‘Is design dead?’ Design leaders wrestle with the question behind closed doors

Since the term “design thinking” took off in 2000, the once boutique industry of design became a household term. Spurred on by the stratospheric growth of Apple after the iPhone launch in 2007, businesses invested untold sums purchasing design companies and building design proficiency in-house. The cherry on top arrived when McKinsey published a report in 2018 cementing the value of design in leading businesses cross-sector. And then? For the last several years, the design industry has quietly lost some of its luster. We’ve published multiple stories examining how the world of business broke up with design, while a generation of design leadership has grappled with the effects. Truth be told, the reality is more complex. Design is still vastly more present within companies than it was decades ago, but it’s certainly been deprioritized during a business cycle that’s championing technology and marketing. Things look so bad because, for a moment, they looked so good. At Chicago’s The Future Of… conference in early March, dozens of design leaders—chief design officers, VPs, and other high ranking designers at companies including P&G, 3M, Ford, J.M. Smucker, Verizon, Duracell, Whirlpool, and GE Healthcare—gathered to respond to the provocation: “Is Design Dead?” My favorite moment was when design teams from Coca-Cola and PepsiCo formed an impromptu circle mere feet from a careful assortment of each company’s products on ice. Consultant John Gleason—who organized the conference alongside David Butler (Coca-Cola’s first VP of design) and industry vet Fred Richards—kicked things off by sharing some disquieting data. In analyzing hundreds for Fortune 500 companies, he found that 39% had cut the top one to two levels of their design organization, downgrading the level or title of heads of design. Nine percent had eliminated half of their design team in the last year. And in 84% of all cases, design reported not to the CEO, but to a specific function (like marketing) or functional executive. And in 74% of those cases? The head of design was not even reporting to the head of their functional unit. [Photo: Andrew Boynton] I was invited as the only journalist to attend the conference, to both share my perspective on stage and listen in to private, frank debates about the state of design and its future. Given the sensitivity of corporate perspectives being shared, I agreed to Chatham House Rule reporting. In other words, I could publish themes and even quote what was said, but for the protection of everyone, nothing will be attributed to anyone. [Photo: Andrew Boynton] Here were my 10 takeaways from two days of talks, though I would offer a significant caveat: Most designers in attendance worked for CPG companies, meaning this information is heavily biased toward that industry, versus what we might hear from technology, UX, product, interior design, etc. For the tl;dr version, let me say: Design is a practice as old as humankind. It can never and never will die. But for the industry to re-achieve its peak relevance, the practice needs to evolve, think bigger, and maybe go get that MBA already. 1. Yes, design is hurting at a lot of companies Companies have slashed back and demoted their design practices. With definite exceptions in the room, the general consensus was that designers were struggling to be relevant, and even have jobs, at their companies. “It’s a shitshow out there,” one person put it, bluntly, while another offered that “design is not healthy.” 2. Designers blew their big moment Out of 2010, the investment big in design teams promised true business innovation. When one panelist challenged the room to cite a major breakthrough design generated in this era, they were met with crickets. “We were sexy,” one person put it, but the farther you ride, the farther you fall.” The solution to earning back credibility in the meantime is that designers need to “do less with less,” another suggested, taking a more “surgical approach” to projects that could meet needs in the business. 3. We’re in a down cycle One of the most commonly recurring themes from the panels were about cycles of investment. That for whatever reason, we’re in a down cycle of design. I agree with this argument, and presented a take of my own: We are in a technological cycle and a marketing cycle. Gen AI drove the need for immediate investment in core technological capabilities. Mature social media (TikTok in particular) rewarded rich investment in data driven marketing campaigns. And in the meantime, design was deprioritized as a less essential job during years of cost cutting layoffs. However, designers will ultimately be the ones that turn AI into functional products, and there are only so many marketing collabs Gen Z will buy before they, too, prioritize more meaningful consumption, and sustainability (hopefully) becomes a global priority again. But for now, companies are abandoning climate pledges

Since the term “design thinking” took off in 2000, the once boutique industry of design became a household term. Spurred on by the stratospheric growth of Apple after the iPhone launch in 2007, businesses invested untold sums purchasing design companies and building design proficiency in-house. The cherry on top arrived when McKinsey published a report in 2018 cementing the value of design in leading businesses cross-sector.

And then? For the last several years, the design industry has quietly lost some of its luster. We’ve published multiple stories examining how the world of business broke up with design, while a generation of design leadership has grappled with the effects.

Truth be told, the reality is more complex. Design is still vastly more present within companies than it was decades ago, but it’s certainly been deprioritized during a business cycle that’s championing technology and marketing. Things look so bad because, for a moment, they looked so good.

At Chicago’s The Future Of… conference in early March, dozens of design leaders—chief design officers, VPs, and other high ranking designers at companies including P&G, 3M, Ford, J.M. Smucker, Verizon, Duracell, Whirlpool, and GE Healthcare—gathered to respond to the provocation: “Is Design Dead?” My favorite moment was when design teams from Coca-Cola and PepsiCo formed an impromptu circle mere feet from a careful assortment of each company’s products on ice.

Consultant John Gleason—who organized the conference alongside David Butler (Coca-Cola’s first VP of design) and industry vet Fred Richards—kicked things off by sharing some disquieting data. In analyzing hundreds for Fortune 500 companies, he found that 39% had cut the top one to two levels of their design organization, downgrading the level or title of heads of design. Nine percent had eliminated half of their design team in the last year. And in 84% of all cases, design reported not to the CEO, but to a specific function (like marketing) or functional executive. And in 74% of those cases? The head of design was not even reporting to the head of their functional unit.

I was invited as the only journalist to attend the conference, to both share my perspective on stage and listen in to private, frank debates about the state of design and its future.

Given the sensitivity of corporate perspectives being shared, I agreed to Chatham House Rule reporting. In other words, I could publish themes and even quote what was said, but for the protection of everyone, nothing will be attributed to anyone.

Here were my 10 takeaways from two days of talks, though I would offer a significant caveat: Most designers in attendance worked for CPG companies, meaning this information is heavily biased toward that industry, versus what we might hear from technology, UX, product, interior design, etc.

For the tl;dr version, let me say: Design is a practice as old as humankind. It can never and never will die. But for the industry to re-achieve its peak relevance, the practice needs to evolve, think bigger, and maybe go get that MBA already.

1. Yes, design is hurting at a lot of companies

Companies have slashed back and demoted their design practices. With definite exceptions in the room, the general consensus was that designers were struggling to be relevant, and even have jobs, at their companies. “It’s a shitshow out there,” one person put it, bluntly, while another offered that “design is not healthy.”

2. Designers blew their big moment

Out of 2010, the investment big in design teams promised true business innovation. When one panelist challenged the room to cite a major breakthrough design generated in this era, they were met with crickets. “We were sexy,” one person put it, but the farther you ride, the farther you fall.” The solution to earning back credibility in the meantime is that designers need to “do less with less,” another suggested, taking a more “surgical approach” to projects that could meet needs in the business.

3. We’re in a down cycle

One of the most commonly recurring themes from the panels were about cycles of investment. That for whatever reason, we’re in a down cycle of design. I agree with this argument, and presented a take of my own: We are in a technological cycle and a marketing cycle. Gen AI drove the need for immediate investment in core technological capabilities. Mature social media (TikTok in particular) rewarded rich investment in data driven marketing campaigns. And in the meantime, design was deprioritized as a less essential job during years of cost cutting layoffs. However, designers will ultimately be the ones that turn AI into functional products, and there are only so many marketing collabs Gen Z will buy before they, too, prioritize more meaningful consumption, and sustainability (hopefully) becomes a global priority again. But for now, companies are abandoning climate pledges to build AI data centers.

4. Designers sell their practice without solidifying their value

One theme I noticed was that designers in the room that still boasted rich investment from their companies proselytized the quantifiable impact of their work—often that they saved their company money, or measurably added brand equity—whereas most admitted that designers were poor at articulating the ROI of their own practice.

But you know who is great at talking ROI? CMOs. “Marketing leaders can outline their strategy. Design leaders can’t,” someone said. “No wonder design has trouble competing with marketing on solutions.” These days, many design teams are answering to a CMO, which is a failure of designers’ self-marketing inside the company. As one design leader pointed out, they see three paths forward: One, marketing takes over design. Two, marketing and design share responsibilities. Or the third, where marketing reports to design. To most designers, the third option is the most ideal—but it also might be the most sustainable for business. Design as a broad practice can contain marketing, while marketing does not naturally contain the umbrella of design.

5. Designers have failed to speak the language of business

Why don’t designers keep the ear of the C-suite? “Enough designers don’t speak the language of business,” one person put it, flatly. And over two days, several people pointed out that designers simply do not know the proper lingo to be taken seriously inside companies. Designers tend to be spreadsheet adverse as they hang their hats on liberal arts. Especially at large organizations, most business units will be run by MBAs and traditional, business-minded people. This mismatch creates friction to sway a CEO, sure, but the issue compounds as designers really need buy-in from cross functional teams to make things happen. “Our gift is synthesis, which is why we need to bring in our own data,” said one leader. “I spend all my time building relationships [across the company] to get to that data.”

6. Design thinking has undercut the value of design

Over two days of talks, I witnessed all variety of reaction to the term “design thinking.” But especially with the fall of Ideo—the mecca of design thinking—it’s clear that the term has often become shorthand for, what an IDEO partner once framed to me as enabling a “theater of innovation.”

It’s a methodology to problem solving akin to the scientific method, and it’s every bit as intelligent as the person wielding it. Yet the design industry has spent two decades rallying behind the term, leveraging it to get buy-in from companies that used it to teach everyone “how to think like a designer.” But “Design thinking is not design, and there’s a huge disservice done when educating business on how to run a design thinking session,” said one panelist. Namely, it cheapens the practice of design, commoditizing a craft to something you learn over a box lunch. “If the height of the [design] curve was the Ideo shopping cart video, we may be in the pit of despair right now,” joked another. Not everyone at a company is a designer. Just like they aren’t all an accountant. Or an IT specialist.

7. Maybe design needs a new name

There is no vagary what someone means when they tell you they are an “architect.” But what does a “designer” conjure? A million possible things. “The term ‘design’ is a problem,” says one expert, noting that we’ve tried being more specific with “CX” and “UX” but each permutation comes with its own costs. “The term ‘interior design’ is more limiting than effective,” they posit. The terms seem either too big, or too small, for designers to fit any definitional impact.

8. Design’s lack of diversity limits its reach

We’ve reported on the lack of diversity within design for the last decade and, over that time, the numbers haven’t measurably improved. Noting the majority of whiteness in the room, one designer said, “We design for people who don’t look like most designers.” I’ll admit some disappointment by how shocked some in the room were at this statement. (Should we really be surprised to contemplate that design is too white in 2025?) But that doesn’t make it any less true. With the current administration’s attacks on DEI, diversifying design is only a greater uphill battle. However, design representation isn’t just a path toward equality; it’s a path toward understanding the needs and desires of more customers.

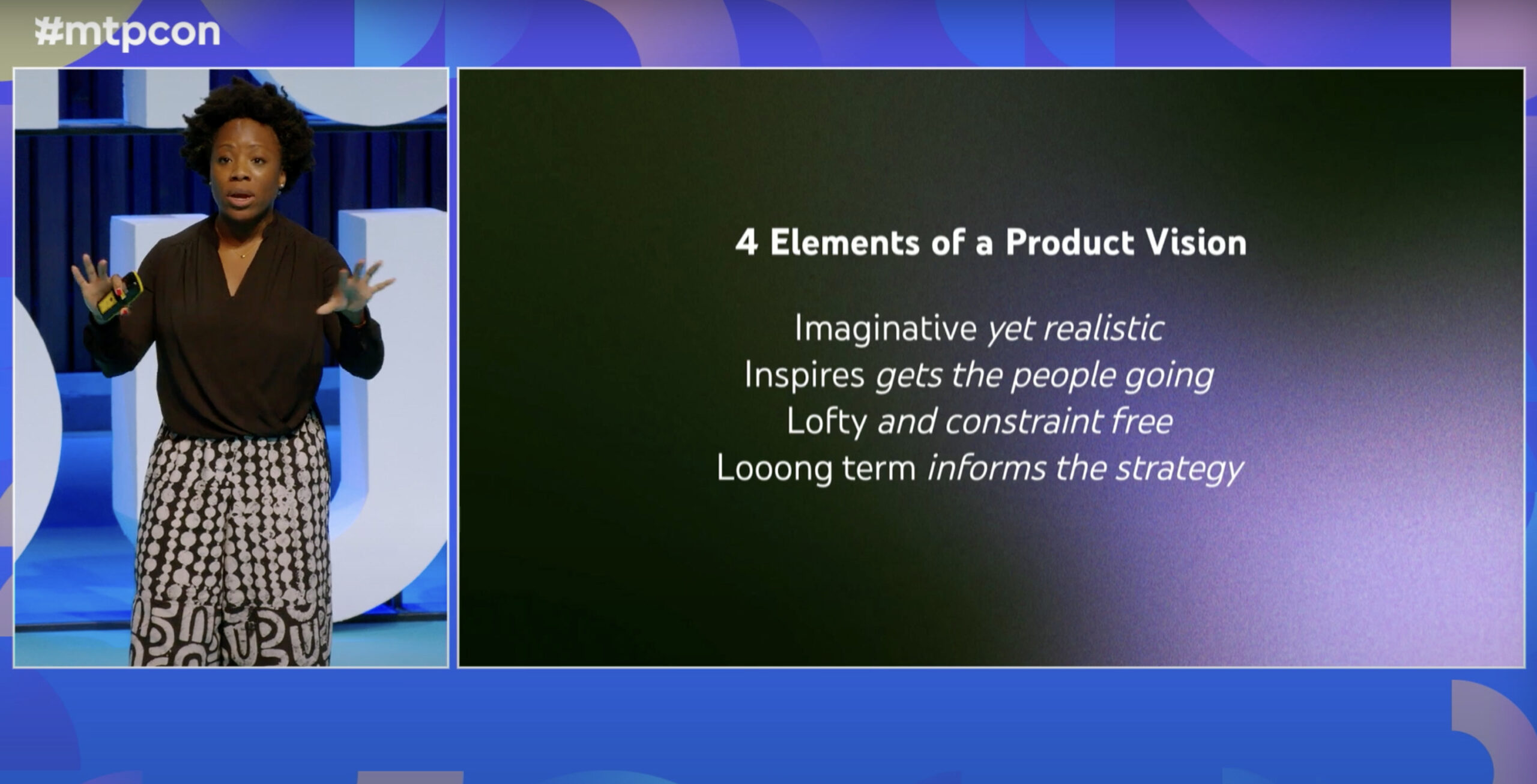

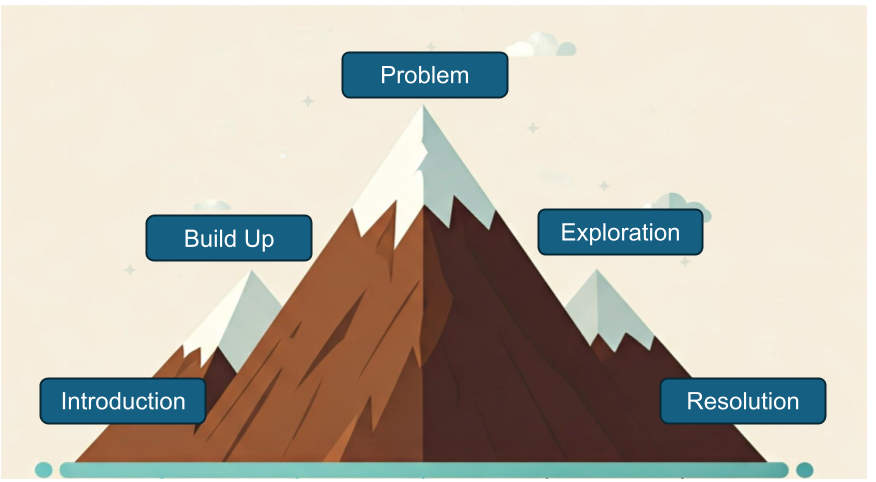

9. Corporate reorgs kill design strategy

Whether it’s a new CEO or a completely new org chart, the increased instability of business drives an instability of the design practice. “I’ve had seven reorgs in four years,” one designer lamented—who was not the only one to share such a sentiment during the week. But why is this bad for design? As many echoed through the conference, designers think well in the medium- to long-term, strategizing for the future. When that lead time is disrupted through a change in leadership or a reorg—or even just the quarterly whims of Wall Street—any true long-term design strategy cannot take off. As a point of example, CEO Bracken Darrell was cited as turning around Logitech in four years alongside designer Alastair Curtis. And now, as the two have landed VF Corporation, they’ve charted a decade-long strategy.

10. Design is still better off than it was 25 years ago

While design may be in something of a corporate slump, I continue to believe in its unequivocal value. And I do think it’s worth taking a little rewind through history. Design was not something most people knew about 25 years ago–especially in the U.S. The corporate world only got its first chief design officer in 2010, when Mauro Porcini (now of PepsiCo) took the position at 3M. “We don’t know the half life of a CDO yet,” one leader pointed out. “A CEO is about four years, a CMO is about two years.” The truth is that, while design is an impossibly old practice across culture, its serious role within business is still nascent.

![How 6 Leading Brands Use Content To Win Audiences [E-Book]](https://contentmarketinginstitute.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/content-marketing-examples-600x330.png?#)

![Building A Digital PR Strategy: 10 Essential Steps for Beginners [With Examples]](https://buzzsumo.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Building-A-Digital-PR-Strategy-10-Essential-Steps-for-Beginners-With-Examples-bblog-masthead.jpg)

![How Human Behavior Impacts Your Marketing Strategy [Video]](https://contentmarketinginstitute.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/human-behavior-impacts-marketing-strategy-cover-600x330.png?#)

![How to Use GA4 to Track Social Media Traffic: 6 Questions, Answers and Insights [VIDEO]](https://www.orbitmedia.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/ab-testing.png)