How to Strategize in an Out-of-Control World

Carolyn Geason-Beissel/MIT SMR | Getty Images During the past few years, company strategies have been disrupted repeatedly by major shocks like the COVID-19 pandemic, the outbreak of war in Ukraine and the Middle East, and breakthroughs in generative AI. In the first months of 2025, a stream of political surprises has been impacting company agendas […]

Carolyn Geason-Beissel/MIT SMR | Getty Images

During the past few years, company strategies have been disrupted repeatedly by major shocks like the COVID-19 pandemic, the outbreak of war in Ukraine and the Middle East, and breakthroughs in generative AI. In the first months of 2025, a stream of political surprises has been impacting company agendas — and further upheavals seem likely.

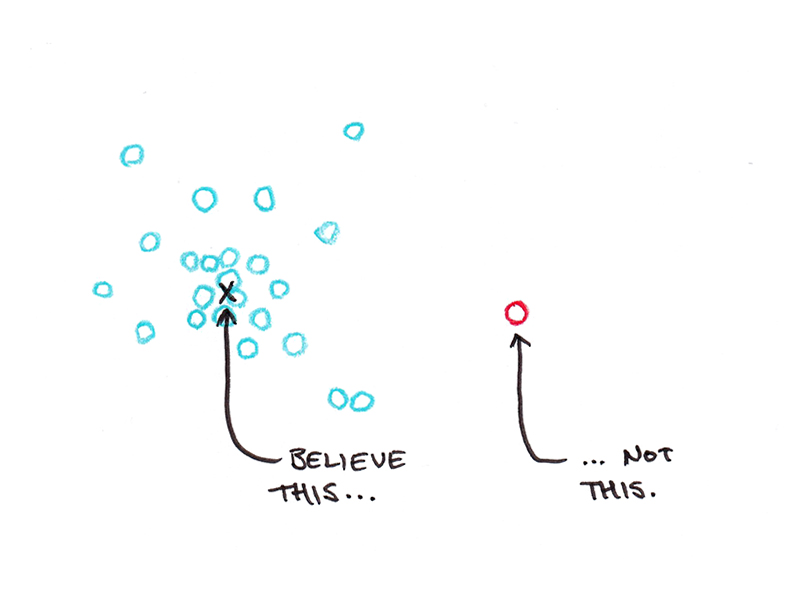

This turbulence is having a real impact on business: Our analysis of nearly 7,000 organizations over a 20-year time frame shows that variance in company profitability can increasingly be attributed to factors that lie beyond the company and its industry. (See “What Shapes Profitability?”) Contextual factors — like geopolitics, technology, and climate — now account for 43% of the variation in the net profit margins of public corporations.

Increasingly, politics is the generator of surprises that reverberate in boardrooms around the world. After the Second World War, countries in most of the Western world embraced economic growth as a primary goal, which went hand in hand with national governments’ support for business activities. Today, with increasing social and political division within many countries and rising geopolitical tensions between them, this support can no longer be taken for granted.

How, then, can CEOs and their teams navigate the current era of political disruption? They must understand and strategize for political risk. Let’s explore how.

Why Current Political Risk Is Different

Political risk is materially different from other risk factors in several important ways.

High frequency. Unlike pandemics or economic shocks, political influence can create significant disruption on a regular cadence. In the digital age, new policies can be announced, modified, and reversed daily, compelling companies to convene war rooms and react in real time.

Multidimensional. Policy changes can affect businesses on multiple dimensions. For example, U.S. executive orders made in January and February have implications across the economy (such as the introduction of tariffs on countries and products), the workforce (such as the rollback of DEI initiatives), sustainability (including the withdrawal of the U.S. from the Paris Agreement on climate action), and more. Furthermore, these influences play out on different time frames: Some require an immediate response, whereas others necessitate longer-term adjustments.

Surprising. Some recent policy interventions seem to have come out of left field (such as the U.S. halting the enforcement of laws banning bribery of foreign officials). Even those that have been signaled in advance are often ambiguous in their details: For example, the introduction of tariffs on imports to the U.S. was to be expected — but when tariffs will be enacted, which countries and products they will affect, and how long they will be in place remains unknown. This uncertainty is heightened as policies are halted, changed, or reversed mere days after their introduction, either by the U.S. executive branch itself or by court decisions.

Less controllable. Contextual surprises like climate disasters or outbreaks of armed conflicts are true black swan events — phenomena that are hard to predict or control. Political factors have historically been more predictable in recent decades because of the broad alignment of politics and economics, with companies being able to exert influence on regulations through lobbying. Now, with policy priorities increasingly being driven by party politics and the protection of national security, the political landscape has become less shapeable by companies.

Engagement-dependent. Many types of business risk — such as demographic shifts — need to be confronted by all players. But political risk is different because its impact on an individual company depends on whether and how a company chooses to interact with it. Political decisions may play out differently, depending on whether, and how vociferously, the business community as a whole decides to engage with them.

Given these considerations, how can companies reflect political risk in their strategies?

Strategizing for Political Risk: Six Steps

We’ve developed a process for strategizing for political risk that can be subdivided into two phases: sensemaking and responding.

Sensemaking

1. Observe the political landscape. To strategize for political risk, executives first need to embrace the idea that focusing only on the company and its market environment is no longer sufficient: The politics section of the newspaper has become as important as the business and finance sections.

Companies need to build the capability to sense policy trends — for example, by engaging with elected representatives and participating in political conferences or delegations. Participating in industry coalitions, which support their corporate members by monitoring relevant regulations and facilitating interactions with political decision makers, is another pragmatic move.

By building on an understanding of relevant political developments, businesses can define and track related KPIs to see early signals that issues are rising in prominence. For example, European food processing and packaging giant Tetra Pak tracks and interprets more than 40 global indicators, including packaging and waste regulations and investments in recycling infrastructure. Going even further, companies could try to gather and interpret weak signals indicating what policies might come next — for example, by inferring public sentiment on relevant issues. Researchers from MIT and Microsoft have shown that social media interactions can be used to predict the outcomes of policy changes with high accuracy.

2. Anticipate the impact of political moves. To prepare for the potential effects of political decisions, companies need to think in terms of scenarios. By extrapolating or combining current political trends — or even as the World Economic Forum has suggested, taking inspiration from science fiction’s descriptions of alternative realities — strategists can draw up possible future states of the political landscape in order to better understand the associated opportunities and risks.

The U.S. Coast Guard has run scenario-planning exercises since the late 1990s in order to anticipate unlikely events and build the capabilities necessary to navigate them. For instance, the scenarios developed after the 9/11 terrorist attacks made it clear to Coast Guard leaders that, in any plausible future, they would want the ability to identify and track every vessel in U.S. waters.

Having outlined a set of relevant scenarios, your organization’s strategists can identify early-warning indicators associated with them — signs that a scenario is becoming closer to reality and that the capabilities to navigate it are becoming more relevant.

Scenario thinking does not just require expertise in identifying, recombining, and extrapolating pertinent trends. Just as critical is the willingness of leaders to engage with improbable but potentially significant future scenarios and let go of their current mental models of the world.

3. Pick your battles. Since political risks may play out differently depending on how a company interacts with them, executives also need to build in an explicit triaging stage to decide whether and how to engage.

Generally, companies should look to avoid unnecessary entanglement in political debates, which can easily result in public or political backlash. Involvement should be focused on political issues directly connected to the core economic activity of the company, making its involvement legitimate and the business a competent contributor to the discussion. For example, car manufacturers should weigh in on vehicle safety regulations or emissions standards.

Moreover, when choosing to get involved, companies should calibrate the intensity of their response. With a fast-moving news cycle, issues will often be overshadowed by the next headline or change with policy shifts, so companies should not overreact. Some of the companies that were among the most active champions of DEI initiatives have also been quickest to reverse course completely, putting their consistency and credibility into question.

In recent years, many businesses have been subject to enormous pressure from their stakeholders to “speak out” or “take a stance.” Reducing this pressure will require resetting expectations toward noninvolvement by adopting institutional neutrality as an explicit policy — and sticking to it for an extended period of time. The University of Chicago’s official stance to be the "home and sponsor of critics" but not a critic itself — a position the university has held since 1967 — is a good example of this. It has helped the university navigate recent political issues better than other academic institutions. For example, while recent U.S.-wide campus protests about the war in the Middle East also extended to the University of Chicago, it did not escalate to high-level resignations or leaders being summoned to hearings in the U.S. House of Representatives.

Among businesses, such neutrality is rare. Berkshire Hathaway is an example of a company that does not take public positions on social issues. While chairman and CEO Warren Buffett is himself outspoken on political issues, he rejects using the company as a vehicle for effecting social change.

Responding

4. Invest in preparedness. Given the unpredictability and multidimensional nature of political risk, it is more important than ever for companies to invest in being better prepared to deal with the often rapid impact of political surprises. This resilience may take different forms — for example, ensuring flexibility to recover critical operations quickly (such as by investing in a diverse supply chain, such that inputs or suppliers can be switched quickly when tariffs are put in place); setting up buffers against potential shocks (such as by diversifying the product portfolio or building up amounts of cash); or creating a modular supply chain (such that the impact of shocks is contained).

For example, consider Ikea’s operations in Russia: After Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, Ikea made significant efforts to localize production and disconnect Russia from the rest of its global supply chain so it could better contain the effects of a shock that might result from a further escalation of conflict. When Russia started a war with Ukraine in 2022, Ikea’s exit from the country was easier than that of peers whose local activities remained deeply connected to their global operations.

Making such moves requires adopting a mindset that balances efficiency with the longer-term considerations of creating value through differential preparedness.

5. Adapt to the new normal. While good preparation can help companies survive turbulence, mere survival is necessary but not sufficient. We often think of shocks as temporary when, in actuality, they often create a new normal. By adapting to this more quickly than industry peers, or by even moving toward new end states proactively, businesses can achieve an advantage. For example, in anticipation of the U.K.’s introduction of a tax on sugary soft drinks, Coca-Cola reformulated its no-sugar offering, Coca-Cola Zero Sugar, to taste more like classic Coke while launching its largest marketing campaign in a decade in the country to promote the drink. This helped Zero Sugar become one of the top five U.K. soft drinks in terms of sales by 2024.

One way to enhance adaptability is to avoid staking out just one specific position in a market in the first place. By developing a platform and fostering a business ecosystem, tech giants have accomplished this: Airbnb, for example, outperformed the hotel industry during the pandemic because it offered a wider range of rental options and was able to quickly pivot to promoting rural listings alongside a work-from-anywhere marketing campaign.

Success here may entail making a bet on the future state of the world. On the business model side, Munich Re’s embrace of climate change modeling as early as the 1970s — decades before insurance peers picked up the practice — is a powerful example. This move established the company as a leader in climate risk modeling, driving its business success when the issue of climate change became more widely appreciated.

6. Selectively shape. While political issues are hard to control, this does not mean that businesses should always be passive. Rather, they should be selective in attempting to shape policies, focusing their efforts on issues that are connected to the core business and where corporate influence is likely to make a difference — in other words, not in matters of party politics or national security.

Besides deciding when to engage, businesses also need to consider how to exert their influence — particularly if they are not the largest or most influential company in their sector. Often, influencing policy-making requires cooperation, such as setting standards within an industry coalition. Classic examples of self-regulation are the rating systems that U.S. movie studios and, later, video game producers adopted to inform consumers about the suitability of content for different audiences. Both systems were initiated in anticipation of regulatory intervention and ended up preempting regulations as well as guiding consumer behavior.

Prerequisites for Navigating Political Risk

To craft strategies that systematically tackle political risk, three prerequisites are key.

Expand your horizon. Executives need to embrace the idea that focusing only on the company and its market environment is no longer sufficient for strategy-making. This is nonintuitive for many executives because, in the post-Cold War era, broader context factors could be assumed to be constants and effectively ignored. Now, strategy must explicitly account for factors beyond the company and its market.

Build the muscle to analyze and triage political risk. New functional expertise in the realm of politics is required to understand the probability and impact of policy interventions, as well as the potential reaction to the corporation’s own actions (or inactions). This means hiring people who are adept at sensing political developments and inferring potential future scenarios. This new functional expertise should be located at the intersection of policy, strategy, and communications work — ensuring that political considerations are incorporated in everyday decision-making. This is more crucial than ever as digital technology dramatically increases the amount of scrutiny on any corporate actions and communications.

Adopt stable positions based on values. Engaging with political and social issues often makes things worse, especially if companies cannot explain their positions or they frequently change them. However, this does not mean that companies should completely forgo engaging or making a positive social impact. To thread the needle, companies should articulate principles that address ethical, social, and political issues. These principles must be specific enough to guide choices, be applicable across multiple plausible situations, and be broad enough to be stable over time, even as political circumstances change. Examples include principles such as “never commit or condone bribery,” “advance technology broadly by open-sourcing patents,” or “minimize environmental impact and embrace regenerative practices.”

In an era of political disruption, it is understandable that corporate leaders might feel overwhelmed and powerless. While political risk is inherently less controllable than traditional business issues, new ways of thinking and acting can reduce adverse impacts. This requires recognizing how political risk is different, developing new capabilities for sensemaking, and being selective about when to engage, adapt, or try to shape the context.

![How to Use GA4 to Track Social Media Traffic: 6 Questions, Answers and Insights [VIDEO]](https://www.orbitmedia.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/ab-testing.png)

![How Human Behavior Impacts Your Marketing Strategy [Video]](https://contentmarketinginstitute.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/human-behavior-impacts-marketing-strategy-cover-600x330.png?#)

![How to Make a Content Calendar You’ll Actually Use [Templates Included]](https://marketinginsidergroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/content-calendar-templates-2025-300x169.jpg?#)

![Building A Digital PR Strategy: 10 Essential Steps for Beginners [With Examples]](https://buzzsumo.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Building-A-Digital-PR-Strategy-10-Essential-Steps-for-Beginners-With-Examples-bblog-masthead.jpg)