Only 5 people could see the world’s newest color. Then Stuart Semple bottled it for everyone

Last week, scientists from the University of California, Berkeley, and the University of Washington shocked the internet by announcing they’ve discovered a new color that can be experienced only when firing a laser into your retinas. Only five people have seen this color, a blue-green shade called “olo.” But over the weekend, artist-provocateur Stuart Semple decided to widen the pool by synthesizing olo into an acrylic paint color he named Yolo. Ironically, Yolo is a color you cannot see—at least not accurately—unless you buy a bottle of the acrylic paint and see it with your own eyes. A 150-milliliter bottle costs $10,000 ($35 if you’re an artist) and is decidedly more accessible than olo. But can it ever be the same? [Photo: courtesy Culture Hustle] Liberating color This isn’t Semple’s first foray into the superlative world of colors. Over the past few years (fueled by various feuds with the artist Anish Kapoor) Semple has created the world’s pinkest pink, followed by the world’s blackest black. In 2021, he hacked Tiffany’s trademarked blue and made his own version, Tiff Blue, which everyone could buy. [Photo: courtesy CultureHustle] A self-described color nerd, Semple has been on a mission to “liberate” color, as he puts it. If olo really is a new color—a claim that’s been contested—he believes more than five people should be able to experience it. “Can’t everyone have a go?” Apparently, they’d like to. “Within minutes, my DMs were crazy,” he says of the requests that poured in from artists and friends alike. Semple spent all night developing Yolo and put it up on his website on Saturday. “My sister messaged me about it the following day, and I was like, ‘already done it,’” he says with a laugh. Within 48 hours of launching Yolo, Semple had sold close to 500 bottles. [Photo: courtesy Culture Hustle] From lasers to pigments The human eye can perceive about 10 million colors known as the visible light spectrum. We see these colors thanks to three kinds of cone cells in our retinas that respond to three specific bands of light: long (red), medium (green), and short (blue). But we don’t just see the world in RGB. Our brains blend signals from these cones to fill in the gaps, conjuring colors like oranges, teals, and purples. To re-create olo, Stuart pored over the recent study, which was published in the scientific journal Science Advances, and pulled the color’s chromatic coordinates. These told him where on the visible light spectrum his own color should sit. Then, he set out on a surprisingly low-tech journey of mixing bases and pigments until he landed on the right formula. “It’s like baking a cake and tasting it,” he says, except instead of his taste buds, he used a spectrometer to see how close each swatch came to olo’s coordinates. But Semple didn’t focus only on pigments—he also looked at texture. In the world of paint, a glossy finish reflects more light than a matte finish, which scatters light in all directions. If you shine a light on a smooth snooker ball, it will bounce off a very small point; but if you shine that same light on a fuzzy tennis ball, the light will get diffused, flattened. Semple’s Black 3.0 paint—the blackest, flattest acrylic paint available on the planet—absorbs 99% of all the visible spectrum. Yolo does the opposite. It reflects 96% of light, but only in the narrow green-blue slice of the spectrum. The other wavelengths are absorbed by the paint. “That’s why it looks like it’s glowing,” Semple says. [Photo: courtesy Culture Hustle] You have to see it to believe it The color you see on this screen comes close, but you can’t fully experience it here, or even in a book, because neither can reproduce the exact wavelength the paint captures: Screens use red, green, and blue pixels; printers use cyan, magenta, yellow, and black. To truly experience Yolo, you have to see it in person, which suits Semple just fine: “I make things for people with eyes, not computers,” he says. Still, the artist claims Yolo is the closest we can get to olo without having a laser fired into our eyeballs. He acknowledges that the litmus test would be to show Yolo to one of those five people, but the scientists did not respond to our requests for comment. If a screen can’t fully capture Yolo, then what kind of color can we expect? Over the course of a 30-minute phone call, Semple used the word weird four times until, finally, he landed on “a weird luminous teal.”

Last week, scientists from the University of California, Berkeley, and the University of Washington shocked the internet by announcing they’ve discovered a new color that can be experienced only when firing a laser into your retinas.

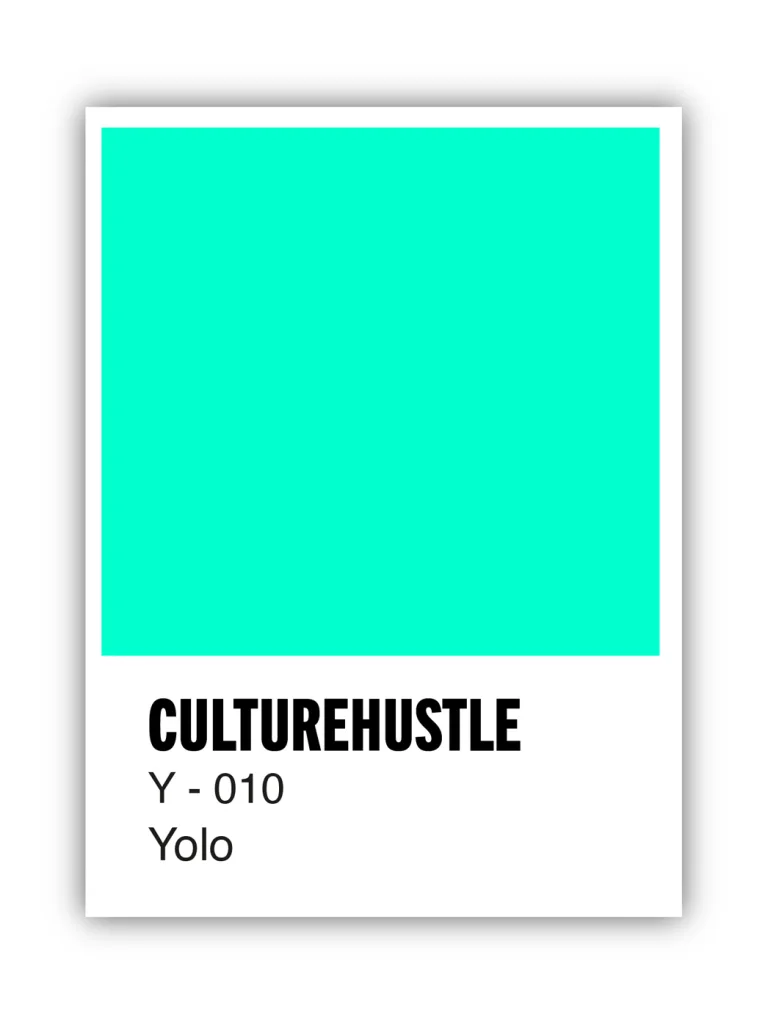

Only five people have seen this color, a blue-green shade called “olo.” But over the weekend, artist-provocateur Stuart Semple decided to widen the pool by synthesizing olo into an acrylic paint color he named Yolo.

Ironically, Yolo is a color you cannot see—at least not accurately—unless you buy a bottle of the acrylic paint and see it with your own eyes. A 150-milliliter bottle costs $10,000 ($35 if you’re an artist) and is decidedly more accessible than olo. But can it ever be the same?

Liberating color

This isn’t Semple’s first foray into the superlative world of colors. Over the past few years (fueled by various feuds with the artist Anish Kapoor) Semple has created the world’s pinkest pink, followed by the world’s blackest black. In 2021, he hacked Tiffany’s trademarked blue and made his own version, Tiff Blue, which everyone could buy.

A self-described color nerd, Semple has been on a mission to “liberate” color, as he puts it. If olo really is a new color—a claim that’s been contested—he believes more than five people should be able to experience it. “Can’t everyone have a go?”

Apparently, they’d like to. “Within minutes, my DMs were crazy,” he says of the requests that poured in from artists and friends alike. Semple spent all night developing Yolo and put it up on his website on Saturday. “My sister messaged me about it the following day, and I was like, ‘already done it,’” he says with a laugh. Within 48 hours of launching Yolo, Semple had sold close to 500 bottles.

From lasers to pigments

The human eye can perceive about 10 million colors known as the visible light spectrum. We see these colors thanks to three kinds of cone cells in our retinas that respond to three specific bands of light: long (red), medium (green), and short (blue). But we don’t just see the world in RGB. Our brains blend signals from these cones to fill in the gaps, conjuring colors like oranges, teals, and purples.

To re-create olo, Stuart pored over the recent study, which was published in the scientific journal Science Advances, and pulled the color’s chromatic coordinates. These told him where on the visible light spectrum his own color should sit. Then, he set out on a surprisingly low-tech journey of mixing bases and pigments until he landed on the right formula. “It’s like baking a cake and tasting it,” he says, except instead of his taste buds, he used a spectrometer to see how close each swatch came to olo’s coordinates.

But Semple didn’t focus only on pigments—he also looked at texture. In the world of paint, a glossy finish reflects more light than a matte finish, which scatters light in all directions. If you shine a light on a smooth snooker ball, it will bounce off a very small point; but if you shine that same light on a fuzzy tennis ball, the light will get diffused, flattened.

Semple’s Black 3.0 paint—the blackest, flattest acrylic paint available on the planet—absorbs 99% of all the visible spectrum. Yolo does the opposite. It reflects 96% of light, but only in the narrow green-blue slice of the spectrum. The other wavelengths are absorbed by the paint. “That’s why it looks like it’s glowing,” Semple says.

You have to see it to believe it

The color you see on this screen comes close, but you can’t fully experience it here, or even in a book, because neither can reproduce the exact wavelength the paint captures: Screens use red, green, and blue pixels; printers use cyan, magenta, yellow, and black. To truly experience Yolo, you have to see it in person, which suits Semple just fine: “I make things for people with eyes, not computers,” he says.

Still, the artist claims Yolo is the closest we can get to olo without having a laser fired into our eyeballs. He acknowledges that the litmus test would be to show Yolo to one of those five people, but the scientists did not respond to our requests for comment.

If a screen can’t fully capture Yolo, then what kind of color can we expect? Over the course of a 30-minute phone call, Semple used the word weird four times until, finally, he landed on “a weird luminous teal.”

![Building A Digital PR Strategy: 10 Essential Steps for Beginners [With Examples]](https://buzzsumo.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Building-A-Digital-PR-Strategy-10-Essential-Steps-for-Beginners-With-Examples-bblog-masthead.jpg)

![How One Brand Solved the Marketing Attribution Puzzle [Video]](https://contentmarketinginstitute.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/marketing-attribution-model-600x338.png?#)