Lesson 2: The three questions for effective meta-learning

In anticipation of a new session of my popular course, Rapid Learner, I’m sharing a four-part lesson series on how to create successful learning projects. In the first lesson, I distinguished the key differences between project finishers and project starters. Today, I’d like to discuss how to make the projects you undertake effective. How can […] The post Lesson 2: The three questions for effective meta-learning appeared first on Scott H Young.

In anticipation of a new session of my popular course, Rapid Learner, I’m sharing a four-part lesson series on how to create successful learning projects. In the first lesson, I distinguished the key differences between project finishers and project starters.

Today, I’d like to discuss how to make the projects you undertake effective. How can you ensure that the projects you work on actually help you get better at the things you’re trying to get better at?

To succeed in our efforts at improvement, we need two types of knowledge:

- Knowledge of the domain. In Spanish, this includes the words “agua” and the difference between “estar” and “ser.” In programming, the difference between a variable and a constant. In calculus, how to take a derivative.

- Knowledge of how the domain is organized. Learning Spanish requires learning vocabulary, grammar and pronunciation. Learning programming requires remembering syntax and having a mental model of what each line of code is doing. Learning calculus requires memorizing transformation rules, as well as developing a spatial intuition about rates of change.

Meta-learning is the second kind of knowledge. It is your “map” of a domain that you use to plan what you intend to learn. And, just as in real navigation, when you have a good map, you’re less likely to wander aimlessly on your way to your destination.

To create this map successfully, there are three major questions to keep in mind:

Question #1: How do other people draw the map?

Learning anything on your own has a bootstrapping problem. Learning and meta-learning are intertwined, so the less we know about a subject, the less we know about how that subject is organized. This leads to our first principle: before embarking on any new learning project, try to figure out how other people organize efforts to learn it. What do those people see as the major divisions in skill, knowledge and practice?

Is the skill taught in school? If so, how do people organize curricula around it? Is it taught in books, courses or apprenticeship programs? How do those typically proceed?

Fortunately, research here has gotten much easier. Google and, more recently, LLM tools like ChatGPT can offer starting points for understanding novel topics. You can now get a glance at how experts break down a topic with just a few clicks.

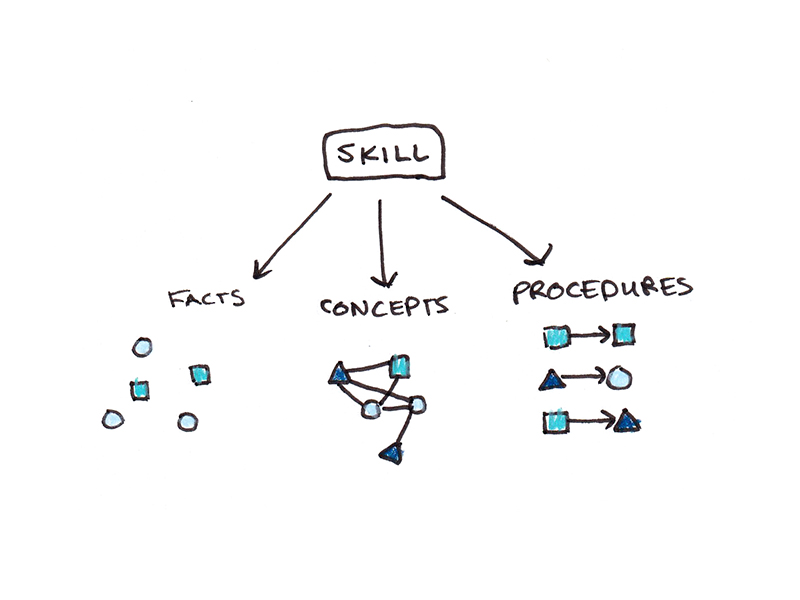

Question #2: What facts, concepts and procedures must be acquired?

Once you have a rough map, it’s time to fill in the details. All learning is composed of a few basic “atoms” of knowledge in three main types:

- Facts—things which need to be memorized. Words, terms, formulas, dates, jargon.

- Concepts—things which need to be understood. Principles, ideas, narratives, explanations.

- Procedures—things which need to be performed. Methods, steps, actions, techniques.

This applies across fields. Learning Spanish breaks down into facts (vocabulary), concepts (such as the difference between estar/ser), and procedures (like grammar and pronunciation). Learning programming breaks into facts (like syntax), concepts (design patterns), and procedures (like how to write a for-loop). Learning calculus has facts (e.g., cosine is the derivative of sine), concepts (such as what a limit is), and procedures (like the chain rule).

This framework transforms an otherwise amorphous process of improvement into, essentially, a to-do list. To learn a skill you simply need to perform the techniques that are useful for learning each type of knowledge, such as memorization for facts, explanation for concepts, and practice for procedures.

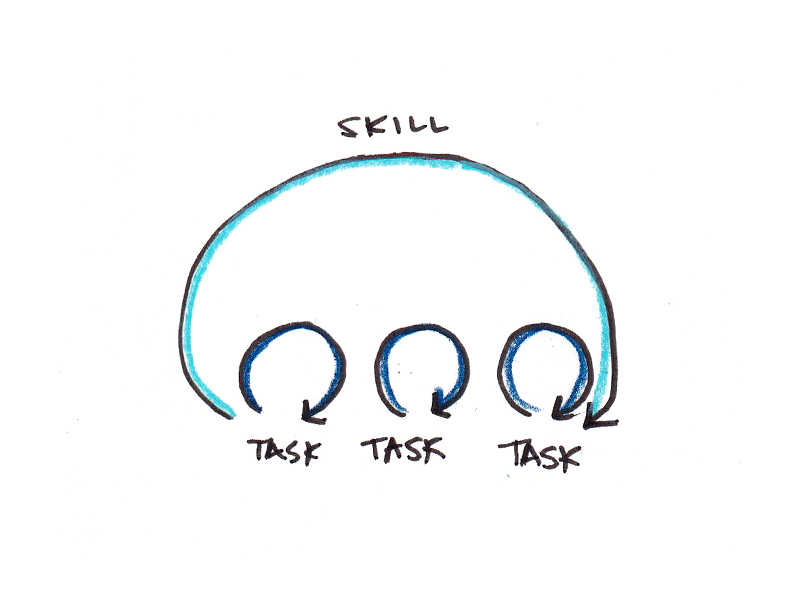

Question #3: What fine-tuning and feedback are needed?

Drawing the map and identifying the “atoms” of the skill you want to learn is powerful, but it is rarely sufficient. Maps never fully reflect the territory—what looks like a straight road may unexpectedly be a dead-end. What appears to be a simple concept or procedure may disguise enormous tacit knowledge and intuition.

Simply checking off items on the to-do list can backfire if the way you are learning those “atoms” doesn’t match with how they need to combine in real skills and situations. As such, the process of successful learning requires constantly rewriting the map and reshuffling the to-do list. You learn a bit, see what’s working and what isn’t, and adjust your approach accordingly.

This means good learning projects require two activities in parallel:

- Drills to work through the “atoms” of learning you’ve identified. This means reading books, memorizing terms, practicing procedures and understanding the essential concepts.

- Direct practice both to test how closely your learning efforts match reality, and to integrate and combine the “atoms” in ways that are useful. This includes solving problems, writing code, or using the language to communicate. Direct practice means applying the skill you are learning to real life.

Bringing it all together

The end result is a learning project that is both practical and flexible.

Practical, because it is grounded in expert understanding of how the skill or subject is organized, and because it has been broken down from vague notions of “improvement” into specific facts, concepts and procedures.

Flexible, because by combining drills to master the atoms with doing direct practice to test out your map, you ensure you can make any needed changes to your project so those atoms combine successfully into real skills.

There is, of course, more to this process than I can explain in one lesson. This was a major motivation behind developing my full, six-week course Rapid Learner. Teaching the art and science of meta-learning, this course will guide you through how to design projects to master any skill or subject you care about. I’ll send out registration information on Monday. In the next lesson, I’d like to turn from meta-learning to productivity. After all, a plan is only paper. Effective learning means execution—how can you go from someone with great plans, to someone who consistently gets the work done?

The post Lesson 2: The three questions for effective meta-learning appeared first on Scott H Young.