Trump wants to kill the wind industry—but new wind farms are still booming

President Donald Trump has a long-standing grudge against wind power. So it wasn’t surprising that when he took office in January, he immediately started to fight the wind industry. In an executive order on his first day, Trump paused leases for offshore wind projects in federal waters. He also paused approvals for wind projects on federal land. At a rally the same day, he said, “We’re not going to do the wind thing. Big, ugly windmills, they ruin your neighborhood.” He declared a national “energy emergency,” but didn’t include wind—the cheapest source of new energy, and an economic and job driver in red states like Oklahoma and Texas—as a possible solution. He previously said he doesn’t want any wind farms built while he is president. It’s a big shift from the Biden administration, which saw wind power as a key part of getting to a carbon-free energy system by 2035. But despite the policy change, some wind developers say their business is still booming. Tech companies are driving energy demand—and they still want renewables “Demand is huge,” says Jim Spencer, president and CEO of Exus Renewables North America, a company that develops, owns, and manages utility-scale renewable projects. The biggest reason: Tech companies are racing to build data centers as AI grows, and need an enormous amount of energy overall. By 2030, global data centers could require more than twice as much energy as they do now, with most of that demand coming from the U.S., according to the International Energy Agency. “I’ve been doing this for 35 years and I’ve never seen such high power demand—wind, solar, storage,” Spencer says. Tech companies were early adopters of large-scale wind and solar projects, and still want to source renewable energy to meet climate goals. But there are also practical and immediate reasons for the demand: Wind and solar are cheaper, in most locations, than building new gas power plants (or restarting closed coal plants, as Trump wants to do). And renewable energy is faster to build. Because of supply chain problems, it can take as long as five years to get some parts needed to make gas turbines for gas power plants. Planning and building new power generation takes years, so new projects that are opening now have been in the works since long before Trump took office—and they’re still mostly renewable. The majority of projects that are currently sitting in the interconnection queue, waiting for approval from grid operators, are also wind or solar. The wind industry still faces challenges That’s not to say that everything is easy for the wind industry now. Even before Trump’s election, wind projects declined last year due to a variety of factors, from high interest rates and permitting delays to supply chain issues and rising turbine prices. Ironically, the Inflation Reduction Act, the landmark bill designed to support decarbonization, also slowed down new projects. Developers were waiting for guidance about which equipment would be considered American-made and qualify for tax credits under the IRA. Because the law was also supposed to keep tax credits in place longer than before, there was less urgency to build. “There was no immediate incentive for developers to start construction right now,” says Stephen Maldonado, research analyst at Wood Mackenzie. Wind installations in 2024 were the lowest in the U.S. in a decade, according to a recent report from Wood Mackenzie. The report also lowered its projections of new wind installations over the next five years by 40%. One part of the projected decline comes from offshore wind and projects on federal land that are now threatened by Trump. Exus, like some other renewable energy developers, doesn’t work on either type of project. But the overall number of turbine orders was also low in the fourth quarter of 2024 and first quarter of 2025. Maldonado attributes that to uncertainty about federal policy. And though Trump didn’t specifically target onshore wind projects on private land, his executive order includes a temporary pause on federal permits for any wind projects. That could affect permits from the Federal Aviation Administration or Fish and Wildlife Service, for example. (Exus says permits are still being issued, though the process is slow, and it’s not clear whether that’s due to policy or the fact that so many federal employees have lost their jobs.) No slowdown yet Despite the challenges, and analysts’ projections, Exus says it isn’t seeing a slowdown in its own work. New renewable projects continue to come online, from a massive solar and storage facility that will soon open in New Mexico to support a Meta data center, to a wind farm that recently opened in Pennsylvania. The company is now working on multiple RFPs for new projects. Buyers haven’t hesitated, Spencer says, even as tariffs have raised the potential for slight price increases. Tariffs will affect renewables less than some other industries, he says, b

President Donald Trump has a long-standing grudge against wind power. So it wasn’t surprising that when he took office in January, he immediately started to fight the wind industry.

In an executive order on his first day, Trump paused leases for offshore wind projects in federal waters. He also paused approvals for wind projects on federal land. At a rally the same day, he said, “We’re not going to do the wind thing. Big, ugly windmills, they ruin your neighborhood.” He declared a national “energy emergency,” but didn’t include wind—the cheapest source of new energy, and an economic and job driver in red states like Oklahoma and Texas—as a possible solution. He previously said he doesn’t want any wind farms built while he is president.

It’s a big shift from the Biden administration, which saw wind power as a key part of getting to a carbon-free energy system by 2035. But despite the policy change, some wind developers say their business is still booming.

Tech companies are driving energy demand—and they still want renewables

“Demand is huge,” says Jim Spencer, president and CEO of Exus Renewables North America, a company that develops, owns, and manages utility-scale renewable projects. The biggest reason: Tech companies are racing to build data centers as AI grows, and need an enormous amount of energy overall. By 2030, global data centers could require more than twice as much energy as they do now, with most of that demand coming from the U.S., according to the International Energy Agency. “I’ve been doing this for 35 years and I’ve never seen such high power demand—wind, solar, storage,” Spencer says.

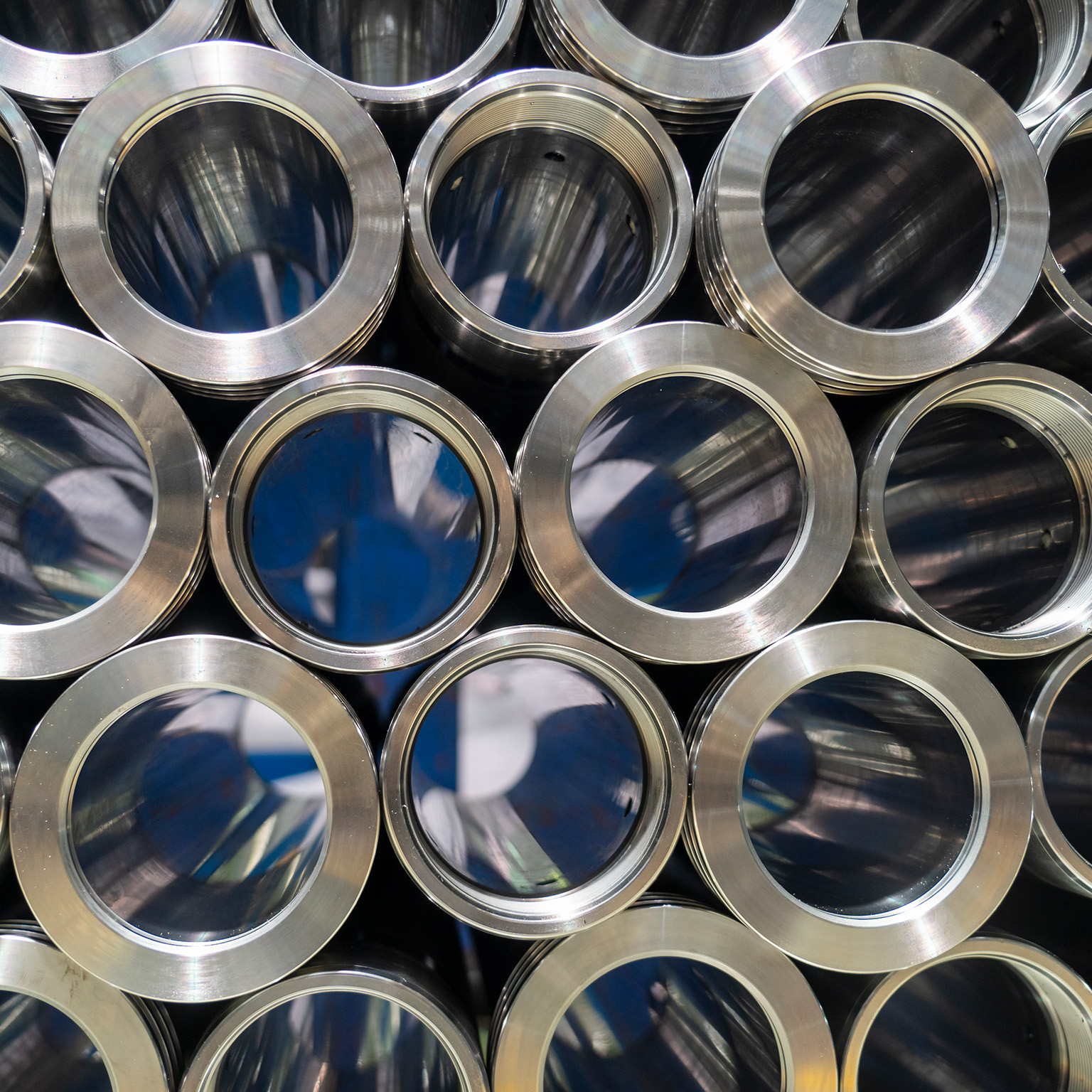

Tech companies were early adopters of large-scale wind and solar projects, and still want to source renewable energy to meet climate goals. But there are also practical and immediate reasons for the demand: Wind and solar are cheaper, in most locations, than building new gas power plants (or restarting closed coal plants, as Trump wants to do). And renewable energy is faster to build. Because of supply chain problems, it can take as long as five years to get some parts needed to make gas turbines for gas power plants.

Planning and building new power generation takes years, so new projects that are opening now have been in the works since long before Trump took office—and they’re still mostly renewable. The majority of projects that are currently sitting in the interconnection queue, waiting for approval from grid operators, are also wind or solar.

The wind industry still faces challenges

That’s not to say that everything is easy for the wind industry now. Even before Trump’s election, wind projects declined last year due to a variety of factors, from high interest rates and permitting delays to supply chain issues and rising turbine prices. Ironically, the Inflation Reduction Act, the landmark bill designed to support decarbonization, also slowed down new projects. Developers were waiting for guidance about which equipment would be considered American-made and qualify for tax credits under the IRA. Because the law was also supposed to keep tax credits in place longer than before, there was less urgency to build. “There was no immediate incentive for developers to start construction right now,” says Stephen Maldonado, research analyst at Wood Mackenzie.

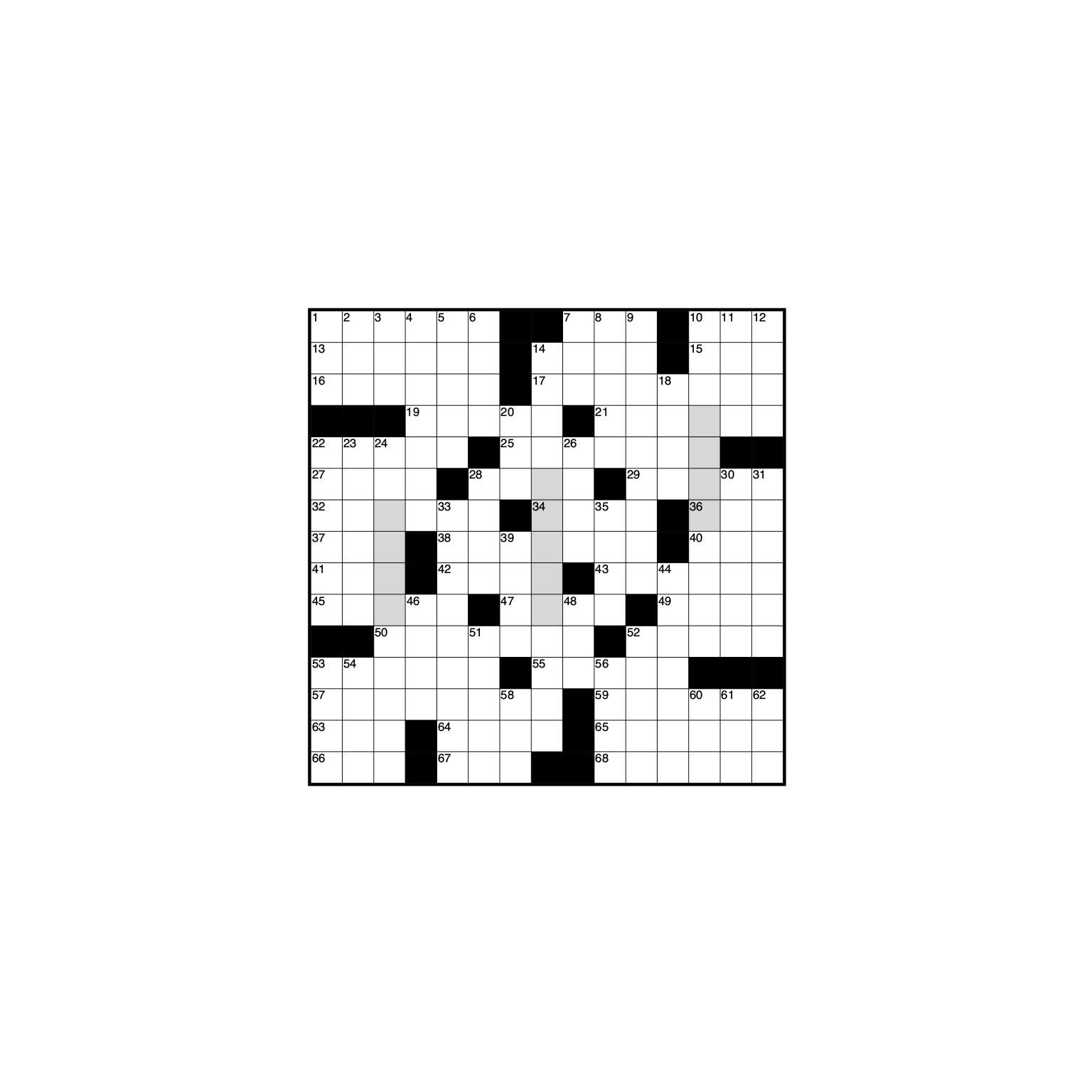

Wind installations in 2024 were the lowest in the U.S. in a decade, according to a recent report from Wood Mackenzie. The report also lowered its projections of new wind installations over the next five years by 40%.

One part of the projected decline comes from offshore wind and projects on federal land that are now threatened by Trump. Exus, like some other renewable energy developers, doesn’t work on either type of project. But the overall number of turbine orders was also low in the fourth quarter of 2024 and first quarter of 2025. Maldonado attributes that to uncertainty about federal policy.

And though Trump didn’t specifically target onshore wind projects on private land, his executive order includes a temporary pause on federal permits for any wind projects. That could affect permits from the Federal Aviation Administration or Fish and Wildlife Service, for example. (Exus says permits are still being issued, though the process is slow, and it’s not clear whether that’s due to policy or the fact that so many federal employees have lost their jobs.)

No slowdown yet

Despite the challenges, and analysts’ projections, Exus says it isn’t seeing a slowdown in its own work. New renewable projects continue to come online, from a massive solar and storage facility that will soon open in New Mexico to support a Meta data center, to a wind farm that recently opened in Pennsylvania. The company is now working on multiple RFPs for new projects. Buyers haven’t hesitated, Spencer says, even as tariffs have raised the potential for slight price increases. Tariffs will affect renewables less than some other industries, he says, because the industry has been onshoring manufacturing for a decade, and the Inflation Reduction Act accelerated that.

During Trump’s first term, wind power kept growing, with a record number of installations in 2020, despite a lack of support from the administration. (The solar industry also grew 128% during his first term.) More coal plants were also retired during Trump’s first term than Barack Obama’s second term, even though Trump had vowed to end the “war on coal.” It’s not inevitable that current policies will derail renewables now.

![Building A Digital PR Strategy: 10 Essential Steps for Beginners [With Examples]](https://buzzsumo.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Building-A-Digital-PR-Strategy-10-Essential-Steps-for-Beginners-With-Examples-bblog-masthead.jpg)

![How One Brand Solved the Marketing Attribution Puzzle [Video]](https://contentmarketinginstitute.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/marketing-attribution-model-600x338.png?#)