Why this EV charging company just helped electrify an entire village in Senegal

In a small village in Senegal, almost no one has electricity, but that’s about to change. Last year, a 40-foot-shipping container rolled into town, unfolded an array of solar panels on its roof, and crews began running wires to connect the whole village to clean power. After final approvals from the local government, the new microgrid will soon switch on. The project had an unusual funding source: ChargePoint, the EV charging company known for its network of a million chargers in the U.S. and Europe, spent six figures helping get it built, working with a technology partner called Africa GreenTec. The EV charging company used money that it earned selling carbon credits from 10,000 EV chargers in Germany. Under the EU’s emissions trading program, it gets certificates for replacing gas or diesel fuel in cars with electricity. But since the electricity used to charge cars isn’t yet 100% clean, the company wanted to use the carbon credit funds to go a step farther. (Germany’s grid reached a record of 62.7% renewable energy in 2024, but still uses some coal and natural gas.) “From the very beginning, we said we are going to set aside a certain amount of money for each kilowatt hour,” says Andreas Blin, director of segments and partnerships at ChargePoint. “And this is going to be invested into a renewable energy product or project, just to make sure that everybody’s clear that we are not about greenwashing—we’re about burning less fossil fuels.” [Photo: courtesy ChargePoint] As the team considered where to spend the funds, it decided to partner with Africa GreenTec, a company that makes a mobile system called the Solartainer Amali, designed to quickly deploy solar power and electrify entire communities. The first project was built in Keur Ndiangane, a village with around 1,200 residents on the southern border of Senegal. Most people living there are subsistence farmers, dealing with a harsh climate that swings between floods and droughts. “Before our project, Keur Ndiangane had no access to centralized electricity or public lighting,” says Wolfgang Rams, CEO of Africa GreenTec. “Daily life effectively ended at sunset—shops closed, schools emptied, and the streets were plunged into darkness. Most households relied on candles or kerosene lamps.” Some small businesses, such as mills that process grains, ran on expensive diesel generators. To install the new microgrid, a crew spent a few weeks getting the “Solartainer”— which has 144 solar panels and battery storage—ready to run. (The process is normally even faster, but installation was slower because of extreme heat). At the same time, they spent two months putting up more than 100 poles and nearly 16,000 feet of wiring for the new grid. They also added 55 street lights that each run independently off their own solar panels, helping improve safety for people walking at night. [Photo: courtesy ChargePoint] Families can sign up for different plans depending on what time of day they want to use electricity and how much they need. More than 140 people are pre-subscribed so far. (ChargePoint doesn’t own any part of the project and won’t get any financial return from it.) The impact will be significant. In the past, while families might have used candles or kerosene for light at night, they’ll now easily be able to use bright LED lights and charge other small appliances. “Children can study in the evening,” Blin says. “People can work in the evening . . . This extends the daytime that people can use.” It can help enable internet access and refrigeration. Farmers can use the power to pump water on their fields, or run equipment to make new products, such as peanut oil. Healthcare clinics can use lighting and refrigerate medicine. New jobs have been created, as local residents will maintain the new solar microgrid. In other areas where Africa GreenTec has installed solar microgrids in the past, it has seen that electrification trigger economic growth—and then there’s more demand for power. Because of that, the system has been designed to adapt. The village can swap in a larger, more powerful solar microgrid when it’s needed, and the original Solartainer can be packed up and reused. “The previously used Solartainer Amali can be transported to the next village that is not yet electrified and can be used there again at any time,” says Rams. “This unique feature saves production effort and resources and reduces our carbon footprint.” The work is part of a much larger trend: Solar microgrids are quickly spreading across Africa. In Zambia, as one example, the government has installed 45 microgrids in rural communities, with plans for another 200 by next year, and 1,000 over the next few years, with support from nonprofits, the UN, and other funders. In Nigeria, World Bank funding has helped millions of people access electricity from solar microgrids in recent years. Last year, World Bank lending for off-grid solar projects reache

In a small village in Senegal, almost no one has electricity, but that’s about to change. Last year, a 40-foot-shipping container rolled into town, unfolded an array of solar panels on its roof, and crews began running wires to connect the whole village to clean power. After final approvals from the local government, the new microgrid will soon switch on.

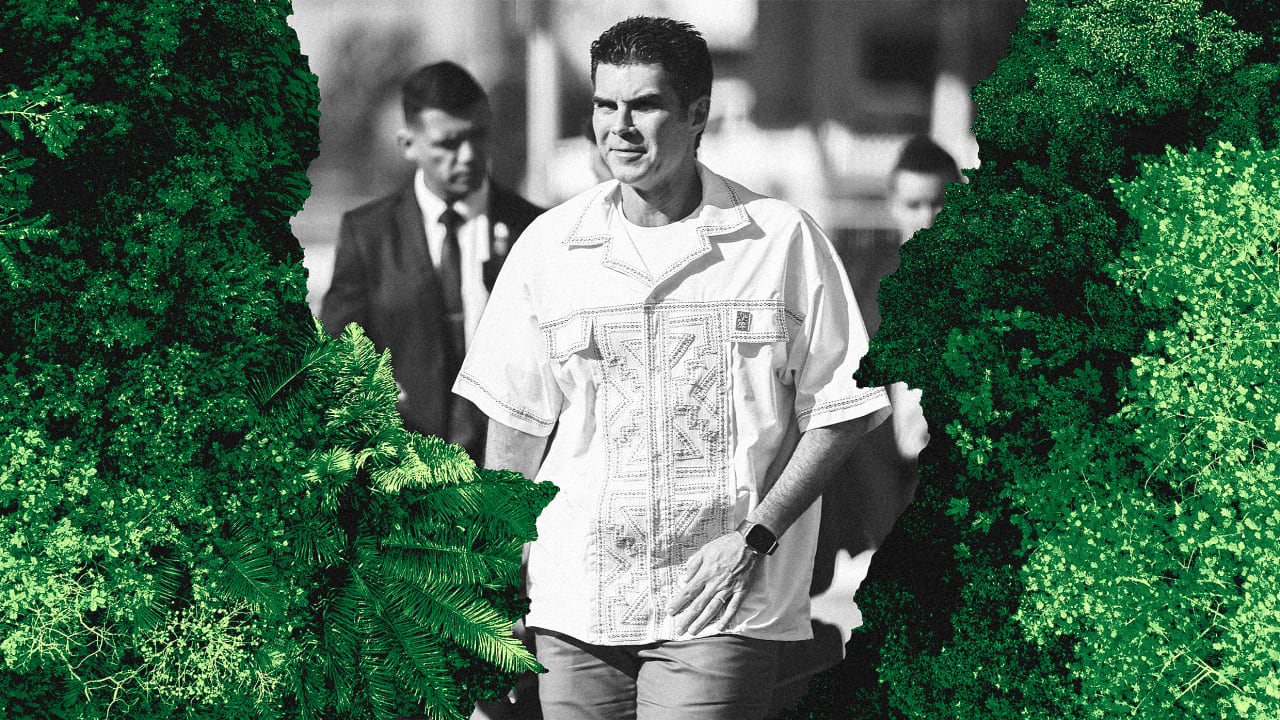

The project had an unusual funding source: ChargePoint, the EV charging company known for its network of a million chargers in the U.S. and Europe, spent six figures helping get it built, working with a technology partner called Africa GreenTec.

The EV charging company used money that it earned selling carbon credits from 10,000 EV chargers in Germany. Under the EU’s emissions trading program, it gets certificates for replacing gas or diesel fuel in cars with electricity. But since the electricity used to charge cars isn’t yet 100% clean, the company wanted to use the carbon credit funds to go a step farther. (Germany’s grid reached a record of 62.7% renewable energy in 2024, but still uses some coal and natural gas.)

“From the very beginning, we said we are going to set aside a certain amount of money for each kilowatt hour,” says Andreas Blin, director of segments and partnerships at ChargePoint. “And this is going to be invested into a renewable energy product or project, just to make sure that everybody’s clear that we are not about greenwashing—we’re about burning less fossil fuels.”

As the team considered where to spend the funds, it decided to partner with Africa GreenTec, a company that makes a mobile system called the Solartainer Amali, designed to quickly deploy solar power and electrify entire communities.

The first project was built in Keur Ndiangane, a village with around 1,200 residents on the southern border of Senegal. Most people living there are subsistence farmers, dealing with a harsh climate that swings between floods and droughts.

“Before our project, Keur Ndiangane had no access to centralized electricity or public lighting,” says Wolfgang Rams, CEO of Africa GreenTec. “Daily life effectively ended at sunset—shops closed, schools emptied, and the streets were plunged into darkness. Most households relied on candles or kerosene lamps.” Some small businesses, such as mills that process grains, ran on expensive diesel generators.

To install the new microgrid, a crew spent a few weeks getting the “Solartainer”— which has 144 solar panels and battery storage—ready to run. (The process is normally even faster, but installation was slower because of extreme heat). At the same time, they spent two months putting up more than 100 poles and nearly 16,000 feet of wiring for the new grid. They also added 55 street lights that each run independently off their own solar panels, helping improve safety for people walking at night.

Families can sign up for different plans depending on what time of day they want to use electricity and how much they need. More than 140 people are pre-subscribed so far. (ChargePoint doesn’t own any part of the project and won’t get any financial return from it.)

The impact will be significant. In the past, while families might have used candles or kerosene for light at night, they’ll now easily be able to use bright LED lights and charge other small appliances. “Children can study in the evening,” Blin says. “People can work in the evening . . . This extends the daytime that people can use.”

It can help enable internet access and refrigeration. Farmers can use the power to pump water on their fields, or run equipment to make new products, such as peanut oil. Healthcare clinics can use lighting and refrigerate medicine. New jobs have been created, as local residents will maintain the new solar microgrid.

In other areas where Africa GreenTec has installed solar microgrids in the past, it has seen that electrification trigger economic growth—and then there’s more demand for power. Because of that, the system has been designed to adapt. The village can swap in a larger, more powerful solar microgrid when it’s needed, and the original Solartainer can be packed up and reused.

“The previously used Solartainer Amali can be transported to the next village that is not yet electrified and can be used there again at any time,” says Rams. “This unique feature saves production effort and resources and reduces our carbon footprint.”

The work is part of a much larger trend: Solar microgrids are quickly spreading across Africa. In Zambia, as one example, the government has installed 45 microgrids in rural communities, with plans for another 200 by next year, and 1,000 over the next few years, with support from nonprofits, the UN, and other funders.

In Nigeria, World Bank funding has helped millions of people access electricity from solar microgrids in recent years. Last year, World Bank lending for off-grid solar projects reached $660 million. The World Bank Group has also partnered with the African Development Bank with a goal of connecting 300 million people in sub-Saharan Africa to electricity by 2030.

Those larger efforts dwarf what a single company can do. Still, Africa GreenTec says that ChargePoint’s support meant that the village of Keur Ndiangane likely got power faster than it otherwise would have. “Without ChargePoint’s financing, implementing the project would have been extremely difficult,” Rams says.

ChargePoint, founded in California in 2007, has been navigating a difficult period, with net losses of $282.9 million in the fiscal year ending in January, and around 250 jobs cut in 2024. It’s also earning less money now from carbon credits, because the value of carbon credits has fallen. Still, its network of EV chargers continues to grow, and the company expects to invest in electrifying another village. “I’d like to see more companies support things like this,” Blin says.

![Building A Digital PR Strategy: 10 Essential Steps for Beginners [With Examples]](https://buzzsumo.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Building-A-Digital-PR-Strategy-10-Essential-Steps-for-Beginners-With-Examples-bblog-masthead.jpg)