What the Return-to-Office Debate Misses: Employees Are Customers

MIT SMR | Getty Images The ongoing debate about return-to-office mandates is a symptom of a bigger issue. Most companies treat employees as a cost to be managed rather than customers who choose how much of their personal energy and effort to bring to work every day. Your organization likely knows a lot about customer value: […]

MIT SMR | Getty Images

The ongoing debate about return-to-office mandates is a symptom of a bigger issue. Most companies treat employees as a cost to be managed rather than customers who choose how much of their personal energy and effort to bring to work every day. Your organization likely knows a lot about customer value: There is also tremendous value to be generated when employees love their work — or to be lost when they are frustrated or exasperated by it.

The concept of employee centricity isn’t new, but the way organizations have pursued it has been largely simplistic and problematic for various reasons. For example, most employee engagement surveys simply ask workers what they want. Meanwhile, consumer researchers use sophisticated analytics tools, like conjoint, max-diff, and regression analyses, to gain much deeper insights.

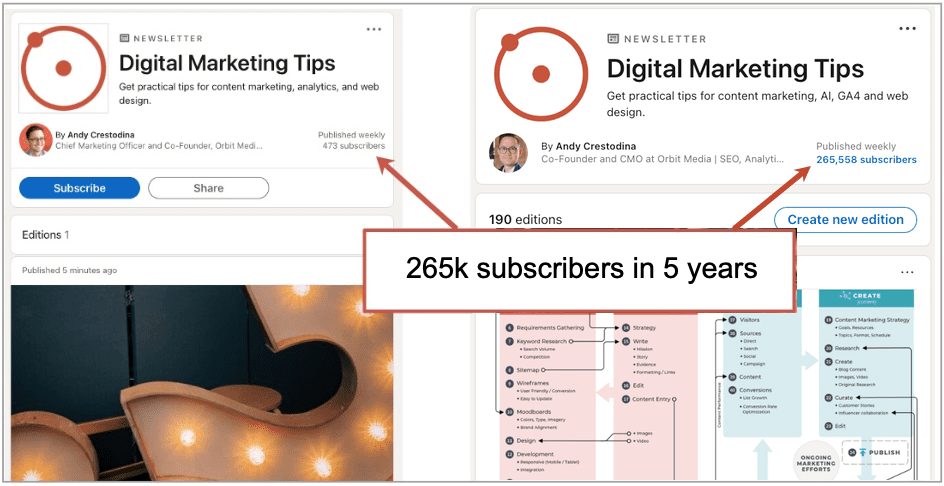

A case in point: In a global survey of more than 11,000 employees, BCG Henderson Institute researchers asked a direct question: “Why would you take a new job?” Not surprisingly, the respondents typically referred to functional aspects of work, such as pay, benefits, perks, and hours. Then the researchers looked deeper, using correlations between satisfaction and retention, to determine what factors predict whether someone is likely to stay in a job. With this more rigorous analysis, emotional factors, such as feeling respected, valued, and supported, dominated the top five. Pay dropped all the way to No. 15 in importance among the list of 22 functional and emotional attributes of work. In other words, pay matters when someone is already looking to leave — it affects where people apply for a new job. But if you want to prevent people from starting that job search in the first place, emotional needs matter most.

Perhaps even more unfortunate, nearly all organizational attempts at employee value delivery treat employees like a monolithic group, rarely recognizing segments with differentiated characteristics and needs. And when they analyze the overall results from annual surveys aimed at better understanding employees’ needs, leaders often use that one-size-fits-all lens. If companies do segment their workforce, they usually do so based on demographic identity — often as part of efforts to support specific communities, such as women.

But our research has shown that segmenting employees based on traditional demographics can obscure critical information about them. Instead, rigorous qualitative and quantitative research and analytics, like those used in consumer research, can reveal what truly differentiates and drives employee outcomes — and what organizations can do to address the various groups’ needs. Without these deep insights, efforts to improve the future of work at your organization, such as improving the hybrid work model, will likely fail.

If your organization thinks a return to the office is part of its future, consider this: RTO mandates go against all notions of employee as customer. Let us count the ways: Blanket office-attendance mandates strip employees of agency, which nearly all employees crave, our research has found. Counting badge swipes highlights a lack of trust, another near-universal need. RTO requirements assume that all employees bring their A-game to all work activities in the office; our research has found that this is generally true for training and community-building but generally untrue for focus and administrative work. We say “generally” because the findings shift when certain populations’ circumstances are considered: caregivers who need more flexibility, people who don’t have space for a work-from-home setup, introverts or neurodiverse people who may struggle with open layout offices, and so on.

Perhaps most importantly, RTO mandates simply miss the mark for leaders and organizations. They don’t improve employee motivation and retention — the cornerstone of any future-of-work strategy. Instead, those goals are best achieved by gaining a deep understanding of what it will take for individual employees to bring their best selves to work every day.

One Sales Force, Multiple Motivations

What can segmenting employees like customers do for an organization? At one U.S.-based manufacturer, the CEO wanted to explore the idea that boosting employees’ enjoyment of their work might boost their performance. (Enjoyment at work matters more than many leaders realize, according to research from the BCG Henderson Institute.) This CEO decided to start with the sales force, aiming for a potential uplift in motivation and consequent uptick in sales. In fact, the company’s initial deep-discovery survey revealed that sales professionals who enjoyed their work were 83% less likely to be looking for a new job and almost four times as likely to be highly motivated at work compared with peers who enjoyed work less.

A further multifactor analysis revealed that the company’s salespeople fell into four categories, each shaped by different career and personal contexts. The segments described below are simplified and illustrative, but they provide a useful starting point for showing how the company came to understand employee needs:

- Roughly 20% of the sales team were builders — people who had been hired within the past three years (after the company underwent a significant restructuring) and were therefore still establishing their place in the organization. They were early in their careers (under age 35), looking to grow, and tended to work in a nonspecialized sales role.

- Jugglers were balancing their work responsibilities with significant personal commitments; these employees made up about 30% of the sales force. They skewed middle-aged and female and tended to be caregivers for children or adults at home. Given the many hats they wore, they had a higher need for flexibility and predictability in their work.

- The mainstays among the sales employees had been with the company for more than 10 years, were over age 55, and were more likely to be male. This group, which accounted for about 20% of the sales staff, were not as likely to be in leadership roles (compared to the averages within the other segments).

- Lastly, we found that the lodgers accounted for roughly 25% of the sales staff. These employees had been with the company for more than three years (pre-restructuring) and were in leadership roles; they had been at the company for some time and had found comfortable spots for themselves in the organization. They were more likely to be women without caregiving responsibilities, and they spanned all age groups.

As we analyzed these segments, we found clear differences among the groups in terms of their job satisfaction, enjoyment levels, and motivation. Builders, the newest employees, were among the most optimistic about their future at the company. They reported always bringing their best self to work and feeling highly satisfied by their role. Their answers suggested that they were eager to establish themselves professionally and to contribute meaningfully.

Jugglers and mainstays had more mixed experiences, with their overall satisfaction closely tied to whether their personal or career needs were being met. Jugglers, who were balancing both work and caregiving responsibilities, often found their day-to-day work challenging as they navigated competing priorities. While they remained committed to their roles, their lower reported motivation may have been based on how well they could integrate their professional and personal obligations. As long-tenured employees, mainstays felt deep loyalty to the organization but sometimes felt underappreciated or frustrated by outdated tools and a lack of new opportunities.

Meanwhile, lodgers reported the lowest satisfaction, with many feeling disconnected and uncertain about their future at the company. Having been with the organization for more than three years but not necessarily feeling a strong connection to its post-restructuring direction, they were struggling to see a clear path forward.

When we explored the reasons behind these differences, it became evident that each group had distinct needs, values, and barriers that shaped their experience on the job. Builders needed structured development, mentorship, and a clear trajectory for advancement. However, their enthusiasm was often tempered by the frustrations of navigating complex processes and waiting on others to move work forward. Jugglers, on the other hand, required greater flexibility and autonomy to balance their work and home responsibilities. The weight of heavy workloads, combined with limited control over their schedules, often left them feeling stretched thin.

For mainstays, the core challenge was access to the right tools, technology, and resources to do their jobs effectively. Their years of experience and deep institutional knowledge positioned them as invaluable contributors, but outdated systems or a lack of recognition sometimes dampened their sense of fulfillment. Lodgers, feeling unmoored in the organization, needed clearer career pathways and more opportunities to reconnect with the company’s evolving mission. Without them, many lodgers found themselves disengaged and uncertain about where they belonged within the organization.

The Art of Cocreating Employee Experience

As important as those insights are, the approach to acting on them is equally important. Improving the employee experience cannot be a top-down or a one-size-fits-all set of initiatives, nor can it be a process in which employees complain to leaders and then expect them to provide solutions. Such scenarios can create or exacerbate an us-versus-them dynamic. Making work work better for employees is best pursued as cocreation with them.

Cocreation involves sharing synthesized findings on employees’ needs (derived from the organization’s qualitative and quantitative employee research) with leaders, managers, and individual employees and then holding cocreation and ideation sessions. Here, individual contributors and managers can work together to identify and prioritize solutions.

At the manufacturing company, frustrations across groups gave leaders a practical place to start. For example, all employee segments except jugglers cited enjoyment at work as one of their highest needs. Additionally, all employee segments cited the combined lack of proper tools, technology, communication, and resources as a major barrier to effectiveness at and enjoyment of work. (This was especially important to mainstays.)

Seeking change, the sales team and its managers participated in several ideation sessions, during which they discussed the research findings, brainstormed, and developed solutions. The teams energetically came up with a set of near-term, implementable solutions. For example, they suggested solving some of the technology issues by having regional leaders train associates on how to effectively use compensation-tracking tools. For the resource issues, employees suggested creating a visible directory of other function leaders, with clear points of contact for sales associates with questions. Regarding the communication issues, employees asked leaders to share major product updates in a weekly email. To address the importance of people enjoying work, leaders committed to regularly and publicly celebrating successes, inviting the sales force to in-person events more often, and creating time for learning more about one another on a personal level when the team got together.

Meanwhile, the points of differentiation among employee segments highlighted more targeted potential interventions. For example, leaders identified an opportunity to improve motivation and satisfaction for jugglers by addressing their burnout through stronger sales support services and greater access to experts who could handle complex questions. Solutions that focused on providing more formal mentorship and stronger recognition programs, as well as opportunities for informal support from leadership, were highlighted by builders and mainstays in particular as ways to provide them with more support and improve their job effectiveness.

Having to wait for others was builders’ biggest barrier to enjoyment and effectiveness on the job. To address this, one solution was to shift from a slow-moving email inbox for general queries to a staffed hotline for salespeople to call with an urgent product or order question. Another idea was to better equip and empower salespeople to take action without input from other business functions. To that end, leaders began sending a weekly digest with product changes and operations updates, and creating clear expectations regarding the types of queries and tasks salespeople could handle independently.

The company is establishing metrics to study the full impact of those interventions, but the excitement generated by the process bodes well for its success. To date, we have spoken with more than 50 of the individual contributors and managers involved in the initiative. They have reported feeling more connected to the organization through this work and believe that they can help improve the results. Throughout the process, sales team members across seniority levels have raised their hands to share best practices on individual teams to scale them at the company level, and agreed to co-own the rollout of these solutions. Many sales team members have also expressed a belief that taking small steps today through these targeted interventions can open the door to more ambitious, longer-term improvements.

And, of course, it’s not a one-and-done scenario. Inspired by these initial findings, leaders are planning to continue to talk with their employees, learn about their experiences, cocreate improvements to test together, and work together to adjust the solutions over time.

These types of data-driven, employee-cocreated work solutions are a far cry from a one-size-fits-most, top-down RTO mandate. Other companies learned this lesson early in the post-work environment.

Consider Mr. Cooper Group, a U.S.-based home loan servicer. After the COVID-19 pandemic, the company was about to bring all of its employees, including call center staffers, back into the office and physical call centers. But instead, leaders paused and took the time to deeply understand what their employees needed to thrive at work. Leaders found that employees felt more trusted, valued, and respected when they could work from home, plus they saved a meaningful amount money on clothing and transportation.

Working together, employees and leaders cocreated a new working model they called “home-centric.” The default was for people to work from home, but employees would come together for onboarding, training, and culture-building activities. The company invested in upskilling front-line managers to be able to coach, mentor, develop and inspire their home-centric teams. Leadership also invested in technology to enable managers to listen in on customer calls remotely in order to coach and train their call center employees.

At Mr. Cooper Group, home-centric looks different for every team. While the call center team works from home, other groups may have different arrangements based on their specific needs and team norms. This flexible approach ensures that all employees, regardless of their team, can thrive in their particular work environment. And while the mortgage industry has had a tumultuous few years, Mr. Cooper Group has maintained employee morale and doubled its market cap since implementing its home-centric model.

How Leaders Can Bring Employee Centricity to Life

Most organizations already have what they need to unlock employee motivation. The work of customer-facing functions (such as marketing) typically includes deep customer discovery, segmentation, personalization, big data analytics, design thinking, and customer journeys. When an organization does similar work to study employees and their day-to-day job experiences, leaders can zero in on how best to shape work to motivate and retain their people.

Here are some specific ways to get started:

- When considering actions to improve employee motivation, productivity, and enjoyment, identify which needs are universal across segments, and start there — but don’t end there. Consider what types of actions will be differentially effective for your segments based on their needs.

- When analyzing the potential impact of changes, consider what the value of improved employee motivation and retention will be to both external customers and the company’s bottom line. For example, in one consulting engagement, the company we worked with found that employees saved two to four hours a week when work was redesigned to be more enjoyable and less toilful — which freed up time that could be reinvested in multiple ways.

- Shape the work to fit different employee needs. For employees seeking advancement, you can provide opportunities to upskill on new technologies, which can open doors to new types of roles. Give the people who are most focused on having a supportive and connected workplace the chance to help shape mentorship and employee recognition programs. Ensure that those balancing work and caregiving responsibilities have flexible work options.

- Further investigate who your less-motivated workers are. They may be great employees who need a joy jolt — or people who aren’t the right fit. You won’t know until you dig deep.

- When rolling out new technologies like generative AI, which has already proved to be challenging for many organizations, consider your different employee segments and adapt the approach accordingly. When the BCG Henderson Institute was rolling out GenAI to BCG’s administrative staff, it found that employees who had the most desire to advance their careers were more open to diving into GenAI tools. Among “lifer” colleagues, who wanted to stay in their role for the long term, we had to adapt tool usage so as to not take away the specific parts of each person’s day-to-day work that they enjoyed the most.

- Upskill, resource, and support managers — especially front-line managers — so that they can identify the employee segments on their own teams. Managers will also want to explore the individuals’ motivations and goals. Just as sales reps are trained to recognize different types of customers (price-motivated versus status-motivated versus quality-motivated versus relationship-motivated) and adjust their sales pitch accordingly, managers need to understand the different team members and adjust their own management styles and work routines accordingly. This way, managers can deliver what each team member needs to thrive every day. HR and line-of-business leaders will need to work together to craft segments and personas that accurately reflect the workforce.

- When building career maps and pathways, consider different types of employees. For example, some employees crave a path to leadership, while others may want to deepen their technical expertise over time, and others may want to stay and excel in a particular role. Employers need to invest in ways to recognize and support folks who want very different paths.

These actions, focused on treating employees more like customers, stress deep discovery, segmentation, and cocreation. This approach should not only improve employee motivation and effectiveness but also create a positive spillover effect on overall organizational performance.

To track progress toward that goal, leaders must define clear metrics that measure the impact of segmenting employees — both on employee sentiment (like motivation, perceived effectiveness, attrition, and satisfaction) and on key business outcomes (like revenue growth, productivity, and customer satisfaction). It’s time for all organizations to up their game when it comes to employee-centricity.

![Building A Digital PR Strategy: 10 Essential Steps for Beginners [With Examples]](https://buzzsumo.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Building-A-Digital-PR-Strategy-10-Essential-Steps-for-Beginners-With-Examples-bblog-masthead.jpg)