Ask yourself these four questions to figure out if you are fulfilling your full potential

Few topics are simultaneously so celebrated and misunderstood as human potential. On the one hand, we have an influx of near-perpetual articles urging people to unlock or fulfill their own potential, saying essentially that anything else equates to failure. On the other hand, if we ask an average leader or HR professional how to define or explain potential, we are unlikely to get a logical, rational, or scientifically valid answer. And yet, there is a well-established science on human potential, with decades of empirical research resulting in replicable generalizations to predict and explain why some people perform better than others (across different work settings), and why some people develop more than others. What is talent? To understand these findings and their implications, we must start with a basic understanding of talent—since we can’t fully grasp the meaning of potential unless we properly define talent to begin with. Although definitions vary, talent is the ability to display extraordinary levels of performance, irrespective of luck or effort. In any area of competence, measuring the collective output of a team or group of individuals will identify a Pareto-like distribution whereby 20% or so of individuals account for 80% or so of results, output, or productivity. That 20% is comprised by the “vital few,” and while effort and luck may play a role in shaping their performance, in environments where everyone is motivated and incentivized to give their best, consistent differences between the vital few and the rest will largely boil down to talent. So, if talent is how we explain someone’s inclusion among the “vital few,” when luck and hard work aren’t viable explanations, such that talent is basically performance minus effort (the more talented you are at something, the less effort you need to exert to achieve high levels of performance), then what is potential? Potential = nascent talent Potential is talent before you can see it, or nascent talent. That is, talent in the making, or talent waiting to be unfolded. For example, at 25, Mozart, Messi, Picasso, Serena Williams, and Nina Simone displayed such levels of talent that you didn’t even need to have much expertise in their fields of competence to admire their performance and be impressed by their achievements. At age 5, however, they were already giving signs of their extraordinary potential—particularly to the trained eye (e.g., scouts, teachers, mentors, and critics) they appeared to show evidence of an enormous capacity for developing future talent, turning them not so much into a promise, but a rather safe bet. Although most humans lack Mozart’s, Messi’s, Picasso’s, Serena’s, and Simone’s talents—even when we look at the proportionate talents they may exhibit in their own strongest field of competence—the general rule still applies: Their potential is generally not limited to what they have already accomplished, or even their current talents. Indeed, due to lack of incentives, motivation, external politics, and unfairness, not to mention poor career choices (and a lack of accurate constructive feedback), it is rather common for people to “punch below their weight” and spend much of their professional lives not fulfilling their potential. How can you work out if you may be one of them? Consult with brutally honest experts If you want a clear-eyed assessment of your progress, stop asking friends or colleagues who will sugarcoat their feedback. Instead, seek out: Someone who knows your industry deeply (not just a general career coach) Someone who has no problem telling you the truth, even if it hurts Someone who has achieved what you want to achieve and can compare you to real benchmarks, not just make you feel good And, even if you go to the right person for this, it will help if you probe or prompt them in an effective way, namely not fishing for compliments, but rather encouraging them to provide you with a reality check. Ask direct, uncomfortable questions like: “Based on my skills and progress, would you hire me? If not, why?”; “If I keep working the way I am now, where will I be in five years?” Listen. Don’t argue or make excuses. If they say you lack a skill or need to network more, entertain the notion that these suggestions can make you better. And, if you can’t find someone willing to be brutally honest with you, that’s already a red flag. Look at who’s passing you by One of the clearest signs that you’re not fulfilling your potential is when people with similar or even fewer skills surpass you in career, income, or occupational prestige. How to do it? Here are some ideas: Make a list of 5–10 people in your field who started around the same time as you. Compare their progress to yours: Are they getting promoted faster? Are they earning more? Are they building more meaningful industry connections?If they’re ahead, ask why: Is it better skills? More risk

Few topics are simultaneously so celebrated and misunderstood as human potential.

On the one hand, we have an influx of near-perpetual articles urging people to unlock or fulfill their own potential, saying essentially that anything else equates to failure.

On the other hand, if we ask an average leader or HR professional how to define or explain potential, we are unlikely to get a logical, rational, or scientifically valid answer.

And yet, there is a well-established science on human potential, with decades of empirical research resulting in replicable generalizations to predict and explain why some people perform better than others (across different work settings), and why some people develop more than others.

What is talent?

To understand these findings and their implications, we must start with a basic understanding of talent—since we can’t fully grasp the meaning of potential unless we properly define talent to begin with.

Although definitions vary, talent is the ability to display extraordinary levels of performance, irrespective of luck or effort.

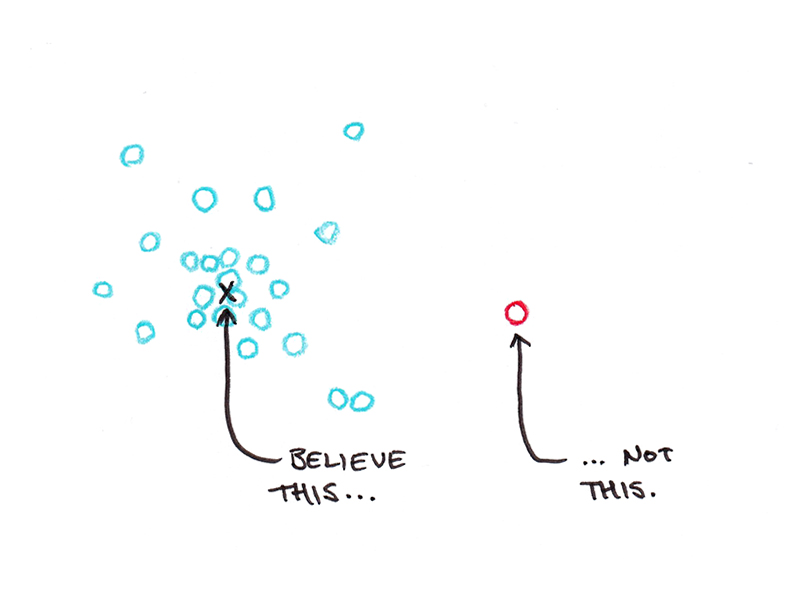

In any area of competence, measuring the collective output of a team or group of individuals will identify a Pareto-like distribution whereby 20% or so of individuals account for 80% or so of results, output, or productivity. That 20% is comprised by the “vital few,” and while effort and luck may play a role in shaping their performance, in environments where everyone is motivated and incentivized to give their best, consistent differences between the vital few and the rest will largely boil down to talent.

So, if talent is how we explain someone’s inclusion among the “vital few,” when luck and hard work aren’t viable explanations, such that talent is basically performance minus effort (the more talented you are at something, the less effort you need to exert to achieve high levels of performance), then what is potential?

Potential = nascent talent

Potential is talent before you can see it, or nascent talent. That is, talent in the making, or talent waiting to be unfolded. For example, at 25, Mozart, Messi, Picasso, Serena Williams, and Nina Simone displayed such levels of talent that you didn’t even need to have much expertise in their fields of competence to admire their performance and be impressed by their achievements. At age 5, however, they were already giving signs of their extraordinary potential—particularly to the trained eye (e.g., scouts, teachers, mentors, and critics) they appeared to show evidence of an enormous capacity for developing future talent, turning them not so much into a promise, but a rather safe bet.

Although most humans lack Mozart’s, Messi’s, Picasso’s, Serena’s, and Simone’s talents—even when we look at the proportionate talents they may exhibit in their own strongest field of competence—the general rule still applies: Their potential is generally not limited to what they have already accomplished, or even their current talents. Indeed, due to lack of incentives, motivation, external politics, and unfairness, not to mention poor career choices (and a lack of accurate constructive feedback), it is rather common for people to “punch below their weight” and spend much of their professional lives not fulfilling their potential.

How can you work out if you may be one of them?

Consult with brutally honest experts

If you want a clear-eyed assessment of your progress, stop asking friends or colleagues who will sugarcoat their feedback. Instead, seek out:

- Someone who knows your industry deeply (not just a general career coach)

- Someone who has no problem telling you the truth, even if it hurts

- Someone who has achieved what you want to achieve and can compare you to real benchmarks, not just make you feel good

And, even if you go to the right person for this, it will help if you probe or prompt them in an effective way, namely not fishing for compliments, but rather encouraging them to provide you with a reality check. Ask direct, uncomfortable questions like: “Based on my skills and progress, would you hire me? If not, why?”; “If I keep working the way I am now, where will I be in five years?” Listen. Don’t argue or make excuses. If they say you lack a skill or need to network more, entertain the notion that these suggestions can make you better. And, if you can’t find someone willing to be brutally honest with you, that’s already a red flag.

Look at who’s passing you by

One of the clearest signs that you’re not fulfilling your potential is when people with similar or even fewer skills surpass you in career, income, or occupational prestige. How to do it? Here are some ideas:

Make a list of 5–10 people in your field who started around the same time as you. Compare their progress to yours:

- Are they getting promoted faster?

- Are they earning more?

- Are they building more meaningful industry connections?

If they’re ahead, ask why: - Is it better skills?

- More risk-taking?

- Stronger networking?

- A better ability to sell themselves?

- A stronger work ethic?

If less talented people are doing better than you, it’s not always because they’re lucky (though luck always helps). More likely, they’re doing something you’re not. Identify what they’re doing better and assess whether you should emulate it—if not, then come up with your own strategy for doing better.

Measure growth in real terms, not effort

Every culture values hard work, yet at the same, when it comes to career success (especially the type that is dependent on other people’s assessment of your performance) you rarely get points for trying hard—only for getting results. Many people feel like they’re working at full capacity, but when you measure actual output, it turns out they’re just spinning their wheels. Perhaps this is why, as Microsoft’s CEO Satya Nadella pointed out, there’s a big discrepancy between how employees evaluate their own work ethic, and how their bosses do, with 85% of managers believing that employees are slacking, while 85% of those employees feeling overworked.

How to improve your self-assessment of both input (work ethic) and output (results):

Instead of asking “Am I working hard?”, ask “What measurable improvements have I made in the last 6 months?,” “What can I do now that I couldn’t do a year ago?”

Track concrete progress in key areas. For example: If you’re a writer, have your pieces improved in quality and impact? Have you increased your actual productivity? If you’re a salesperson, have your numbers improved? If you’re a leader, is your influence on the team growing? Are you actually making your team better, more productive, and so on?

It is often helpful to keep a monthly log of tangible progress on your tasks and deliverables. If you’re not moving forward, adjust immediately—change your strategy, skill set, or work habits.

Find the bottleneck that’s holding you back

Every person who isn’t fulfilling their potential has at least one critical flaw that is limiting them—a “bottleneck” that prevents success, no matter how hard they work.

What you can do: Identify the one thing that, if improved, would unlock the most progress. Be honest—what’s your biggest career liability? Weak technical skills or a lack of expertise? Are you falling behind in your industry? Lack of confidence? Are you bad at self-promotion? Poor networking? Do people with less skill get better opportunities because they know the right people or are better than you at office politics? Inability to execute? Do you start things but never finish? Fix the bottleneck first. For instance, if networking is the issue, don’t waste time improving technical skills—go to industry events and meet the right people first.

In short, though there is no clear-cut answer to the perennial question of whether you are fulfilling your potential or not, you can try to gather credible evidence and data points to at least get a better sense of the likely answer, and pinpoint improvement areas.

A final consideration: If this exercise makes you uncomfortable, that’s a good sign. Just like physical pain is a useful signal that something is malfunctioning and needs to be attended, so too the psychological “pain” we experience when we notice we are not as good as we would like to be opens the gateway and pathways to development and improvement.

![How to Use GA4 to Track Social Media Traffic: 6 Questions, Answers and Insights [VIDEO]](https://www.orbitmedia.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/ab-testing.png)

![Building A Digital PR Strategy: 10 Essential Steps for Beginners [With Examples]](https://buzzsumo.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Building-A-Digital-PR-Strategy-10-Essential-Steps-for-Beginners-With-Examples-bblog-masthead.jpg)

![How Human Behavior Impacts Your Marketing Strategy [Video]](https://contentmarketinginstitute.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/human-behavior-impacts-marketing-strategy-cover-600x330.png?#)

![How to Make a Content Calendar You’ll Actually Use [Templates Included]](https://marketinginsidergroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/content-calendar-templates-2025-300x169.jpg?#)