This newly discovered cloud is 3,400 times the mass of the Sun—and we almost missed it

4.5 billion years ago the Sun was formed in a swirling cloud of dust and gas called the Solar Nebula. In a paper published by Nature Astronomy journal on April 28th, a team of internationally collaborating scientists proved that another giant molecular cloud hangs only 300 light-years away—making it the closest cloud to Earth. The cloud, named Eos after the Greek goddess of dawn, is so massive that its width would measure about 40 moons side-by-side and its mass is 3,400 times that of the Sun. “This thing was pretty much in our cosmic backyard, and we’ve just missed it,” says astrophysicist and study coauthor Thomas Haworth in an interview with CNN. Why has it taken scientists so long to detect Eos? Molecular clouds are usually detected by tracking light emitted by their carbon monoxide content. For example, the Orion Nebula, which was previously thought to be the closest star forming cloud to Earth, is so bright that it’s visible to the naked eye as a fuzzy smudge under Orion’s Belt. However, this only really works for clouds that have already produced stars. Clouds like Eos that have not yet created any stars do not contain much carbon monoxide. Eos is mostly hydrogen, so it does not emit the signature that scientists typically look for. Because of this, the researchers found Eos by tracking ultraviolet emissions from the hydrogen using data from the Korean STSAT-1 satellite. A spectrograph on the satellite split the ultraviolet light into a spectrum of wavelength components that the researchers were able to analyze. “This is the first-ever molecular cloud discovered by looking for far ultraviolet emission of molecular hydrogen directly,” says lead study author Dr. Blakesley Burkhart in a news release. “The data showed glowing hydrogen molecules detected via fluorescence in the far ultraviolet. This cloud is literally glowing in the dark.” Could Eos make new stars? Stars are formed when clumps of gas and dust in molecular clouds reach a critical mass and then collapse into their own gravity, sucking in more nearby material. Large molecular clouds can birth thousands of protostars. But Eos might be dispersing too quickly to ever produce its own stars. The researchers calculated that the cloud will be destroyed in 5.7 million years’ time. They also calculated the cloud’s photodissociation rate to be around three times the region’s star-formation rate. Even if Eos may never birth a new star, it will provide researchers much deeper insight into the ways that molecular clouds form and dissociate. “When we look through our telescopes, we catch whole solar systems in the act of forming, but we don’t know in detail how that happens,” says Burkhart. “Our discovery of Eos is exciting because we can now directly measure how molecular clouds are forming and dissociating, and how a galaxy begins to transform interstellar gas and dust into stars and planets.” Not to mention, that using the new far-ultraviolet fluorescence emission technique could allow scientists to uncover previously hidden clouds across the galaxy.

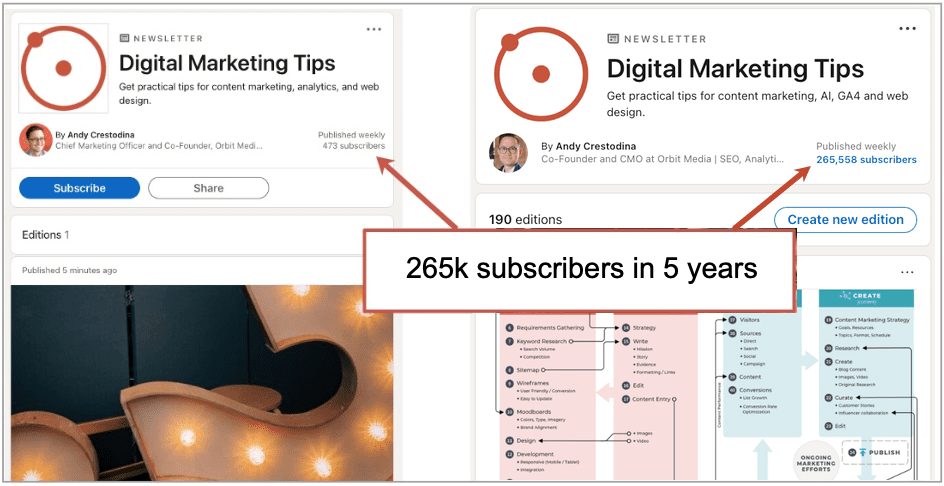

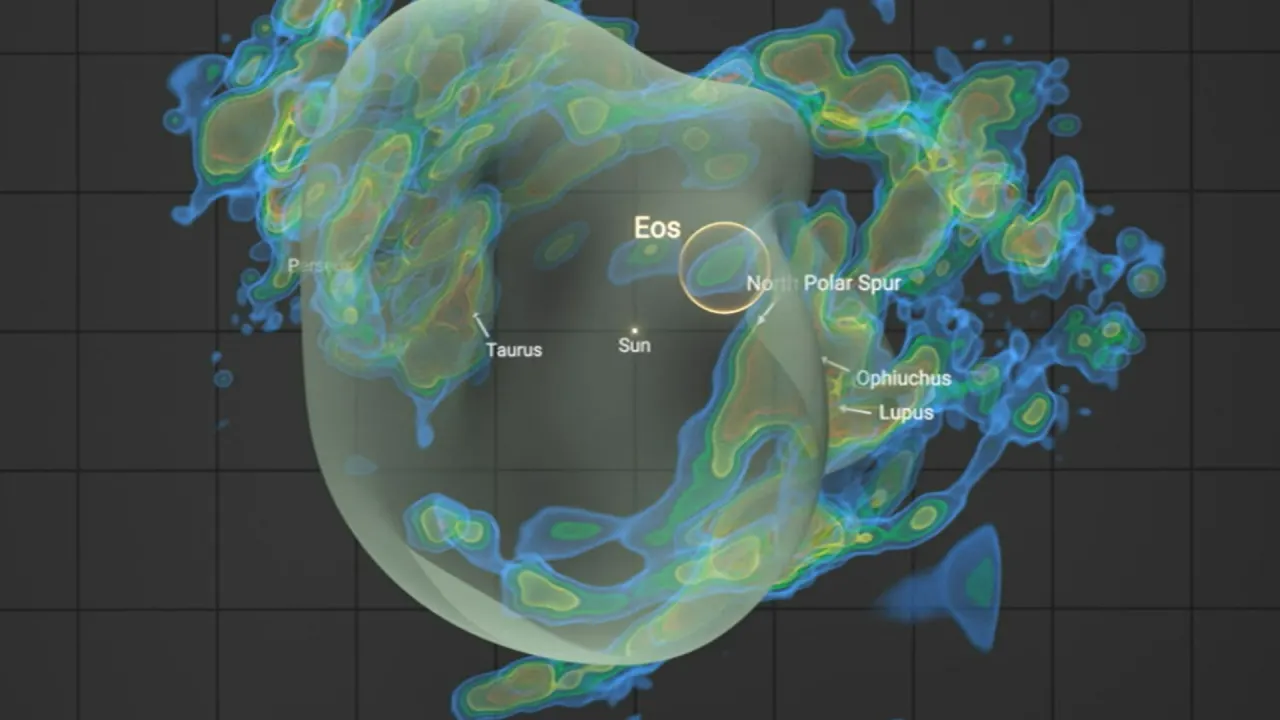

4.5 billion years ago the Sun was formed in a swirling cloud of dust and gas called the Solar Nebula. In a paper published by Nature Astronomy journal on April 28th, a team of internationally collaborating scientists proved that another giant molecular cloud hangs only 300 light-years away—making it the closest cloud to Earth.

The cloud, named Eos after the Greek goddess of dawn, is so massive that its width would measure about 40 moons side-by-side and its mass is 3,400 times that of the Sun. “This thing was pretty much in our cosmic backyard, and we’ve just missed it,” says astrophysicist and study coauthor Thomas Haworth in an interview with CNN.

Why has it taken scientists so long to detect Eos?

Molecular clouds are usually detected by tracking light emitted by their carbon monoxide content. For example, the Orion Nebula, which was previously thought to be the closest star forming cloud to Earth, is so bright that it’s visible to the naked eye as a fuzzy smudge under Orion’s Belt.

However, this only really works for clouds that have already produced stars. Clouds like Eos that have not yet created any stars do not contain much carbon monoxide. Eos is mostly hydrogen, so it does not emit the signature that scientists typically look for.

Because of this, the researchers found Eos by tracking ultraviolet emissions from the hydrogen using data from the Korean STSAT-1 satellite. A spectrograph on the satellite split the ultraviolet light into a spectrum of wavelength components that the researchers were able to analyze.

“This is the first-ever molecular cloud discovered by looking for far ultraviolet emission of molecular hydrogen directly,” says lead study author Dr. Blakesley Burkhart in a news release. “The data showed glowing hydrogen molecules detected via fluorescence in the far ultraviolet. This cloud is literally glowing in the dark.”

Could Eos make new stars?

Stars are formed when clumps of gas and dust in molecular clouds reach a critical mass and then collapse into their own gravity, sucking in more nearby material. Large molecular clouds can birth thousands of protostars.

But Eos might be dispersing too quickly to ever produce its own stars. The researchers calculated that the cloud will be destroyed in 5.7 million years’ time. They also calculated the cloud’s photodissociation rate to be around three times the region’s star-formation rate.

Even if Eos may never birth a new star, it will provide researchers much deeper insight into the ways that molecular clouds form and dissociate.

“When we look through our telescopes, we catch whole solar systems in the act of forming, but we don’t know in detail how that happens,” says Burkhart. “Our discovery of Eos is exciting because we can now directly measure how molecular clouds are forming and dissociating, and how a galaxy begins to transform interstellar gas and dust into stars and planets.”

Not to mention, that using the new far-ultraviolet fluorescence emission technique could allow scientists to uncover previously hidden clouds across the galaxy.

![Building A Digital PR Strategy: 10 Essential Steps for Beginners [With Examples]](https://buzzsumo.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Building-A-Digital-PR-Strategy-10-Essential-Steps-for-Beginners-With-Examples-bblog-masthead.jpg)