38% of Americans live in veterinary deserts—this company wants its telehealth approach to be part of a solution

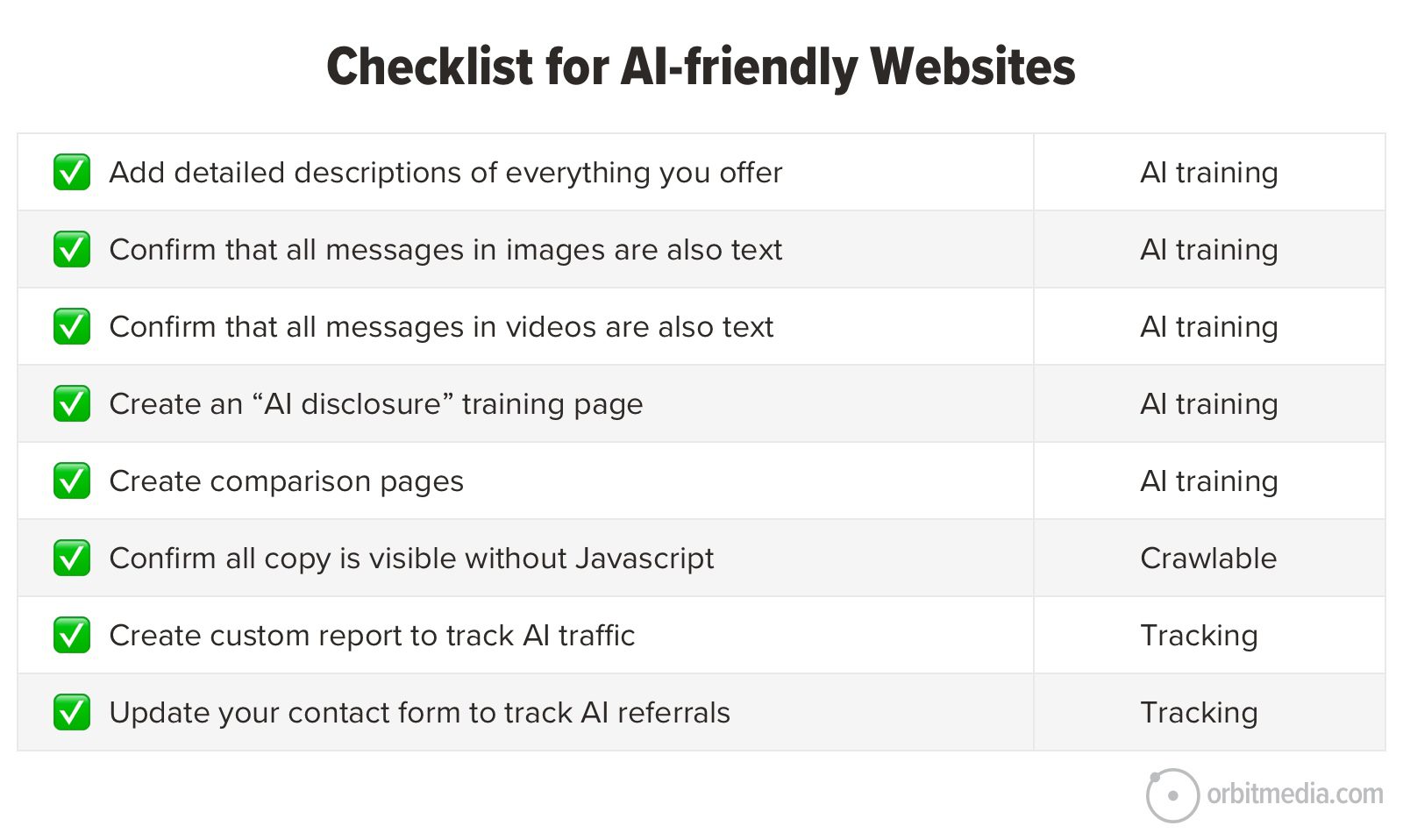

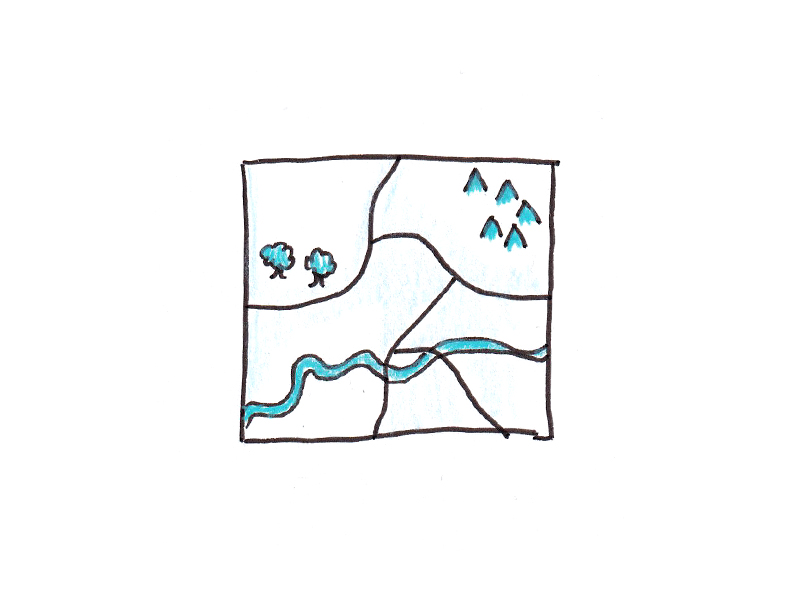

Pet owners know finding a good veterinarian is hard. But in much of the country, finding a vet at all is increasingly tough. A new report released by veterinary telemedicine company Dutch, found that around 38% or 129 million Americans may be living in a veterinary care desert, meaning they don’t have accessible, affordable, or available care for their pets. Dutch’s State of Online Veterinary Care report found that 22% counties nationwide have zero vets per 1,000 households, and pet care is particularly hard to come by in parts of California, Florida, Illinois, New York, and Texas. It’s an issue founder and CEO Joe Spector says likely won’t improve quickly. “There are around 34 veterinary schools in the United States, while there’s almost 400 medical schools,” says Spector, a cofounder of telehealth service Hims. “We just don’t produce that many veterinarians and the veterinarians we do produce drop out [from burnout].” Spector started Dutch because he saw an opportunity for a vet telehealth approach to help address gaps in care. Launched in 2021, Dutch connects pet owners from anywhere in the country to licensed veterinarians over video call and chat for 150 conditions for dogs and cats. With a membership program that allows unlimited consultations starting at $11 a month, the company says it’s seen 40,000 patients since launch, and can save pet owners $700 per year. “These are the folks who otherwise would not see a veterinarian otherwise, because we’ve made it far more affordable,” he says. Cost aside, some veterinary organizations are hesitant to embrace telehealth for pets. The American Veterinary Medical Association—a nonprofit organization representing over 108,000 stakeholders involved with the veterinary profession—says because most telehealth visits are for acute conditions, they aren’t likely to address issues that will eventually require an in-person vet visit. “Not surprisingly, remote areas without a veterinarian often also lack reliable internet access, making the use of telemedicine impractical,” the AVMA says on its site about telehealth vet care. “Mobile veterinary services are a better option not only in terms of access, but also quality of care.” Spector, echoing Dutch’s report, asserts that 90% of veterinary care can be addressed virtually, and notes the company offers additional diagnostic tools for pet owners. “Between overnight testing kits . . . and what we’re able to examine on video, there’s actually a lot that we can do via telemedicine to at least establish that initial treatment plan.” In the four years that Dutch has been active, the company has hired vets in all 50 states and completed more than 40,000 visits. Though Dutch vets can only write prescriptions for patients in 34 states, Spector has been working with state legislators to increase that number. “Change in any field is hard” he says. “But if we can look at human telemedicine, I think at the end of the day we can see . . . how telemedicine has simply become another useful tool that we can use. We don’t have to use it, but it’s yet another option that makes care more affordable and accessible.”

Pet owners know finding a good veterinarian is hard. But in much of the country, finding a vet at all is increasingly tough.

A new report released by veterinary telemedicine company Dutch, found that around 38% or 129 million Americans may be living in a veterinary care desert, meaning they don’t have accessible, affordable, or available care for their pets.

Dutch’s State of Online Veterinary Care report found that 22% counties nationwide have zero vets per 1,000 households, and pet care is particularly hard to come by in parts of California, Florida, Illinois, New York, and Texas. It’s an issue founder and CEO Joe Spector says likely won’t improve quickly.

“There are around 34 veterinary schools in the United States, while there’s almost 400 medical schools,” says Spector, a cofounder of telehealth service Hims. “We just don’t produce that many veterinarians and the veterinarians we do produce drop out [from burnout].”

Spector started Dutch because he saw an opportunity for a vet telehealth approach to help address gaps in care. Launched in 2021, Dutch connects pet owners from anywhere in the country to licensed veterinarians over video call and chat for 150 conditions for dogs and cats. With a membership program that allows unlimited consultations starting at $11 a month, the company says it’s seen 40,000 patients since launch, and can save pet owners $700 per year.

“These are the folks who otherwise would not see a veterinarian otherwise, because we’ve made it far more affordable,” he says.

Cost aside, some veterinary organizations are hesitant to embrace telehealth for pets. The American Veterinary Medical Association—a nonprofit organization representing over 108,000 stakeholders involved with the veterinary profession—says because most telehealth visits are for acute conditions, they aren’t likely to address issues that will eventually require an in-person vet visit.

“Not surprisingly, remote areas without a veterinarian often also lack reliable internet access, making the use of telemedicine impractical,” the AVMA says on its site about telehealth vet care. “Mobile veterinary services are a better option not only in terms of access, but also quality of care.”

Spector, echoing Dutch’s report, asserts that 90% of veterinary care can be addressed virtually, and notes the company offers additional diagnostic tools for pet owners. “Between overnight testing kits . . . and what we’re able to examine on video, there’s actually a lot that we can do via telemedicine to at least establish that initial treatment plan.”

In the four years that Dutch has been active, the company has hired vets in all 50 states and completed more than 40,000 visits. Though Dutch vets can only write prescriptions for patients in 34 states, Spector has been working with state legislators to increase that number.

“Change in any field is hard” he says. “But if we can look at human telemedicine, I think at the end of the day we can see . . . how telemedicine has simply become another useful tool that we can use. We don’t have to use it, but it’s yet another option that makes care more affordable and accessible.”

![Building A Digital PR Strategy: 10 Essential Steps for Beginners [With Examples]](https://buzzsumo.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Building-A-Digital-PR-Strategy-10-Essential-Steps-for-Beginners-With-Examples-bblog-masthead.jpg)

![How One Brand Solved the Marketing Attribution Puzzle [Video]](https://contentmarketinginstitute.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/marketing-attribution-model-600x338.png?#)