Today’s Essential Power Skill for Leaders: Cooperation

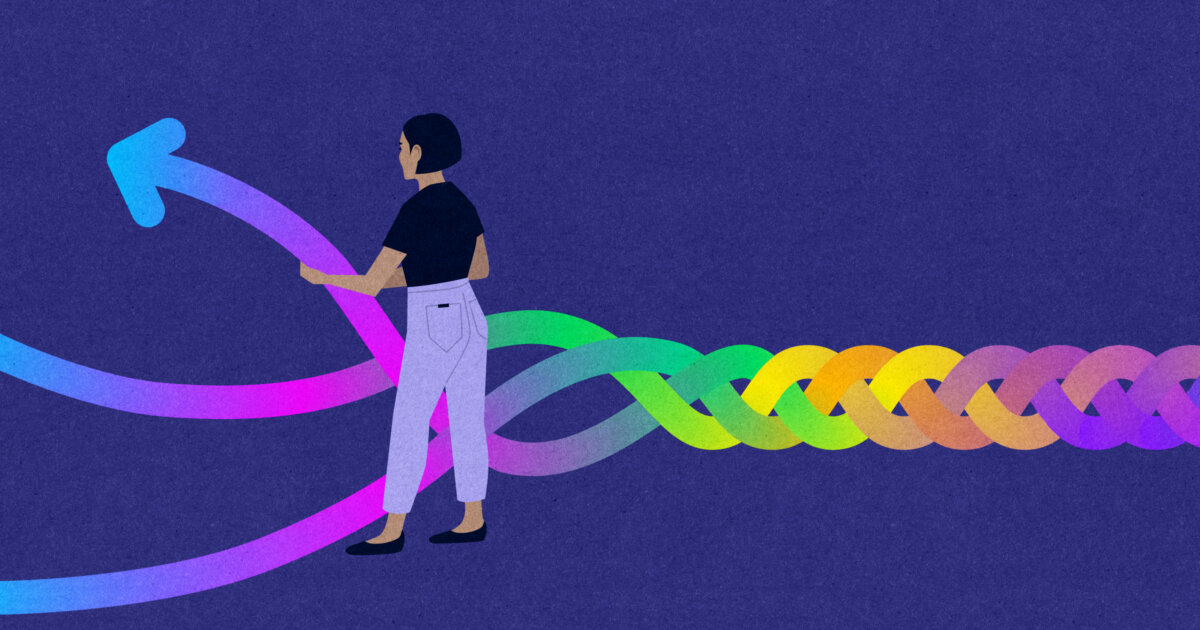

Carolyn Geason-Beissel/MIT SMR | Getty Images “I want to work in a way that is both productive and brings me joy — what does that look like, and how might I achieve this?” I’ve studied working lives for over 20 years, talking to thousands of executives, the MBA students I teach, and leaders of the […]

Carolyn Geason-Beissel/MIT SMR | Getty Images

“I want to work in a way that is both productive and brings me joy — what does that look like, and how might I achieve this?”

I’ve studied working lives for over 20 years, talking to thousands of executives, the MBA students I teach, and leaders of the companies I advise. I’ve also directed a series of research initiatives taking a closer look at how we work. What I hear — either explicitly or in an undercurrent of tiny indecisions and hesitancies — is that people are searching for work lives that are both productive and joyful.

In reflecting on productivity and joy over the past three years, I’ve thought deeply about my own working life. I’ve surfaced memories from the earliest points of my career and considered the challenges I’ve faced. I’ve also taken a deeper look at emerging research and spoken to experts. In the process, I’ve learned more about myself and about the world.

I’m now more sure than ever that great working lives are built through the skills we master and how we work with others. These two elements make us productive and give our work meaning. I think of those two elements — mastery and cooperation — as threads that hold the fabric of a long working life together. Keeping these threads strong means purposely investing our time, resources, and connections. Now more than ever, technology is transforming work, and external events, like the pandemic and economic downturn, are changing its dynamics. So we must be ever more adaptive and flexible in the ways we prioritize mastery and cooperation.

When you master an area of competence — such as managing projects, leading multinational teams, preparing strategy documents, negotiating complex deals, or coaching others — you are creating a foundation for productivity. If you choose an area of mastery that brings you satisfaction, you have a chance at finding joy and meaning. In a previous column, I reflected on how we develop mastery in ourselves and what leaders do that helps or impedes that growth in others. Here, I want to focus on the other critical aspect of productivity: cooperation.

The Entwined Threads of Mastery and Cooperation

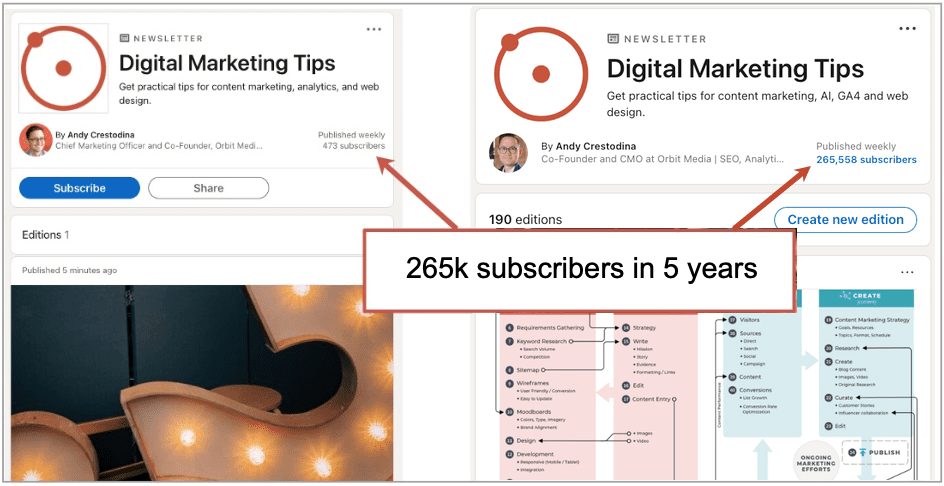

In 2010, Boris Groysberg, a professor at Harvard Business School, published Chasing Stars: The Myth of Talent and the Portability of Performance, about his seminal study on the performance of investment analysts. The narrative of the job of the investment analyst is that success is all about individual endeavor — analytical skills, the capacity to understand vast swaths of information, the ability to bring this information together in a coherent form to make buying recommendations. In other words, it’s all about individual mastery. So it’s no surprise that when investment firms headhunt for these skills, it’s the individual star performer they’re after.

The question Groysberg asked was this: When an analyst leaves to join a new firm, does their performance increase, remain the same, or decrease? If, indeed, performance is solely about individual effort, the expectation would be that the performance of a top player would remain the same. (Groysberg explored the analyst role because it’s one of the few job categories where it’s possible to collect reliable performance data over time and across firms.)

But Groysberg’s analysis showed that, in most cases, an analyst’s star performance lost its luster after a move. Eventually, the old productivity and mastery returned, but it took time.

The finding reflected a simple truth: that part of analysts’ work involves collaborating with a wider network of people. When they leave a company, they leave behind their professional community, networks, and friendships. In doing so, their performance suffers. While the job, on the face of it, is an individual-centered occupation where mastery is crucial, it’s also a role with a whole range of cooperative characteristics that need to be performed successfully.

Groysberg’s finding rings true for most of us, in myriad careers. These networks help us build the mastery necessary to be productive.

Consider your own networks. At the center is you, and arrayed around you are those strong network ties with the people you’re closest to. Some are similar to you — such as work colleagues you know well and spend time with. If they are more expert than you are, there is much you can learn from them. Because they know what “good” looks like, they are in a position to provide tough feedback. When I reflect on the memories of my own path to mastery, this type of hard feedback from people on the same path of mastery was incredibly important to my development.

You probably have some strong connections with people who are dissimilar to you — perhaps from another part of the company, or from another part of your working life. Some of them may have networks that reach into places yours do not or skills that you lack. If they can help you learn these distinct talents, your own abilities might morph into an adjacent area of mastery. I recall how, years ago, a close colleague showed me how to think about change management, an area in which I had no skills. Later in my working life, when building a consulting research practice, those change skills became crucial.

And then there are weak ties at the outer periphery of your networks. Their sheer number and variety make them rich with potential. Within this diverse crowd could be role models that inspire you to take another pathway — images of the future you. I can recall a number of times in my own life when I have seen someone from afar and been profoundly touched by characteristics or skills they have that I would love to make part of my future self.

The Fragility of Cooperation — and How to Strengthen It

Many of the experiences from which mastery is created are solitary — you are head down, focused, wrestling a problem to the ground. These self-sufficient times are crucial to productivity. Many of our jobs require periods for focus and concentration to feel the flow of energy and inspiration.

But most of us don’t work on our own all the time. We work sometimes in partnership, occasionally in teams, perhaps as members of much larger communities. These can be some of the most innovative and fun moments of our working lives. That’s why the ability to be good at cooperation is so powerful in creating resilience and productivity.

In my research on how and why we cooperate (which I wrote about in my books Hot Spots and Glow), I discovered many positive benefits:

- Cooperating helps you solve tough problems. When teams work to solve a complex challenge, the likelihood is that they will come to a better solution than if the members worked on their own.

- Cooperating helps you feel good. Working with others can be exciting. It offers moments that can be playful and creative.

- Cooperating boosts your productivity. When you work with others, you have a chance to improve your own performance as others introduce you to ideas, share tips, and give feedback.

Cooperating isn’t always easy, though. The connections that make cooperation possible can be fragile. I’ve discovered that this fragility often takes two forms. The first is indifference/busyness: There is nothing that really holds the cooperative partnership together, and you each go your own way. The second is unproductive conflict: The relationship deteriorates as you lose trust in each other and your differences overwhelm your shared interests.

In my experience, these two tricky challenges to cooperation can be tackled with focus and intent.

Overcome indifference and busyness with an igniting question.

One of my fondest memories of cooperation is working with Andrew Scott on our book The 100-Year Life. Andrew and I are both professors at London Business School, but we did not know each other until we spoke at a conference in Shanghai about the new demographic realities of aging populations. On the plane journey back, we had a great conversation about our research and interests. But at the end of the trip, we went our separate ways — returning to our respective departments and our separate teaching and research commitments. We had demanding schedules and were under the regular pressures of the day-to-day. How often have you met with someone and been excited about the encounter, only to lose the momentum as you step back into your busy life?

Yet that little flame, created by our joint curiosity about aging and work, kept burning. If either of us saw a newspaper article, talked to someone about shifting demographics, or encountered a research study on the topic, we flicked it over to the other, often with a simple question: “What do you think?” This connection bubbled away on the back burner.

It was two years later before we both found ourselves with sufficient time and headspace to think about really trying to collaborate. To get over the barrier of busyness, Andrew and I committed to setting aside time every week — usually two hours — to pursue that flame of a question: “What happens when everyone lives to 100?” This was an opportunity for an open conversation, ranging across many topics. These conversations went on for over two years, leading to our 2016 book, a 2017 article, “The Corporate Implications of Longer Lives,” for MIT Sloan Management Review, and an ongoing dialogue.

I’m still struck by the power of conversation and the importance of making time for cooperating with others. This is a good area for you to reflect on: What issues and challenges are currently on your back burner that you could bring forward? That question could ignite a valuable new direction of collaboration for you and be powerful enough to overcome busyness.

Overcome unproductive conflict with a cooperative mindset.

As I look closely at my own cooperative encounters and consider the research on cooperation, I realize that being cooperative is a state of mind. It’s about putting sharing above hoarding, being generous rather than holding back, and putting the collective interest above your individual interest. Not everyone is cooperative all the time, and I am sure you know people who never acknowledge others, are rarely prepared to share, and think getting ahead means competing head-on. You’ve probably been in work environments that are highly competitive, with much backstabbing. None of this is conducive to building those strong and weak network ties that will be crucial as you develop mastery and productivity.

Still, being prepared to cooperate with others starts with you. It’s a state of mind, but it also reflects the company you keep. If your group is cooperative, with cooperative norms, you’re more likely to follow the norm. Cooperation is contagious.

This is the next area to reflect on: In every work situation, there will be times to cooperate or compete, but what’s the overall tenor? Do senior executives cooperate or do they compete? Is cooperating rewarded? Do highly competitive people get paid more than others? Ask yourself these observational questions to be clear about your sense of the place and its culture and norms.

My advice if you’re in an organization where cooperation does not flourish: Either stay and acknowledge that these are the games and that over time you will inevitably become more competitive and less cooperative, or leave and find a job where there are stronger cooperative norms of behavior — where you can learn and get all the upsides that come with collaborative work.

Being cooperative will inevitably become a strong and important thread in your long working life. Sure, there will be times when cooperation fails you — when you’re cooperating with someone who’s too competitive and taking more than they give, or when you feel that the question you’re asking is simply not sufficiently exciting to keep the spark of partnership going.

But building wide and diverse networks will be crucial to how you develop in the coming years and decades. When you’re cooperative and open to others, you’re more likely to build these important and wide-ranging networks. In these networks could be the ideas you haven’t considered, the perspectives that could open new doors, the people who might be future role models — the vision of who you could become.

Acknowledge that our being cooperative is a fragile state that is easily overwhelmed by indifference and busyness and easily hijacked by unproductive conflict. Finding an igniting question that overcomes indifference and developing a cooperative mindset that challenges unproductive conflict will be key.