Lessons Learned From Outside Innovators

Taylor Callery In the theater of innovation, it is often the outsider who steals the spotlight. Consider Katalin Karikó, the Hungarian scientist who endured years of scorn for her theories about messenger RNA (mRNA). Eventually, her research became the cornerstone of rapid development work on a COVID-19 vaccine — and earned her and collaborator Drew […]

Taylor Callery

In the theater of innovation, it is often the outsider who steals the spotlight. Consider Katalin Karikó, the Hungarian scientist who endured years of scorn for her theories about messenger RNA (mRNA). Eventually, her research became the cornerstone of rapid development work on a COVID-19 vaccine — and earned her and collaborator Drew Weissman the 2023 Nobel Prize in medicine.

Successful disrupters often start on the fringes, dismissed for their unconventional ideas or for pursuing paths others see as fruitless. But there is an upside to their outsider status: Unburdened by the ingrained norms and expectations that constrain insiders, they are uniquely positioned to connect disparate thoughts, see options that others have overlooked, and advance new perspectives that often have the potential of challenging, if not altering altogether, the status quo. Sociologists call this focused naivete — a productive ignorance of entrenched assumptions that enables outsiders to approach problems deemed trivial or unsolvable by experts.

Unfortunately, this freedom usually comes at a cost. The very distance that fuels outsiders’ innovative thinking can also hamper their quest for the backing and recognition needed to bring their ideas to fruition and share them with the world. Without traditional credentials, established networks, or experts’ stamp of approval, the outsider’s journey is often uphill: Along the path to the Nobel, Karikó was demoted and kicked out of her lab space at the University of Pennsylvania, and she was actively discouraged from pursuing work on mRNA. Eventually, in 2013, she joined BioNTech as a senior vice president, after the university denied her reinstatement to the faculty position that she had been demoted from nearly two decades earlier.

Karikó’s experience is emblematic of a broader paradox. As Paul Graham, the founder of Y Combinator, aptly observed, “Great new things often come from the margins, and yet the people who discover them are looked down on by everyone, including themselves.”1 This tension highlights the dual nature of outsider innovation: the ability to break free from conventional thinking while facing skepticism from those rooted in established norms.

How do successful outsiders navigate this paradox? More important, how can organizations remain open to the fresh perspectives that outsiders bring? The challenge lies not only in identifying original thinkers but also in empowering them — amplifying their voices, supporting their efforts, and fostering environments where atypical ideas can take root and thrive.

We have spent over a decade tackling these questions, relying on a variety of qualitative and quantitative methods to chart the remarkable paths of outsiders, which offer important clues as to how individuals, teams, and organizations can expand their creative potential.

Look Outside, but Act Inside

A few years ago, we mapped the intricate web of collaborations among approximately 12,000 Hollywood artists. Our quest was to investigate whether creative success — marked by the attainment of awards that honor cinematic excellence — was concentrated at the epicenter of that web or scattered throughout the industry.2 We found that it was neither those on the extreme fringes nor those at the center who reaped the highest creative rewards. Statistically speaking, those enjoying the greatest creative success resided most often in the liminal borderland, where the center met the periphery — among individuals who straddled both worlds.

This pattern extended to group dynamics as well. As we looked more closely into the data, we found that film crews that blended talents from both the core and the periphery of the massive network consistently outperformed those in groups that emphasized one category or the other. This hybrid social milieu proves to be a more fertile ground for creativity, blending two essential elements for success: fresh ideas and access to influential players who can champion the outsider’s vision.

One way of thinking about this is to picture a climber who is holding tightly to a trusted boulder with one hand while reaching daringly outward with the other. In other contexts, this might mean venturing beyond the boundaries of our customary social circles, reading poetry if our shelves hold only science books, downloading a playlist for an unfamiliar musical genre, or embarking on a journey southward if our travels have always led us north. Grounding in the familiar provides legitimacy while venturing into uncharted territory provides novelty. It’s this dynamic interplay between the secure and the unknown that can spark creativity.

There are many ways companies can stimulate these creativity-nurturing forays into the edges and beyond. Pixar, for example, actively encourages its animators to participate in professional associations, attend academic conferences, and contribute to artwork projects beyond the studio’s confines.3 A former animator and production designer at Pixar, Lou Romano, called this “probably the single most important element that keeps people creative and productive in the workplace.” IDEO, which has pioneered the practice of design thinking in innovation, operates on a similar principle: Employees expect to be tapped for creative work beyond their areas of expertise, believing that an outsider perspective can enrich the creative process.

But it’s not just about sending employees outside of their typical domains — it’s also about bringing the outside in. The National Science Foundation exemplifies this with its use of “rotators.” These scientists, on loan from academic institutions, work at NSF for two to four years and make up about a third of the foundation’s workforce. Recent research has found that this regular influx of outsiders not only increases the NSF’s likelihood of selecting novel projects but also enhances permanent employees’ ability to recognize novelty.4 By straddling the line between insider and outsider, these temporary additions appear to inject fresh perspectives and objectivity into the foundation’s decision-making processes.

Fight Groupthink, and Find an Ally

The NSF’s rotator program, which continually adds fresh perspectives to the working environment, is one approach to combating one of the great dangers of collaborative creativity: the human tendency to conform to a group point of view to maintain social cohesion. A study we conducted in 2014 with Paul Allison from the University of Pennsylvania found that insiders tend to prop up one of their own; outsiders on the creative edge are more likely to gain support or, at the very least, neutral assessments from critics.5 While the grip of conformity is strong, it can easily be weakened: A second voice of dissent can lead the majority to reconsider. One compelling illustration of this idea was included in a popular TED Talk by entrepreneur Derek Sivers, who showed a video in which a lone dancer cuts loose with wild abandon on a hillside. At first, this solo figure is alone, but then a second person bounds up the hill to dance and signals others to join. That support makes the marginal mainstream: As others flood in, a tipping point is reached, and a massive dance party erupts. The video captures the transformative impact that a single ally can have in championing the outsider’s effort and challenges us not just to recast the outsider in a completely different light but to appreciate the value of the first ally who steps forward in support.

Time and again, history has shown us the power of having an ally who supports the ideas of an outsider. Steve Jobs was encouraged by Mike Markkula’s enthusiastic “Yes!” in a sea of venture capitalists’ no’s. Markkula didn’t just provide financial support to the nascent Apple Computer — he threw himself into the enterprise as chairman and, later, CEO, recognizing a kindred revolutionary spirit in Jobs. These allies are often driven by an emotional or cognitive alignment with the visionary outsiders they choose to support.6 As Fabio Zaffagnini, the charismatic marine geologist who journeyed from the wilderness of oceanographic expeditions to leading Rockin’1000, the company orchestrating the world’s biggest rock band, explained to us, “I leaped into this wild venture from the outside track, without a single note of experience in the music industry. Yet, I was backed by a small motley crew of people, even crazier than myself, who bought into my madcap vision.”

Leaders who are willing to ally with outsiders may themselves be outsiders. On the way to establishing a women’s soccer franchise in Los Angeles, Angel City cofounders Kara Nortman and Julie Uhrman faced many rejections from others in the male-dominated soccer sector, where they had no experience. But when they realized that their objectives were really to build a platform for equity and impact, they targeted another sports outsider who shared their enthusiasm for that mission: actress and producer Eva Longoria. Her investment in Angel City attracted additional supporters and ultimately made the marginal mainstream: In 2024, the club was valued at $250 million, representing an unprecedented level of success for women’s soccer franchises worldwide.

Translate the Outside Into Inside Language

Outsiders, particularly those coming from different domains, often bring a distinct perspective and a set of tools that differentiates them. The disadvantage is that they are essentially foreigners, and to persuade others to see things their way, they need to master the language of their new home — no small feat when they haven’t grown up with the locals. To connect with insiders, innovators on the outside must express their ideas in ways that their intended audience can grasp. Our latest experiments put this theory to the test by comparing the impact of different kinds of language on several panels of insiders.7 In one scenario, the innovator used plain language to describe her breakthrough to an audience of professionals. In another, she laced her pitch with the jargon of the inner circle. The result: The generous helping of jargon resulted in insiders giving her ratings that were 20% better than those from the panel that heard the jargon-free pitch.

Of course, mastering the language of the insider may not be easy. Strategically using insiders’ language may be too hard or perhaps feel too inauthentic. In such a case, the outside innovator may need what we call an outside-in translator. Take, for instance, Natura, a Brazilian juggernaut in personal care. Natura collaborates with local Amazonian communities to tap into ancestral knowledge and the region’s biodiversity for fresh product ideas. To accomplish this, Natura relies on cultural translators who are fluent in both cosmetic science and Indigenous people’s knowledge and thus able to weave these insights into innovative, culturally respectful creations.

IBM, too, champions this collaborative ethos with its “technology advocates.” The role is designed to facilitate the translation of external technological ideas into solutions that fit within the framework of IBM’s product offerings. Likewise, at Philips, “cross-pollinators” play a pivotal role, translating insights across departments and ensuring that novel ideas are integrated and understood across the organization. Creating specialized teams and roles in which people serve as translators in this way can align external ideas with internal know-how and capabilities.

Nurture a Receptive Culture

Welcoming outsider perspectives is key to unlocking innovative solutions, but embracing this approach presents two intertwined organizational challenges.

First, there’s the crucial task of bringing outsiders’ ideas into the spotlight. This demands a culture shift because it requires that organizations break away from rigidly centralized decision-making; instead, they must empower employees from all corners to propose solutions, regardless of their rank or expertise. Karim Lakhani’s research on crowdsourced innovation contests has found that the majority of breakthrough solutions spring from minds far removed from a problem’s domain.8

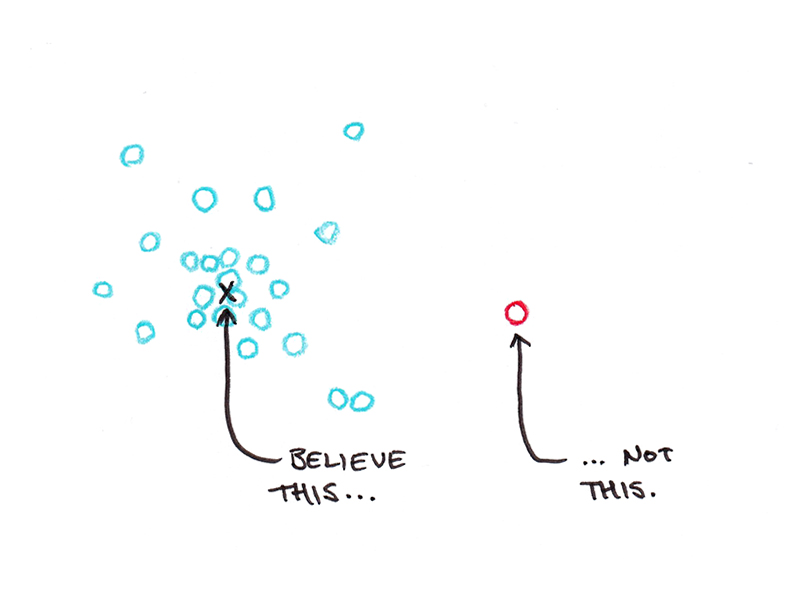

The second challenge is nurturing a culture where these outside ideas can take root, particularly in organizations steeped in a strong group identity. To investigate this challenge, in collaboration with Denise Falchetti from George Washington University, we ran an experiment involving life sciences professionals. Participants were divided into different groups and asked to evaluate the same innovative idea. Beforehand, they were primed to adopt either a collective mindset or an independent perspective. Additionally, while some participants were informed that the idea originated from an insider, the others were led to believe it was the work of an outsider.9 Predictably, when thinking as a collective, the insider idea was preferred and received higher ratings. Yet, when the participants were primed to think on their own, the tables turned dramatically, and the outsider’s identical idea suddenly shone brighter.

This reversal suggests that even a little nudge — like encouraging group members to value unique perspectives and preferences alongside the collective norms and values of the group — can go a long way in reducing aversion to outsiders’ ideas. For example, venture capital firm Sequoia Capital has a rigorous process to minimize groupthink in evaluating potential investments: Each partner scrutinizes business plans and meets with founders separately, allowing them to form unbiased opinions based solely on the merits of the proposal. Only after these independent evaluations are complete do the partners convene to collectively deliberate and make their decisions. This approach fosters a culture of open-mindedness, where contrarian voices are not inhibited but rather are valued as catalysts for innovation.

Another illustration of how a relatively simple intervention can make a company culture more receptive to outside perspectives is the merger of Bank of America with MBNA. Instead of erasing MBNA’s identity, Bank of America made a surprising decision: MBNA’s mottos remained proudly displayed on office walls post-merger, preserving its unique ethos. What’s more, the merged organization adopted not one but two dress codes: formal attire that reflected MBNA’s front-line prowess and a more laid-back style embodying Bank of America’s back-end strengths. This deliberate effort to preserve an outsider identity within Bank of America became the cornerstone for integrating the diverse perspectives, skills, and knowledge brought in by MBNA employees. By fostering an environment that embraced outsider viewpoints, Bank of America gained a competitive edge in its ability to innovate and experiment — a testament to the power of inclusion in driving organizational success.10

Ride the Inflection Points

When someone new knocks on the door of a system — be it a business, an organization, or a team — that outsider is often met with folded arms and wary eyes. However, when pressure mounts, even the most closed systems start to open up to alternative ideas. Our research suggests that the outsider’s vision often comes alive in moments of upheaval — what we call inflection points: make-or-break junctures that upset the status quo, bringing a moment of openness to new ideas.

Karikó’s groundbreaking work on mRNA risked being relegated to the quiet corners of academic libraries after years of rejection by top journals. Although Karikó and Weissman, her co-author and mentor, finally saw the results of their research in print in 2005, it continued to languish unnoticed for a long time. “We talked to pharmaceutical companies and venture capitalists. No one cared,” Weissman said recently.11 “We were screaming a lot, but no one would listen.” The inflection point came when COVID-19 swept across the globe, catapulting their research into the limelight and recast once-scorned Karikó as a central figure in the fight for humanity’s future.

The insights from our research aren’t confined to solitary figures; they apply to the corporate realm as well.12 Take BioNTech, for example — with which Karikó has been closely associated. Virtually unknown outside the small world of European biotechnology startups, it vaulted to prominence by pioneering one of the two first widely authorized COVID-19 vaccines. In the aftermath of the pandemic’s upheaval, BioNTech didn’t just weather the storm: It seized an opportunity, partnering strategically with pharmaceutical titan Pfizer. The partnership granted Pfizer unique know-how while ensuring BioNTech unparalleled access to Pfizer’s vast development infrastructure. The inflection point caused by COVID-19 spurred a surge in such innovation-driving collaborations and ushered in a new era where smaller players, once on the fringes, seized the spotlight with the backing of industry behemoths like Pfizer, Fosun Pharma, and Regeneron.

Sooner or later, every system will experience an inflection point — a decisive moment that cracks open doors to worlds that are usually shut tight against the unfamiliar. For outsiders seeking entry, these rare opportunities demand vigilance. Simultaneously, incumbent company managers armed with this awareness can deftly navigate and take advantage of these pivotal moments, brokering alliances that were once beyond imagination.

Standing up to the collective voice can be daunting, but our research suggests that even the support of one like-minded champion can break the chains of conformity. Our findings also reveal that systems under strain become unexpectedly receptive to new ideas, that receptiveness to outsiders can be nurtured, and that adeptness in speaking the dialect of the inner circle can unlock doors previously thought to be closed. Whether you’re a budding entrepreneur or a seasoned executive, the edge is where some of the greatest opportunities often hide, and harnessing an outsider’s perspective can be your key to unveiling them.

![How to Use GA4 to Track Social Media Traffic: 6 Questions, Answers and Insights [VIDEO]](https://www.orbitmedia.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/ab-testing.png)

![How Human Behavior Impacts Your Marketing Strategy [Video]](https://contentmarketinginstitute.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/human-behavior-impacts-marketing-strategy-cover-600x330.png?#)

![How to Make a Content Calendar You’ll Actually Use [Templates Included]](https://marketinginsidergroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/content-calendar-templates-2025-300x169.jpg?#)

![Building A Digital PR Strategy: 10 Essential Steps for Beginners [With Examples]](https://buzzsumo.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Building-A-Digital-PR-Strategy-10-Essential-Steps-for-Beginners-With-Examples-bblog-masthead.jpg)