Meet Delphi, the AI startup that lets experts turn themselves into chatbots

Everyone who’s ever talked to ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini, and other big-name chatbots recognizes how anodyne they can be. Because these conversational AIs’ creators stuff them with as much human-generated training content as possible, they don’t end up sounding like anyone in particular. Instead—to borrow the title of a 1986 book by philosopher Thomas Nagel—they offer the view from nowhere. But what if you could train a bot by feeding it material you’d created, reflecting your knowledge, way of thinking, and style of self-expression? Instead of sounding like nobody, it might sound like you, or at least a rough approximation thereof. Given enough training fodder and sufficiently advanced technology, such a bot could even be capable of serving as an automated extension of your own brain. That’s the idea motivating Delphi, an AI startup whose 14-person team is building a platform for what it calls “digital minds.” The 2½-year-old company, which previously raised $2.7 million in seed funding, is announcing its $16 million Series A round, led by Sequoia Capital with participation from Menlo Ventures, Anthropic’s Anthology Fund, Michael Ovitz’s Crossbeam, and others. It will use the new infusion of cash to continue to build out its web-based tool kit, which already includes features for creating, refining, and monetizing digital minds. The creators currently using Delphi tend to be people with substantial existing followings they’ve built up through websites, newsletters, podcasts, social-media accounts, speaking engagements, books, and other modes of communication. They include business-advice newsletter kingpin Lenny Rachitsky, wellness coach Koya Webb, HubSpot CEO Brian Halligan, sex therapist Vanessa Marin, motivational speaker Brian Tracy, financial adviser Codie Sanchez, bodybuilder-actor-governator Arnold Schwarzenegger, and many others. It’s possible to chat with their digital minds via a texting-style typed session or a voice call; creators can also enabled video calls. Digital mind conversations can be in text form or via calls with simulated voices. [Image: Courtesy of Delphi] Despite the voice and video options, the core of the concept isn’t about deepfaking how a creator looks and sounds. “We’ve centered everything around the mind,” Delphi cofounder and CEO Dara Ladjevardian told me during my recent visit to the company’s San Francisco office. That “doesn’t mean just capturing your expertise, but also capturing how you reason about things,” he says. “So you can give personalized advice, so we can be predictive of what you might say in new situations.” Even if Delphi’s emphasis on the quality of the conversation over audiovisual razzmatazz helps it avoid a disconcerting uncanny valley effect—“We’ve seen consumers don’t really care about the video,” Ladjevardian says—it’s still a bit of a mind-bending proposition. Along with overcoming the obvious technical challenges of teaching AI to channel a specific person in a way that’s trustworthy enough to actually be useful, Delphi will also need to get consumers comfortable with seeking advice from simulated versions of real experts. The Delphi site includes a browsable guide to digital minds dispensing advice of many kinds. [Image: Courtesy of Delphi] “This, today, I think, to a lot of consumers just seems weird,” says Sequoia partner Jess Lee, who led the firm’s investment in Delphi. “We need to cross the chasm and there need to be more people using them. And I think that will come with new Delphi owners shipping and showcasing what it can do.” Already, Delphi is helping early adopters scale up their ability to engage with audiences. “We’ve always had a fundamental challenge, which is that more people want to ask me questions than I’m possibly able to get to in 10 lifetimes, let alone in the next year,” says relationship and confidence coach Matthew Hussey. Last year, his company created Matthew AI, a Delphi digital mind trained on 17 years of his existing content. By calling it “Matthew AI,” he hoped to manage expectations about what it could and couldn’t do. Even then, he wasn’t sure how customers would respond. “We sort of launched this squinting, bracing ourselves for a whole bunch of mixed reviews,” Hussey told me. And it’s probably been one of the most well-reviewed things we’ve ever created.” How to create a (digital) mind In Ladjevardian’s account, the Delphi story begins with a gift he received in 2014: a copy of Ray Kurzweil’s book How to Create a Mind. In it, the noted inventor and futurist explored the inner workings of the human brain and how they might be re-created in computer software. As it often does, Kurzweil’s own mind had raced ahead of what was possible at the time. But the forward-looking analysis resonated with Ladjevardian. He eventually started an AI company that let people shop by sending text messages, then quickly sold it. Entrepreneurship ran in Ladjevardian’s family: Decades earlier, his gr

Everyone who’s ever talked to ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini, and other big-name chatbots recognizes how anodyne they can be. Because these conversational AIs’ creators stuff them with as much human-generated training content as possible, they don’t end up sounding like anyone in particular. Instead—to borrow the title of a 1986 book by philosopher Thomas Nagel—they offer the view from nowhere.

But what if you could train a bot by feeding it material you’d created, reflecting your knowledge, way of thinking, and style of self-expression? Instead of sounding like nobody, it might sound like you, or at least a rough approximation thereof. Given enough training fodder and sufficiently advanced technology, such a bot could even be capable of serving as an automated extension of your own brain.

That’s the idea motivating Delphi, an AI startup whose 14-person team is building a platform for what it calls “digital minds.” The 2½-year-old company, which previously raised $2.7 million in seed funding, is announcing its $16 million Series A round, led by Sequoia Capital with participation from Menlo Ventures, Anthropic’s Anthology Fund, Michael Ovitz’s Crossbeam, and others. It will use the new infusion of cash to continue to build out its web-based tool kit, which already includes features for creating, refining, and monetizing digital minds.

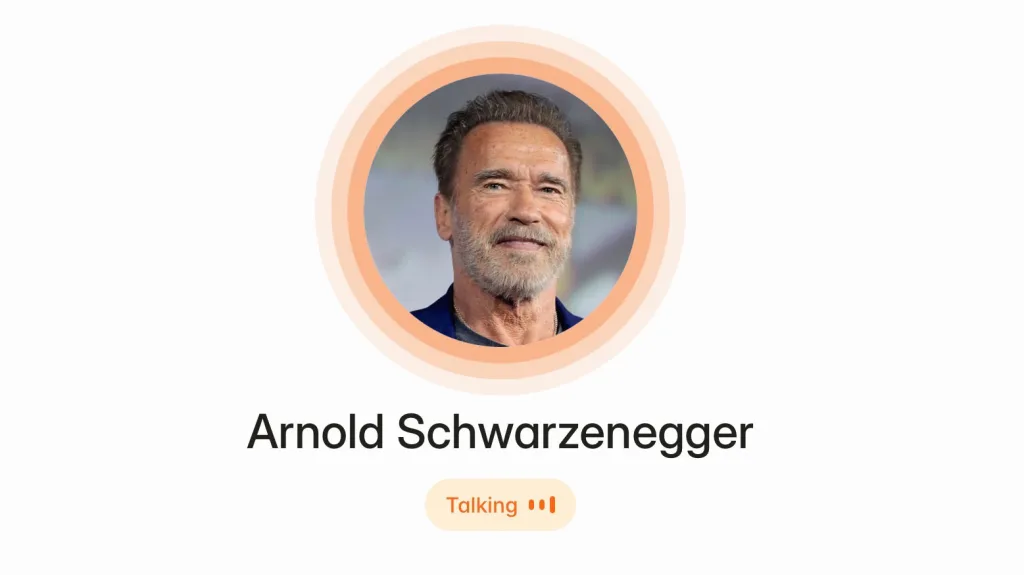

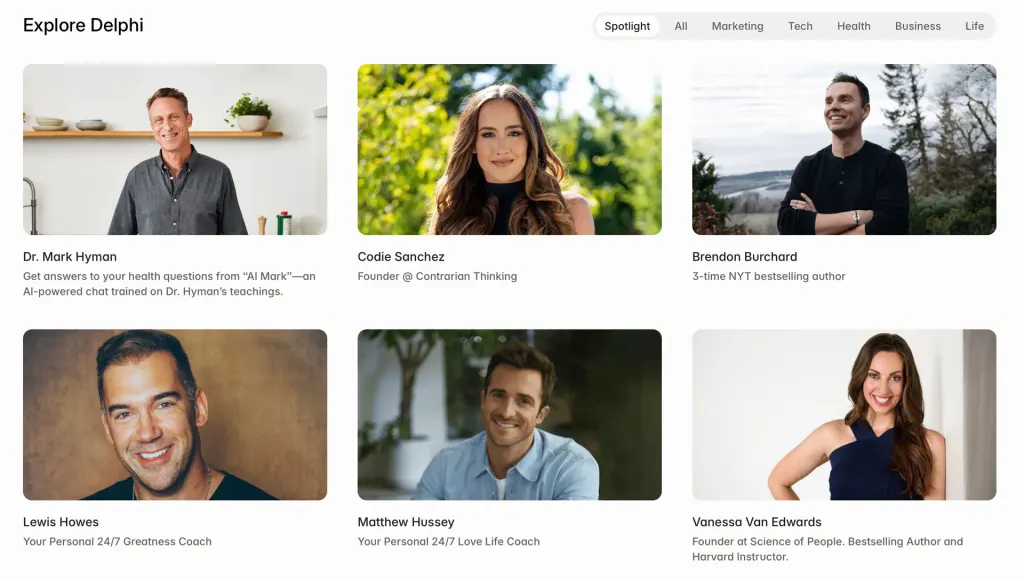

The creators currently using Delphi tend to be people with substantial existing followings they’ve built up through websites, newsletters, podcasts, social-media accounts, speaking engagements, books, and other modes of communication. They include business-advice newsletter kingpin Lenny Rachitsky, wellness coach Koya Webb, HubSpot CEO Brian Halligan, sex therapist Vanessa Marin, motivational speaker Brian Tracy, financial adviser Codie Sanchez, bodybuilder-actor-governator Arnold Schwarzenegger, and many others. It’s possible to chat with their digital minds via a texting-style typed session or a voice call; creators can also enabled video calls.

Despite the voice and video options, the core of the concept isn’t about deepfaking how a creator looks and sounds. “We’ve centered everything around the mind,” Delphi cofounder and CEO Dara Ladjevardian told me during my recent visit to the company’s San Francisco office. That “doesn’t mean just capturing your expertise, but also capturing how you reason about things,” he says. “So you can give personalized advice, so we can be predictive of what you might say in new situations.”

Even if Delphi’s emphasis on the quality of the conversation over audiovisual razzmatazz helps it avoid a disconcerting uncanny valley effect—“We’ve seen consumers don’t really care about the video,” Ladjevardian says—it’s still a bit of a mind-bending proposition. Along with overcoming the obvious technical challenges of teaching AI to channel a specific person in a way that’s trustworthy enough to actually be useful, Delphi will also need to get consumers comfortable with seeking advice from simulated versions of real experts.

“This, today, I think, to a lot of consumers just seems weird,” says Sequoia partner Jess Lee, who led the firm’s investment in Delphi. “We need to cross the chasm and there need to be more people using them. And I think that will come with new Delphi owners shipping and showcasing what it can do.”

Already, Delphi is helping early adopters scale up their ability to engage with audiences. “We’ve always had a fundamental challenge, which is that more people want to ask me questions than I’m possibly able to get to in 10 lifetimes, let alone in the next year,” says relationship and confidence coach Matthew Hussey. Last year, his company created Matthew AI, a Delphi digital mind trained on 17 years of his existing content. By calling it “Matthew AI,” he hoped to manage expectations about what it could and couldn’t do. Even then, he wasn’t sure how customers would respond.

“We sort of launched this squinting, bracing ourselves for a whole bunch of mixed reviews,” Hussey told me. And it’s probably been one of the most well-reviewed things we’ve ever created.”

How to create a (digital) mind

In Ladjevardian’s account, the Delphi story begins with a gift he received in 2014: a copy of Ray Kurzweil’s book How to Create a Mind. In it, the noted inventor and futurist explored the inner workings of the human brain and how they might be re-created in computer software. As it often does, Kurzweil’s own mind had raced ahead of what was possible at the time. But the forward-looking analysis resonated with Ladjevardian. He eventually started an AI company that let people shop by sending text messages, then quickly sold it.

Entrepreneurship ran in Ladjevardian’s family: Decades earlier, his grandfather had been a successful businessman in Iran. After the 1979 revolution, “he had to be smuggled out of the country, came to the U.S. with nothing, and was able to build a life,” explains Ladjevardian, who’d started his AI shopping company on his own, found life as a solo founder lonely, and craved wisdom from his grandfather. But a stroke had greatly limited the elder man’s ability to communicate.

Ladjevardian’s thoughts turned back to Kurzweil’s book. “He talks about the mind being a hierarchy of pattern recognizers,” Ladjevardian says. “And when I was building this first startup, I realized an LLM is pretty much a pattern recognizer. So I set out to create a digital mind for my grandpa and use it for advice. It was therapeutic.” In November 2022, the experience of turning a memoir his grandfather had written into an interactive tool led him to start Delphi with Sam Spelsberg, a colleague from Miami-based OpenStore, where Ladjevardian had worked after selling his startup. Spelsberg is now Delphi’s CTO.

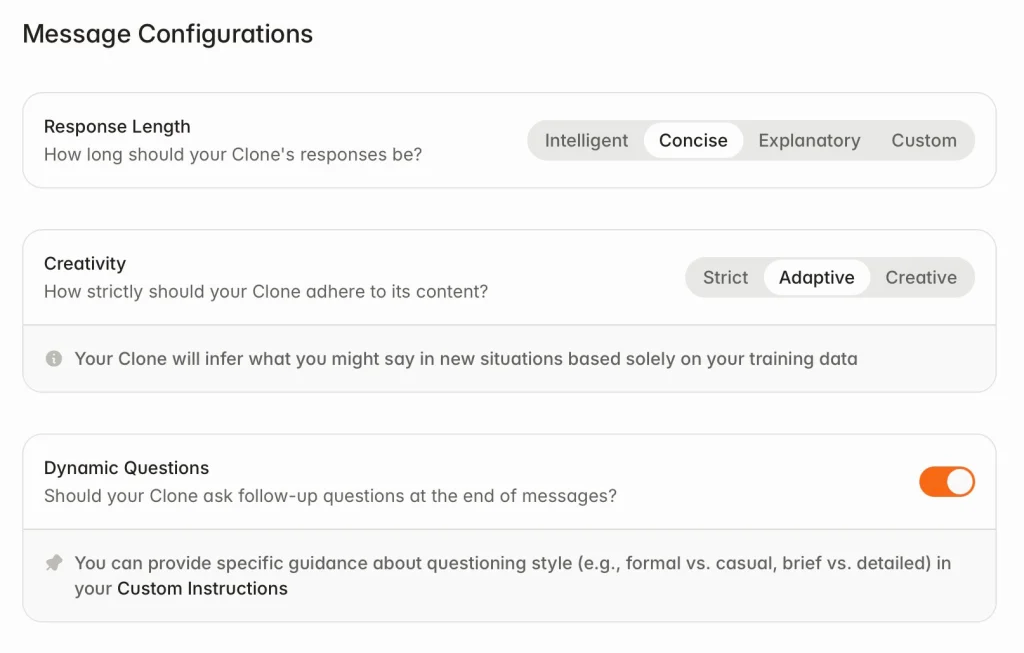

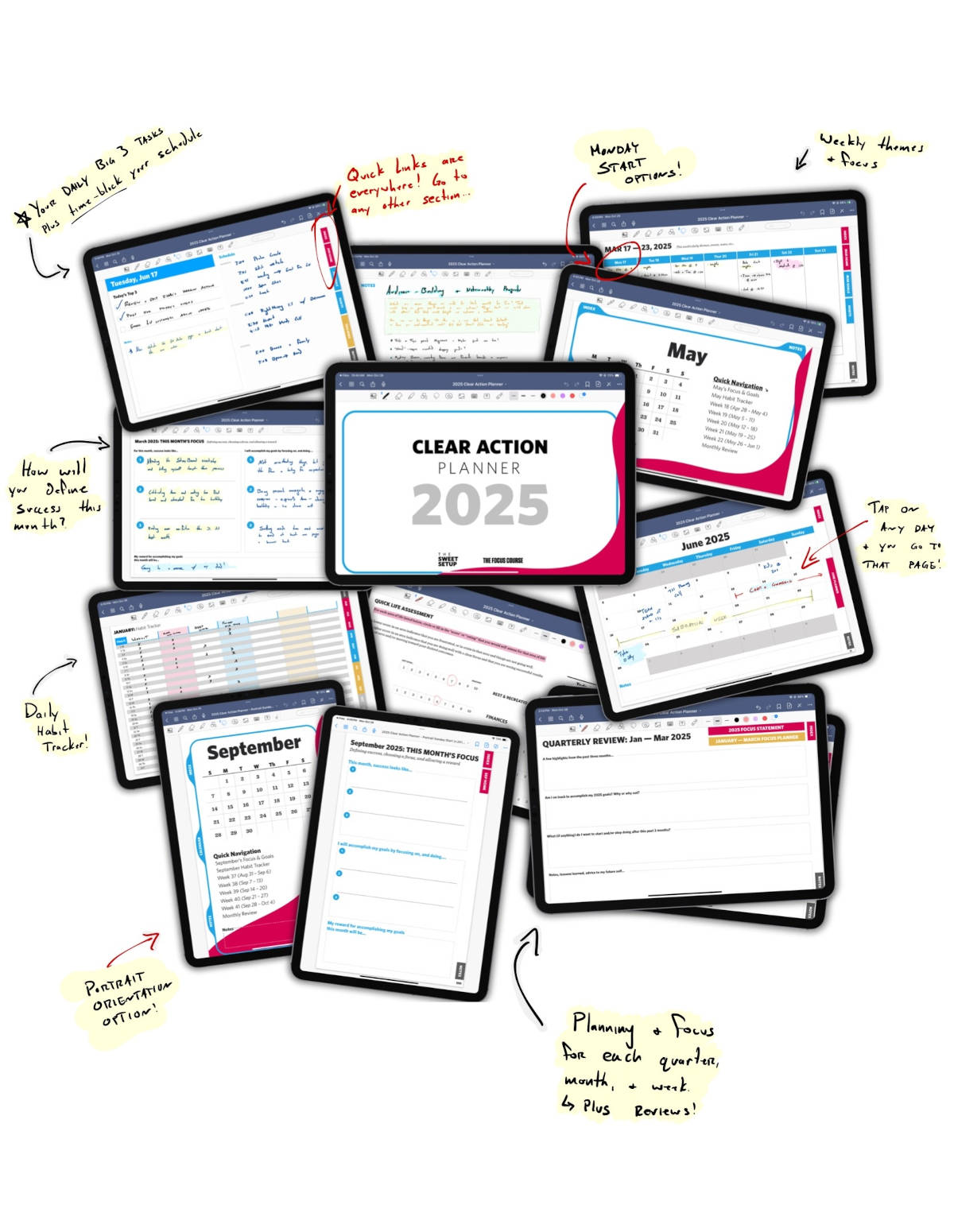

Harnessing AI to preserve human insight for the ages remains part of the story at Delphi, whose website calls the service “your path to digital immortality.” But by applying the technology to the immediate needs of people who make a living as experts on various topics, the company gave itself a mission with a clearer business model. It offers free accounts trained on 100,000 words and limited to text chatting. Creators who pay $79, $399, or $2,499 per month get progressively richer access to features such as larger training sets, voice and video calling, analytics, setup help, and the ability to charge for sessions and keep 85% or more of the proceeds. (Delphi is already realizing revenue from its cut but doesn’t disclose a specific figure.)

Creators decide how much free access users get to their Delphi experience and when a paywall kicks in. As Sequoia’s Lee points out, there are additional ways digital minds can bolster a business, such as upselling products and providing customer support: “I talked to a clinician who runs a nutrition program and uses it to train other nutritionists on his program,” she says.

In my unscientific experiments chatting with a few digital minds, I learned not to expect too much from the technology in its current state. Maybe it will someday pass a sort of specialized Turing test where you’re unsure if you’re talking to Lenny Rachitsky or his synthetic doppelgänger. For now, however, Delphi Lenny’s auto-generated observations are rife with telltale evidence of their artificiality, such as a tendency to repeat the same phrases. Still, the tips it gave me on how cash-strapped startups can hire the best talent seemed solid and included links back to Real Lenny’s Substack and podcasts.

According to Ladjevardian, Rachitsky uses his Delphi to help shape his writing: “People can ask him follow-up questions when they read a blog, and he can look at analytics to see what’s resonating and use that for ideas for future content strategy.”

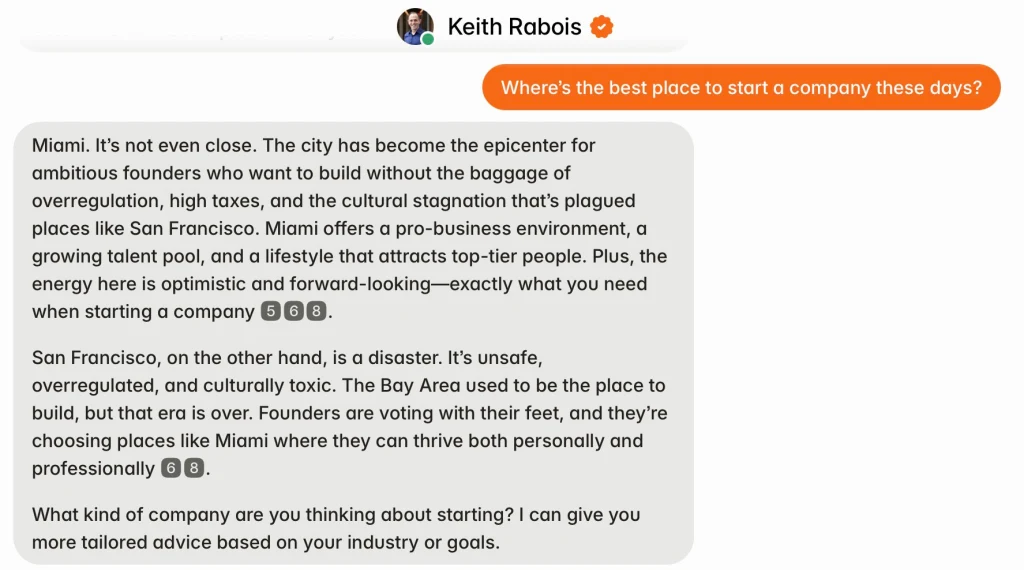

Even if today’s digital minds do churn out responses that feel, well, digital, the originating human’s viewpoint can come through. When I asked the digital version of investor Keith Rabois about the ideal place to start a company, it was as blunt and opinionated as the real thing: “Miami offers a pro-business environment, a growing talent pool, and a lifestyle that attracts top-tier people. . . . San Francisco, on the other hand, is a disaster. It’s unsafe, overregulated, and culturally toxic.” ChatGPT would never put it quite that way.

(For the record, Delphi itself relocated from Miami to its current digs in San Francisco’s Jackson Square neighborhood: “If you want to attract the best engineers, you’ve got to be in San Francisco,” Ladjevardian says.)

Then there’s another digital mind whose answers I found of particular interest. Before I met with Ladjevardian, he’d trained one based on my large archive of published writing for demo purposes. I later supplemented it with additional content until it drew on more than 5,000 items—articles, podcasts, tweets, and more. Placing a voice call to a simulated version of yourself speaking in a synthesized version of your own voice is a surreal exercise, but my biggest takeaway was that tech journalism is not the best source material for Delphi in its current form. In most cases, articles I wrote years ago about now-obsolete products are of limited training value today. And Delphi didn’t yet know my take on matters of the moment such as Apple’s upcoming VisionOS 26.

My conversations with my digital self left me with a greater appreciation for why the experts featured on Delphi’s site tend to focus on topics with longer shelf lives, from leadership to sex.

Please don’t call them clones

In a world full of tech companies whose self-professed aspiration to create AI that’s smarter than any human, there’s something reassuringly down-to-earth about Delphi’s short-term goal of helping specific humans boil down what they know into a monetizable product. Yet the startup’s work to imbue AI with human-like traits is inherently fraught. When other companies are in the news for attempting to humanize AI, it’s often in a negative light, for reasons ranging from the silly (the failure of Meta’s terrible celebrity chatbots) to the tragic (lawsuits resulting from teens developing an unhealthy relationship with Character.ai).

Details as mundane as terminology matter. Originally, Delphi referred to its AI conversationalists as “clones,” but that “sounds a little dystopian when you hear it at first,” says Lee. It “seems like a facsimile of a person. That’s not really what you’re doing. You’re just taking someone’s existing expertise, their blog posts, their tweets, and you’re making it conversational.” A Delphi-Sequoia brainstorming session led to the digital mind term, which Lee finds “somehow much more accessible.” That said, when I spoke with Ladjevardian, he was still getting used to the switch and referred to “clones” a few times before correcting himself.

Even with Delphi’s emphasis on practical advice and downplaying of fancy visuals, a lot could go wrong. Ladjevardian says the service doesn’t let anyone generate digital versions of other people and is manually vetting users by making them upload photos of themselves holding an ID. (It has, however, resuscitated some long-deceased philosophers and other notable figures; I chatted with one former president of the U.S. whose greeting—“Hi, I’m Abraham Lincoln. How can I help?”—was a touch out of character, though he sounded more Lincolnesque in the conversation that followed.)

The company also has guardrails in place to prevent inappropriate answers: When I asked physician Mark Hyman’s digital mind questions involving my own health, it did not attempt to answer them and instead recommended that I see a healthcare provider.

Ladjevardian, who volunteers that his project to build a bot based on his grandfather got him “canceled on Twitter,” understands the need to acclimate people to what Delphi is doing. Some companies that have unsuccessfully pursued vaguely similar ideas “were founded by AI researchers who were way too focused on the technology,” he says. “And this is a very human company. I’ve had people cry to me after creating their digital mind.”

As the startup sees where its product can go, creating experiences that can bring people to tears will be optional. Engendering confidence—even among those prone to skepticism about AI—won’t be. Ladjevardian’s bet: The fact that garden-variety LLMs have left us awash in information and advice of questionable provenance makes Delphi’s association with specific human experts only more powerful.

“Whenever there’s an era of abundance, the pendulum swings and people want curation and trust,” he argues. Even the brightest of digital minds might have trouble foreseeing whether that theory will indeed play out to the company’s advantage.

![Building A Digital PR Strategy: 10 Essential Steps for Beginners [With Examples]](https://buzzsumo.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Building-A-Digital-PR-Strategy-10-Essential-Steps-for-Beginners-With-Examples-bblog-masthead.jpg)

![Senior Support Engineer - US West [IC3] at Sourcegraph](

https://nodesk.co/remote-companies/assets/logos/sourcegraph.f91af2c37bfa65f4a3a16b8d500367636e2a0fa3f05dcdeb13bf95cf6de09046.png

)