Checking In on AI and the Big Five

A review of the current state of AI through the lens of the Big Five tech companies.

This is how I opened January 2023’s AI and the Big Five:

The story of 2022 was the emergence of AI, first with image generation models, including DALL-E, MidJourney, and the open source Stable Diffusion, and then ChatGPT, the first text-generation model to break through in a major way. It seems clear to me that this is a new epoch in technology.

Sometimes the accuracy of a statement is measured by its banality, and that certainly seems to be the case here: AI is the new epoch, consuming the mindshare of not just Stratechery but also the company’s I cover. To that end, two-and-a-half years on, I thought it would be useful to revisit that 2023 analysis and re-evaluate the state of AI’s biggest players, primarily through the lens of the Big Five: Apple, Google, Meta, Microsoft, and Amazon.

The proximate cause for this reevaluation is the apparent five alarm fire that is happening at Meta: the company’s latest Llama 4 release was disappointing — and in at least one case, deceptive — pushing founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg to go on a major spending spree for talent. From The Wall Street Journal over the weekend:

Mark Zuckerberg is spending his days firing off emails and WhatsApp messages to the sharpest minds in artificial intelligence in a frenzied effort to play catch-up. He has personally reached out to hundreds of researchers, scientists, infrastructure engineers, product stars and entrepreneurs to try to get them to join a new Superintelligence lab he’s putting together…And Meta’s chief executive isn’t just sending them cold emails. Zuckerberg is also offering hundreds of millions of dollars, sums of money that would make them some of the most expensive hires the tech industry has ever seen. In at least one case, he discussed buying a startup outright.

While the financial incentives have been mouthwatering, some potential candidates have been hesitant to join Meta Platforms’ efforts because of the challenges that its AI efforts have faced this year, as well as a series of restructures that have left prospects uncertain about who is in charge of what, people familiar with their views said. Meta’s struggles to develop cutting-edge artificial-intelligence technology reached a head in April, when critics accused the company of gaming a leaderboard to make a recently released AI model look better than it was. They also delayed the unveiling of a new, flagship AI model, raising questions about the company’s ability to continue advancing quickly in an industrywide AI arms race…

For those who have turned him down, Zuckerberg’s stated vision for his new AI superteam was also a concern. He has tasked the team, which will consist of about 50 people, with achieving tremendous advances with AI models, including reaching a point of “superintelligence.” Some found the concept vague or without a specific enough execution plan beyond the hiring blitz, the people said.

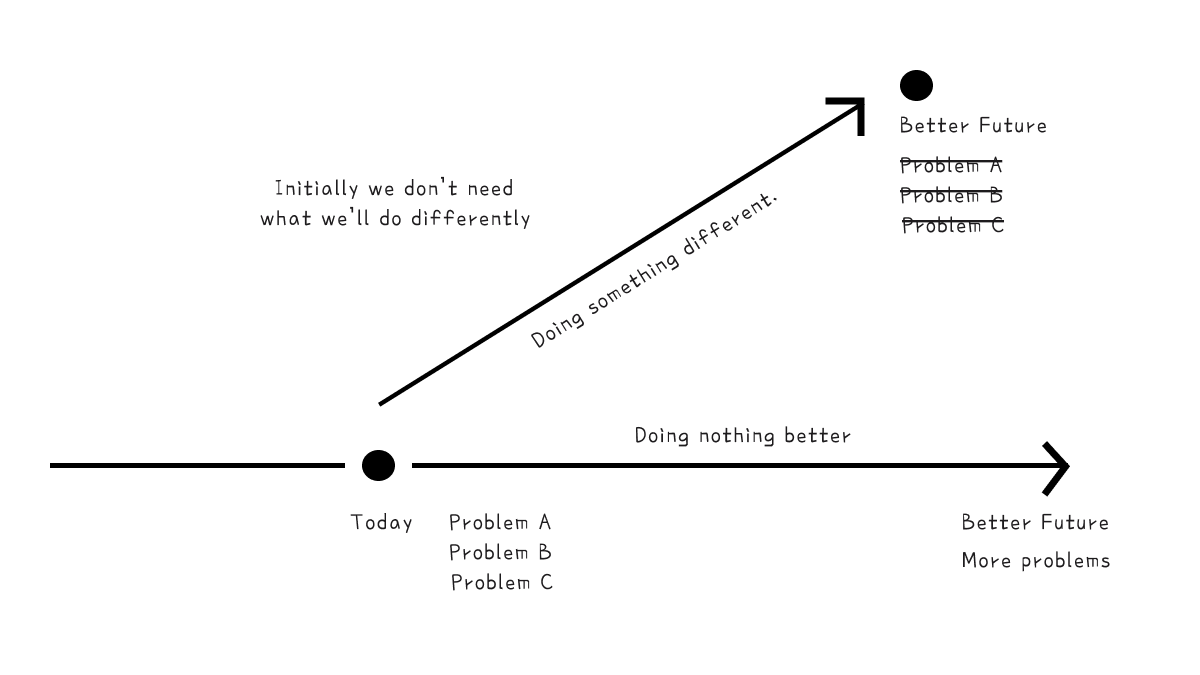

That last paragraph complicates analysis generally. In my January 2023 Article I framed my evaluation through Professor Clay Christensen’s framework of sustaining versus disruptive innovation: was AI complementary to existing business models (i.e. Apple devices are better with AI) or disruptive to them (i.e. AI might be better than Search but monetize worse). A higher level question, however, is if AI simply obsoletes everything, from tech business models to all white collar work to work generally or even to life itself.

Perhaps it is the smallness of my imagination or my appreciation of the human condition that makes me more optimistic than many about the probability of the most dire of predictions: I think they are quite low. At the same time, I think that those dismissing AI as nothing but hype are missing the boat as well. This is a big deal, even if the changes may end up fitting into the Bill Gates maxim that “We always overestimate the change that will occur in the next two years and underestimate the change that will occur in the next ten.”

To that end, let’s go back two years to AI and the Big Five, and consider where we might be in eight.

Apple

Infrastructure: Minimal

Model: None

Partner: OpenAI?

Data: No public data differentiation, potential private data differentiation

Distribution: Apple devices

Core Business: Devices are complementary to current AI use cases

Scarcity Risk: Could lose differentiation in high-end hardware

Disruptive/Sustaining: Sustaining

New Business Potential: Robotics

Apple has had a dramatic few years marked by the debacle that has been Apple Intelligence: the company has basic on-device LLM capabilities and its own private cloud compute infrastructure, but is nowhere near the cutting edge in terms of either models or products.

The company’s saving grace, however, is that its core business is not immediately threatened by AI. OpenAI, Claude, etc. are, from a consumer perspective, apps that you use on your iPhone or in a browser; Cursor is an IDE you use on your Mac. Apple’s local LLMs, meanwhile, can potentially differentiate apps built for Apple platforms, and Apple has unique access to consumer data and, by extension, the means to build actually usable and scalable individual semantic indexes over which AI can operate.

This positioning isn’t a panacea; in April’s Apple and the Ghosts of Companies Past, I analogized Apple’s current position to Microsoft and the Internet: everyone used the Internet on Windows PCs, but it was the Internet that created the conditions for the paradigm that would surpass the PC, which was mobile.

What Microsoft did that Intel — another company I compared Apple to — did not, was respond to their mobile miss by accepting their loss, building a complementary business (cloud computing), which then positioned them for the AI paradigm. Apple should do something similar: I am very encouraged by the company’s deepening partnership with OpenAI in iOS 26, and the company should double-down on being the best hardware for what appears to be the dominant consumer AI company.

The way this leads to a Microsoft-like future is by putting the company’s efforts towards building hardware beyond the phone. Yes, OpenAI has acqui-hired Jony Ive and his team of Apple operational geniuses, but Apple should take that as a challenge to provide OpenAI with better hardware and bigger scale than the horizontal services company can build on their own. That should mean a host of AI-powered devices beyond the phone, including the Apple Watch, HomePod, glasses, etc.; in the long run Apple should be heavily investing in robotics and home automation. There is still no one better at consumer hardware than Apple, both in terms of quality and also scalability, and they should double down on that capability.

The biggest obstacle to this approach is Apple’s core conception of itself as an integrated hardware and software maker; the company’s hardware is traditionally differentiated by the fact it runs Apple’s own software, and, for many years, it was the software that sold the devices. In truth, however, Apple’s differentiation has been shifting from software to hardware for years now, and while Apple’s chips have the potential to offer the best local AI capabilities, those local capabilities will be that much more attractive if they are seamlessly augmented by state-of-the-art cloud AI capabilities.

If Apple does feel the need to go it alone, then the company needs to make a major acquisition and commit to spending billions of dollars. The best option would be Mistral: the company has a lot of talent (including a large portion of the team that built Meta’s early and well-regarded Llama models), and its open source approach is complementary to Apple’s business. It’s unclear, however, if French and European authorities would allow the current jewel of the European startup ecosystem to be acquired by an American company; regardless, Apple needs to either commit to partnering — and the loss of control that entails — or commit to spending a lot more money than they have to date.

Infrastructure: Best

Model: Good

Partner: None

Data: Best

Distribution: Android devices, Search, GCP

Core Business: Chatbots are disruptive to Search

Scarcity Risk: Data feedback loops diminished

Disruptive/Sustaining: Disruptive

New Business Potential: Cloud

Google is in many respects the opposite of Apple: the search company’s last two years have gone better than I anticipated (while Apple’s have gone worse), but their fundamental position and concerns remain mostly unchanged (in Apple’s case, that’s a good thing; for Google it’s a concern).

Google’s infrastructure is in many respects the best in the world, and by a significant margin. The company is fully integrated from chips to networking to models, and regularly points to that integration as the key to unlocking capabilities like Gemini’s industry-leading context window size; Gemini also has the most attractive pricing of any leading AI model. On the other hand, integration can have downsides: Google’s dependence on its own TPUs means that the company is competing with the Nvidia ecosystem up-and-down the stack; this is good for direct cost savings, but could be incurring hidden costs in terms of tooling and access to innovations.

Gemini, meanwhile, has rapidly improved, and scores very highly in LLM evaluations. There is some question as to whether or not the various model permutations are over-indexed on those LLM valuations; real world usage of Gemini seems to significantly lag behind OpenAI and Anthropic’s respective models. Where Google is undoubtedly ahead is in adjacent areas like media generation; Veo in particular appears to have no peers when it comes to video generation.

This speaks to what might be Google’s most important advantage: data. Veo can draw on YouTube video, the scale of which is hard to fathom. Google’s LLMs, meanwhile, benefit not only from Google’s leading position in terms of indexing the web, but also the fact that no website can afford to block Google’s crawler. Google has also spent years collecting other forms of data, like scanning books, archiving research papers, etc.

Google also has distribution channels, particularly Android: the potential to deliver an integrated device and cloud AI experience is compelling, and is Android’s best chance yet to challenge Apple’s dominance of the high end. Delivering on that integration will be key, however: ChatGPT dominates consumer mindshare to-date, and, as I noted above, Apple can and should differentiate itself as the best devices for using ChatGPT; can Google make its devices better by controlling both the model and the operating system (and access to all of the individual consumer data that entails)? Or, to put it another way, can Google actually make a good product?

The problem for Google, just as one could foresee two years ago (and even years before then), is the disruptive potential of AI for its core business of Search. The problem with having a near perfect business model — which is what Google had with Search ads where users picked the winner of an auction — is that there is nowhere to go but down. Given that, I think that Google has done well with its focus on AI Search Overviews to make Search better and, at least so far, maintain monetization rates; I also think the company’s development of the Search Funnel to systemically evolve search for AI is a smart approach to tilt AI from being disruptive to sustaining.

What is much more promising is cloud computing, which is where Google’s infrastructure and model advantages (particularly in terms of pricing) can truly be brought to bear, without the overhand of needing to preserve revenue or reignite sclerotic product capabilities. Google Cloud Platform has been very focused on fitting into multi-cloud workflows, but the big potential in the long run is that Google’s AI capabilities act as gravity for an ever increasing share of enterprise cloud workflows generally.

Meta

Infrastructure: Good

Model: OK

Partner: None

Data: Good

Distribution: Meta apps, Quest devices

Core Business: AI delivers more individualized content and ads

Scarcity Risk: Attention diverted to chatbots

Disruptive/Sustaining: Sustaining

New Business Potential: Virtual worlds and generative UIs

Meta’s positioning is somewhere between Apple and Google, but I’ve assumed it was closer to the former; the company may be scuffling more than expected in AI, but its core strategic positioning seems more solid: more individualized content slots into Meta’s distribution channels, and generative ads should enhance Meta’s offering for its long tail advertising base. Generative AI, meanwhile, is very likely the key to Meta realizing a return on its XR investments, both by creating metaverses for VR and UI for AR. I’m on the record as being extremely optimistic about Meta’s AI Abundance.

There are risks, however. The scarce resource Meta competes for is attention, and LLMs are already consuming huge amounts of it and expanding all the time. There is an argument that this makes chatbots just as much of a problem for Meta as they are for Google: even if Meta gets lots of users using Meta AI, time spent using Meta AI is time not spent consuming formats that are better suited to monetization. The difference is that I think that Meta would do a better job of monetizing those new surfaces: there is no expectation of objectivity or reliability to maintain like there is with search; sometimes being a lowest common denominator interface is an asset.

That noted, what does seem clear from Zuckerberg’s spending spree is that these risks are probably bigger than I appreciated. While Zuckerberg has demonstrated with the company’s Reality Labs division that he is willling to invest billions of dollars in an uncertain future, the seeming speed and desperation with these AI recruiting efforts strongly suggests that the company’s core business is threatened in ways I didn’t properly appreciate or foresee two years ago. In retrospect, however, that makes sense: the fact that there are so many upside scenarios for Meta with AI by definition means there is a lot of downwide embedded in not getting AI right; the core business of a company like Apple, on the other hand, is sufficiently removed from AI that both its upside and downside are more limited, relatively speaking.

What does concern me is the extent to which Meta seems to lack direction with AI; that was my biggest takeaway from my last interview with Zuckerberg. I felt like I had more ideas for how generative AI could impact the company’s business than Zuckerberg did (Zuckerberg’s comments on the company’s recent earnings call were clearly evolved based on our interview, which took place two days prior); that too fits with the current frenzy. Zuckerberg seems to have belatedly realized not only that the company’s models are falling behind, but that the overall AI effort needs new leadership and new product thinking; thus Alexandr Wang for knowledge on the state of the art, Nat Friedman for team management, and Daniel Gross for product. It’s not totally clear how this team will be organized or function, but what is notable — and impressive, frankly — is the extent to which Zuckerberg is implicitly admitting he has a problem. That’s the sort of humility and bias towards action that Apple could use.

Microsoft

Infrastructure: Very Good

Model: None

Partner: OpenAI

Data: Good

Distribution: Windows, Microsoft 365, Azure

Core Business: AI drives Azure usage

Scarcity Risk: Access to leading edge models

Disruptive/Sustaining: Sustaining for Azure, potentially disruptive for Microsoft 365

New Business Potential: Agents

Microsoft’s position seemed unimpeachable in January 2023; this is the entirety of what wrote in AI and the Big Five:

Microsoft, meanwhile, seems the best placed of all. Like AWS it has a cloud service that sells GPUs; it is also the exclusive cloud provider for OpenAI. Yes, that is incredibly expensive, but given that OpenAI appears to have the inside track to being the AI epoch’s addition to this list of top tech companies, that means that Microsoft is investing in the infrastructure of that epoch.

Bing, meanwhile, is like the Mac on the eve of the iPhone: yes it contributes a fair bit of revenue, but a fraction of the dominant player, and a relatively immaterial amount in the context of Microsoft as a whole. If incorporating ChatGPT-like results into Bing risks the business model for the opportunity to gain massive market share, that is a bet well worth making.

The latest report from The Information, meanwhile, is that GPT is eventually coming to Microsoft’s productivity apps. The trick will be to imitate the success of AI-coding tool GitHub Copilot (which is built on GPT), which figured out how to be a help instead of a nuisance (i.e. don’t be Clippy!).

What is important is that adding on new functionality — perhaps for a fee — fits perfectly with Microsoft’s subscription business model. It is notable that the company once thought of as a poster child for victims of disruption will, in the full recounting, not just be born of disruption, but be well-placed to reach greater heights because of it.

Microsoft is still well-positioned, but things are a bit more tenuous than what I wrote in that Article:

- Microsoft’s relationship with OpenAI is increasingly frayed, most recently devolving into OpenAI threats of antitrust complaints if Microsoft doesn’t relinquish its rights to future profits and agree to OpenAI’s proposed for-profit restructuring. My read of the situation is that Microsoft still has most of the leverage in the relationship — thus the threats of government involvement — but only until 2030 when the current deal expires.

- Bing provided the remarkable Sydney, which Microsoft promptly nerfed; relatedly, Bing appears to have gained little if any ground thanks to its incorporation of AI.

- GitHub Copilot has been surpassed by startups like Cursor and dedicated offerings from foundation model makers, while the lack of usage and monetization numbers for Microsoft’s other Copilot products are perhaps telling in their absence.

- The extent that AI replaces knowledge workers is the extent to which the Microsoft 365 franchise, like all subscription-as-a-service businesses, could be disrupted.

What is critical — and why I am still bullish on Microsoft’s positioning — is the company’s infrastructure and distribution advantages. I already referenced the company’s pivot after missing mobile: the payoff to The End of Windows was that the company was positioned to capitalize on AI when the opportunity presented itself in a way that Intel was not. Microsoft also, by being relatively late, is the most Nvidia-centric of the hyperscalers; Google is deeply invested in TPUs (although they offer Nvidia instances), while Amazon’s infrastructure is optimized for commodity computing (and is doubling down with Trainium).

Azure, meanwhile, is the exclusive non-OpenAI provider of OpenAI APIs, which not only keeps Microsoft enterprise customers on Azure, but is also a draw in their own right. To that end, I think that Microsoft’s priority in their negotiations with OpenAI should be on securing this advantage for Azure permanently, even if that means giving up many of their rights to OpenAI’s business as a whole.

The other thing that Microsoft should do is deepen their relationship — and scale of investment — in alternative model providers. It was a good sign that xAI CEO Elon Musk appeared in a pre-recorded video at Microsoft Build; Microsoft should follow that up with an investment in helping ensure that xAI continues to pursue the leading edge of AI models. Microsoft has also made small-scale investments in Mistral and should consider helping fund Llama; these sorts of investments are expensive, but not having access to leading models — or risking total dependency on Sam Altman’s whims — would be even pricier.

Amazon

Infrastructure: Good

Model: Poor

Partner: Anthropic

Data: Good

Distribution: AWS, Alexa

Core Business: AI drives AWS usage

Scarcity Risk: Access to leading edge models, chip competitiveness

Disruptive/Sustaining: Sustaining for AWS, long tail e-commerce recommendations potentially disruptive for Amazon.com

New Business Potential: Agents, Affiliate revenue from AI recommendations on Amazon.com

I’ve become much more optimistic about Amazon’s position over the last two years:

- First, there is the fact that AI is not disruptive for any of Amazon’s businesses; if anything, they all benefit. Increased AWS usage is obvious, but also Amazon.com could be a huge beneficiary of customers using AI for product recommendations (on the other hand, AI could be more effective at finding and driving long tail e-commerce alternatives, or reducing the importance of Amazon.com advertising). AWS is also primarily monetized via usage, not seats; to the extent AWS-based seat-driven SaaS companies are disrupted is the extent to which AWS will probably earn more usage revenue from AI-based disruptors.

- Second, AWS’s partnership with Anthropic also seems much more stable than Microsoft’s partnership with OpenAI. ChatGPT obviously drives a ton of Azure usage, but it’s also the core reason why OpenAI and Microsoft’s conflict was inevitable; Anthropic’s lack of a strong consumer play means it is much more tenable, if not downright attractive, for them to have a supplier-type of relationship with AWS, up-to-and-including building for AWS’s Trainium architecture. And, in the long run, even the upside Anthropic scenario, where they have a compelling agent enterprise business, is compatible with AWS, which acts as infrastructure for many successful platform companies.

- Third, AWS’s early investment in Bedrock was an early bet on AI optionality; the company’s investment in Trainium provides similar benefits in terms of the future of AI chips. You could certainly make the case that Amazon was and is behind in terms of core model offerings and chip infrastructure; that exact same case could be spun as Amazon being the best placed to shift as the future AI landscape becomes clearer over time.

AWS, meanwhile, remains the largest cloud provider by a significant margin, and, at the end of the day, enterprises would prefer to use the AI that is close to their existing data rather than to go through the trouble of a migration. And don’t forget about Alexa: there is, as I expected, precious little evidence of Alexa+ even being available, much less living up to its promise, but there is obviously more potential than ever in voice-controlled devices.

The Model Makers

The foundation model makers are obviously critical to AI; while this Article is focused on the Big Tech companies, it’s worth checking in on the status of the makers of the underlying technology:

OpenAI: I have long viewed OpenAI as the accidental consumer tech company; I think this lens is critical to understanding much of the last two years. A lot of OpenAI’s internal upheaval, for example, may in part stem from conflict with CEO Sam Altman, but it’s also the fact that early OpenAI employees signed up for a science project, not to be the next Facebook.

I do think that ChatGPT has won the consumer AI space, and is more likely to extend its dominance than to be supplanted. This, by extension, puts OpenAI fundamentally at conflict with any other entity that seeks to own the customer relationship, from Microsoft to Apple. Both companies, however, may have no choice but to make it work: Microsoft, because they’re already in too deep, and Apple, because OpenAI may, sooner rather than later, be the most compelling reason to buy the iPhone (if Apple continues to deepen its integration).

The big question in my mind is when and if OpenAI figures out an advertising model to supplement its subscription business. While I — and most of you reading this — will gladly pay for AI’s productivity gains, the fact remains that huge swathes of the consumer space likely won’t, and owning that segment not only locks out rivals, but also gives a long-term advantage in terms of revenue and the ability to invest in future models.

Anthropic: Anthropic may have missed out on the consumer space, but the company’s focus on coding has paid off in a very strong position with developers and a big API revenue stream. This is a riskier position in some respects, since developers and intermediaries like Cursor can easily switch to other models that might one day be better, but Anthropic is seeking to ameliorate that risk with products like Code that can not only be a business in its own right, but also generate critical data for improving the underlying model.

Anthropic’s reliance on Amazon and its Trainium chips for training is potentially suboptimal; it also could mean meaningful cost savings in the long run. Most importantly, however, Amazon is now a deeply committed partner for Anthropic; as I noted above, this is likely a much stabler situation than Microsoft and OpenAI.

Anthropic, unlike OpenAI, also benefits from its longer-term business opportunity being more aligned with the AGI dreams of its leading researchers: the latter might not create God, but if they manage to come up with an autonomous agent service along the way there will be a lot of money to be made.

xAI: I wrote more about xAI’s tenuous position last week; briefly:

- xAI’s insistence on owning its own infrastructure seems to me to be more of a liability than an asset. Yes, Elon Musk can move more quickly on his own, but spending a lot of money on capital expenditures that aren’t fully utilized because of a lack of customers is an excellent way to lose astronomical amounts of money.

- xAI is a company that everyone wants to exist as an alternative to keep OpenAI and Anthropic honest, but that doesn’t pay the bills. This is why the company should aggressively seek investment from Microsoft in particular.

- There is an angle where xAI and Oracle make sense as partners: xAI could use an infrastructure partner, and Oracle could use a differentiated AI offering. The problem is that they could simply exacerbate each others challenges in terms of acquiring customers.

One of the most harmful things that has happened to xAI is the acquisition of X; that simply makes xAI a less attractive investment for most companies, and an impossible acquisition target for Meta, which is clearly willing to pay for xAI’s talent. What is more interesting is the relationship with Tesla; to the extent that the bitter lesson covers self-driving is the extent that xAI’s infrastructure can, at worst, simply be productively funneled to another Musk company.

Meta: Here we are full circle with the news of the week. There is a case to be made that Meta is simply wasting money on AI: the company doesn’t have a hyperscaler business, and benefits from AI all the same. Lots of ChatGPT-generated Studio Ghibli pictures, for example, were posted on Meta properties, to Meta’s benefit.

The problem for Meta — or anyone else who isn’t a model maker — is that the question of LLM-based AI’s ultimate capabilities is still subject to such fierce debate. Zuckerberg needs to hold out the promise of superIntelligence not only to attract talent, but because if such a goal is attainable then whoever can build it won’t want to share; if it turns out that LLM-based AIs are more along the lines of the microprocessor — essential empowering technology, but not a self-contained destroyer of worlds — then that would both be better for Meta’s business and also mean that they wouldn’t need to invest in building their own. Unfortunately for Zuckerberg, waiting-and-seeing means waiting-and-hoping, because if the bet is wrong Meta is MySpace.

This is also where it’s important to mention the elephant in the room: China. Much of the U.S. approach to China is predicated on the assumption that AI is that destroyer of worlds and therefore it’s worth risking U.S. technological dominance in chips to stop the country’s rise, but that is a view with serious logical flaws. What may end up happening — and DeepSeek pointed in this direction — is that China ends up commoditizing both chips and AI; if that happened it’s Big Tech that would benefit the most (to Nvidia’s detriment), and it wouldn’t be the first time.

![Building A Digital PR Strategy: 10 Essential Steps for Beginners [With Examples]](https://buzzsumo.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Building-A-Digital-PR-Strategy-10-Essential-Steps-for-Beginners-With-Examples-bblog-masthead.jpg)