In Las Vegas, a former SpaceX engineer is pulling CO2 from the air to make concrete

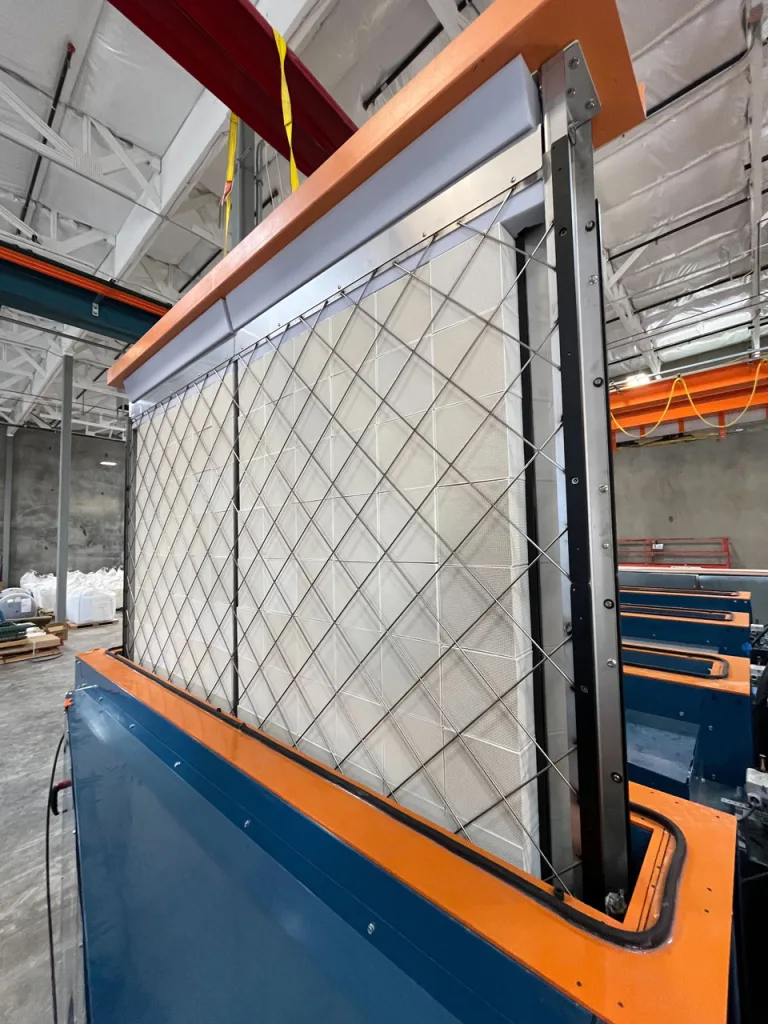

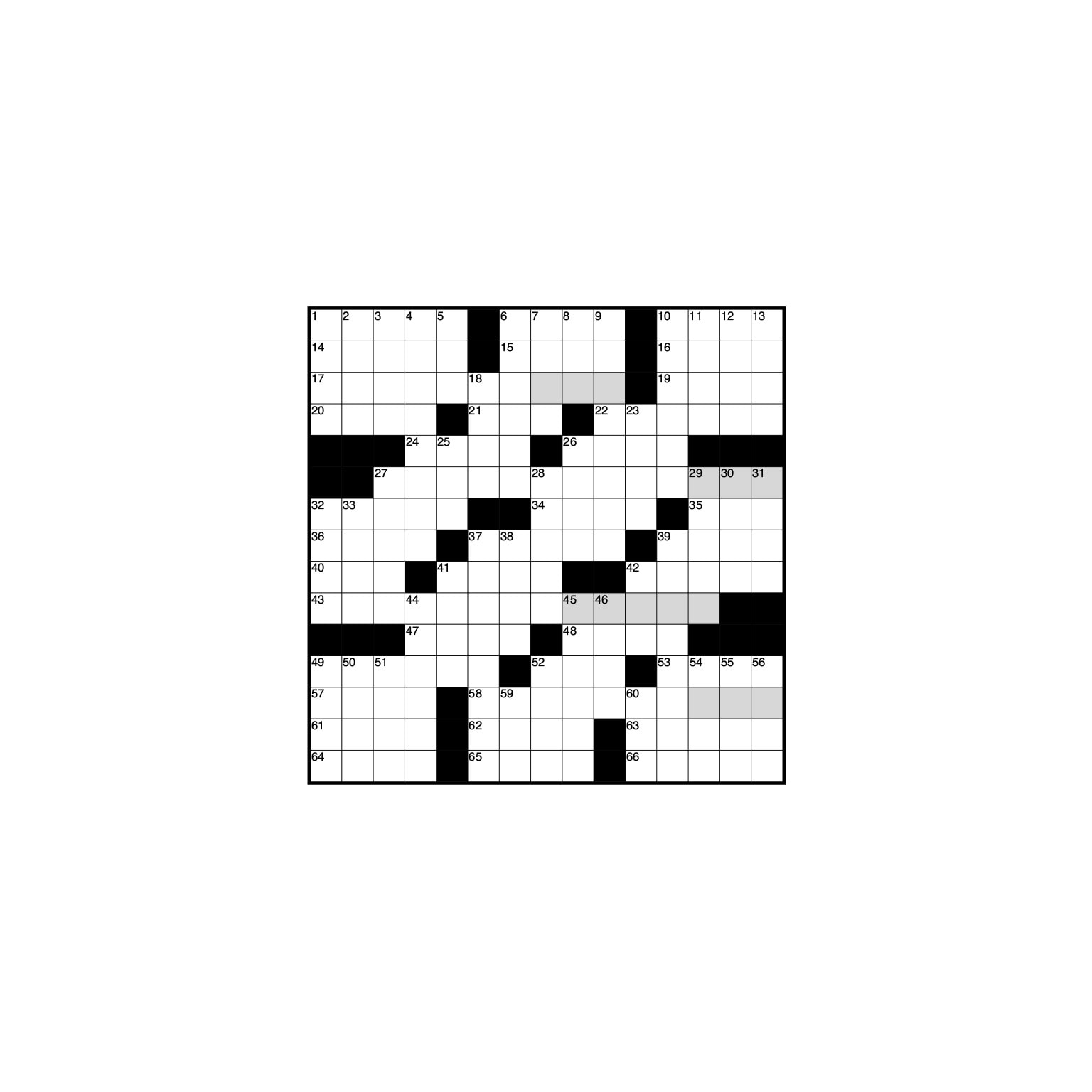

In an industrial park in North Las Vegas, near an Amazon warehouse and a waste storage facility, a new carbon removal plant is beginning to pull CO2 from the air and store it permanently. Called Project Juniper, it’s the first “integrated” plant of its kind in the U.S., meaning that it handles both carbon capture and storage in one place. (As a bonus, it also generates clean water.) Clairity Tech, the startup behind it, designed the new plant after raising a seed round of funding led by Initialized Capital and Lowercarbon Capital last year. After spending the last few months setting up the facility, it ran its full system for the first time last week. Founder Glen Meyerowitz, who previously worked on rocket and spacecraft propulsion testing at SpaceX, pivoted to carbon removal in 2022. “As I look at it, this is really the existential threat of our time and the most important problem that needs to be addressed,” he says. In order for the world to have any chance of meeting climate goals, CO2 needs to be captured from the air at a massive scale at the same time as the economy decarbonizes. As Meyerowitz researched the space, he saw an opportunity to take a slightly different approach than some other companies. The Clairity direct air capture reactor in Nevada [Photo: Clairity] First, Clairity uses a different material to capture CO2 from the air. “It’s in the same family as baking soda,” Meyerowitz says. “The materials are produced in millions of tons per year for a range of applications.” It’s abundant, cheap, and after it’s filled with CO2, it takes relatively little energy to remove it. Unlike some other chemicals used for direct air capture, it doesn’t degrade, so it can also be used longer. The plants are cheap enough to build that they don’t have to run continuously to make economic sense. That means that it’s also possible to run on cheap, intermittent solar power from the grid. (The caveat: The company will be competing with data centers that also want to run on renewable energy and may be willing to pay more.) Sorbent cartridge being inserted into adsorption station [Photo: Clairity] While many companies in the space plan to inject CO2 into underground wells, that system isn’t ready yet in the U.S. Clairity is starting with another direction: adding the CO2 to materials. For example, if it’s combined with fly ash—a byproduct from coal power plants—it can be used to make lower-carbon concrete. It won’t be the first direct air capture company to use CO2 in concrete: A startup called Heirloom previously partnered with a cement company. But Clairity is unique in that it handles both steps itself. The CO2 can also be injected into other waste materials to permanently store it. Building an underground storage well costs millions of dollars, and the process of getting regulatory approval is slow; building the company’s “ex-situ” mineralization equipment costs less than $70,000. It’s at a much smaller scale, but it allows the company to begin storage now. “We can actually deliver credits today and not from some future project,” Meyerowitz says. There’s also the potential to make more money by selling value-added products rather than only selling credits for storage. The company expects to be one of two facilities in the world to deliver certified credits for carbon stored this year. The other, 4,000-plus miles away in Iceland, is Climeworks, which partners with a company called CarbFix to inject its captured CO2 into Iceland’s deep rock formations and naturally turn the CO2 into stone. Clairity chose Vegas as its first location for a few reasons. First, the particular sorbent it uses to capture the CO2 works best in an arid climate (some others, like Climeworks’s, are better in humid climates). Nevada has abundant access to renewable power. The state has relatively little arable land, so there are more potential locations; the company plans to expand in Nevada and other parts of the Southwest. And because the company’s process generates clean water on the side, there’s also a potential market to sell that water to local utilities. (The water is produced when the company heats up its sorbent to release the captured CO2; water comes out at the same time and is separately stored.) “You can imagine that in water-stressed Las Vegas, that’s a really interesting side benefit,” Meyerowitz says. For now, it’s operating on a tiny scale. Project Juniper can capture 100 metric tons of CO2 a year; society generated more than 40 billion tons of CO2 last year. Clairity’s cost right now is around $700 per ton of captured CO2—which will need to dramatically decline to be feasible over the long term. (Federal tax credits currently help with the cost, and may be more likely to stay in place than some other climate-related incentives because of strong Republican support.) Despite the challenges, Meyerowitz believes it’s possible for the startup to scale up to an ambitious goal: 10 megatons of C

In an industrial park in North Las Vegas, near an Amazon warehouse and a waste storage facility, a new carbon removal plant is beginning to pull CO2 from the air and store it permanently.

Called Project Juniper, it’s the first “integrated” plant of its kind in the U.S., meaning that it handles both carbon capture and storage in one place. (As a bonus, it also generates clean water.) Clairity Tech, the startup behind it, designed the new plant after raising a seed round of funding led by Initialized Capital and Lowercarbon Capital last year. After spending the last few months setting up the facility, it ran its full system for the first time last week.

Founder Glen Meyerowitz, who previously worked on rocket and spacecraft propulsion testing at SpaceX, pivoted to carbon removal in 2022. “As I look at it, this is really the existential threat of our time and the most important problem that needs to be addressed,” he says. In order for the world to have any chance of meeting climate goals, CO2 needs to be captured from the air at a massive scale at the same time as the economy decarbonizes. As Meyerowitz researched the space, he saw an opportunity to take a slightly different approach than some other companies.

First, Clairity uses a different material to capture CO2 from the air. “It’s in the same family as baking soda,” Meyerowitz says. “The materials are produced in millions of tons per year for a range of applications.” It’s abundant, cheap, and after it’s filled with CO2, it takes relatively little energy to remove it. Unlike some other chemicals used for direct air capture, it doesn’t degrade, so it can also be used longer.

The plants are cheap enough to build that they don’t have to run continuously to make economic sense. That means that it’s also possible to run on cheap, intermittent solar power from the grid. (The caveat: The company will be competing with data centers that also want to run on renewable energy and may be willing to pay more.)

While many companies in the space plan to inject CO2 into underground wells, that system isn’t ready yet in the U.S. Clairity is starting with another direction: adding the CO2 to materials. For example, if it’s combined with fly ash—a byproduct from coal power plants—it can be used to make lower-carbon concrete. It won’t be the first direct air capture company to use CO2 in concrete: A startup called Heirloom previously partnered with a cement company. But Clairity is unique in that it handles both steps itself. The CO2 can also be injected into other waste materials to permanently store it.

Building an underground storage well costs millions of dollars, and the process of getting regulatory approval is slow; building the company’s “ex-situ” mineralization equipment costs less than $70,000. It’s at a much smaller scale, but it allows the company to begin storage now. “We can actually deliver credits today and not from some future project,” Meyerowitz says. There’s also the potential to make more money by selling value-added products rather than only selling credits for storage.

The company expects to be one of two facilities in the world to deliver certified credits for carbon stored this year. The other, 4,000-plus miles away in Iceland, is Climeworks, which partners with a company called CarbFix to inject its captured CO2 into Iceland’s deep rock formations and naturally turn the CO2 into stone.

Clairity chose Vegas as its first location for a few reasons. First, the particular sorbent it uses to capture the CO2 works best in an arid climate (some others, like Climeworks’s, are better in humid climates). Nevada has abundant access to renewable power. The state has relatively little arable land, so there are more potential locations; the company plans to expand in Nevada and other parts of the Southwest. And because the company’s process generates clean water on the side, there’s also a potential market to sell that water to local utilities. (The water is produced when the company heats up its sorbent to release the captured CO2; water comes out at the same time and is separately stored.) “You can imagine that in water-stressed Las Vegas, that’s a really interesting side benefit,” Meyerowitz says.

For now, it’s operating on a tiny scale. Project Juniper can capture 100 metric tons of CO2 a year; society generated more than 40 billion tons of CO2 last year. Clairity’s cost right now is around $700 per ton of captured CO2—which will need to dramatically decline to be feasible over the long term. (Federal tax credits currently help with the cost, and may be more likely to stay in place than some other climate-related incentives because of strong Republican support.) Despite the challenges, Meyerowitz believes it’s possible for the startup to scale up to an ambitious goal: 10 megatons of CO2 removal in the next decade, or 100,000 times more than its first project.

![How 6 Leading Brands Use Content To Win Audiences [E-Book]](https://contentmarketinginstitute.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/content-marketing-examples-600x330.png?#)

![Building A Digital PR Strategy: 10 Essential Steps for Beginners [With Examples]](https://buzzsumo.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Building-A-Digital-PR-Strategy-10-Essential-Steps-for-Beginners-With-Examples-bblog-masthead.jpg)

![How Human Behavior Impacts Your Marketing Strategy [Video]](https://contentmarketinginstitute.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/human-behavior-impacts-marketing-strategy-cover-600x330.png?#)

![How to Use GA4 to Track Social Media Traffic: 6 Questions, Answers and Insights [VIDEO]](https://www.orbitmedia.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/ab-testing.png)