a la Bill Gates and Windows, but as he told me last week, that’s not necessarily the primary goal now, even for Oculus devices:

If you continue to deliver on [value] long term, is it still okay if that long term doesn’t include a platform, if you’re just an app?

MZ: It depends on what you’re saying. I think early on, I really looked up to Microsoft and I think that that shaped my thinking that, “Okay, building a developer platform is really cool”.

It is cool.

MZ: Yeah, but it’s not really the kind of company fundamentally that we have been historically. At this point, I actually see the tension between being primarily a consumer company and primarily a developer company, so I’m less focused on that at this point.

Now, obviously we do have developer surfaces in terms of all the stuff in Reality Labs, our developer platforms. We need to empower developers to build the content to make the devices good. The Llama stuff, we obviously want to empower people to use that and get as much of the world on open source as possible because that has this virtuous flywheel of effects that make it so that the more developers that are using Llama, the more Nvidia optimizes for Llama, the more that makes all our stuff better and drives costs down, because people are just designing stuff to work well with our systems and making their efficiency improvements to that. So, that’s all good.

But I guess the thing that I really care about at this point is just building the best stuff and the way to do that, I think, is by doing more vertical integration. When I think about why do I want to build glasses in the future, it’s not primarily to have a developer platform, it’s because I think that this is going to be the hardware platform that delivers the best ability to create this feeling of presence and the ultimate sense of technology delivering a social connection and I think glasses are going to be the best form factor for delivering AI because with glasses, you can let your AI assistant see what you see and hear what you hear and talk in your ear throughout the day, you can whisper to it or whatever. It’s just hard to imagine a better form factor for something that you want to be a personal AI that kind of has all the context about your life.

The great irony of Zuckerberg’s evolution — which he has been resisting for over a decade — is that this actually makes it more likely he will get a platform in the end. It seems clear in retrospect that DOS/Windows was the exception, not the rule; platforms, at least when it comes to the consumer space, are symptoms of products that move the needle. The only way to be a platform company is to be a product company first, and acquire the users that incentivize developers.

Takings and the Public Interest

Notice, however, the implication of this reality: an honest accounting of modern platforms, including iOS, is not simply that Apple, or whoever the platform provider is, owns intellectual property for which they have a right to be compensated; as I noted on Friday Apple has a viable appeal predicated on arguing Judge Gonzalez Rogers is “taking” their IP without compensation. What they actually own that is of the most value is user demand itself; to put it another way, Apple could charge a high commission and have stringent rules because developers wanted to be on their platform regardless. Demand draws supply, no matter the barriers.

This, in the end, is the oddity of this case, and the true “takings” violation: what is actually being taken from Apple is simply money. I don’t think anything is going to change about iPhone sales or app maker motivation; the former will simply be less profitable, and the latter more so. Small wonder Apple has fought to keep its position so strenuously!

This also leaves me more conflicted about Judge Gonzalez Rogers’ decision than I expected: I don’t like depriving Apple of their earned rewards, or diminishing the incentive to pursue this most difficult of goals — building a viable platform — in any way. Yes, Apple has made tons of money on the App Store, but the iPhone and associated ecosystem is of tremendous value.

At the same time, everything is a trade-off, and the fact that products that produce demand are the key to creating platforms significantly increases the public interest in regulating platform policies. I don’t think it is to society’s benefit to effectively delegate all innovation to platform providers, given how few there inevitably are; what needs incentivizing is experimentation on top of platforms, and that means recognizing that modern platform providers are in fact incentivized to tax that out of existence.

In fact you could, from a business perspective, make the case that Microsoft’s biggest mistake with Windows, at least from a shareholder perspective, was actually not harvesting as much value as they should have: two-sided network effects are so powerful that, once established, you can skim off as much money as you want with no ill effects. Apple certainly showed that was the case with the iPhone, and Google followed them; Meta has similar policies for Oculus.

To that end, Congress should be prepared to act if Judge Gonzalez Rogers’ order is overturned on appeal; in fact, they should act anyways. My proposed law is clear and succinct:

- A platform is a product with an API that runs 3rd-party applications.

- A platform has 25 million+ U.S. users.

- 3rd-party applications should have the right, but not the compulsion, to (1) conduct commerce as they choose and (2) publish speech as they choose.

That’s it! If you want the benefit of 3rd-party applications (which are real — there’s an app for that!) then you have to offer fundamental economic and political freedom. This is in the American interest for the exact same reason that this wouldn’t kill the incentive to build the sort of product that leads to a platforms in the first place: platforms are so powerful that everyone in tech has, for decades, been both obsessed with them even as they underrated them.

You can subscribe to Netflix using the App Store by downloading one of Netflix’s games. ↩