AI studied Hong Kong’s streets. Here’s what it learned about making cities more walkable

Some places are simply nicer to walk through than others. Compare a tree-lined path along the Seine in Paris to the side of a six-lane highway in Tallahassee, Florida, and the differences are obvious. But what exactly makes a place walkable is a matter of some debate. Those of the urbanist persuasion might point to a place’s density or mix of land uses. Platforms like Walk Score might favor accessibility, proximity, and travel times. One person might want to have a café within walking distance, while another might want the safety of working streetlights. Conditions are varied, and uneven. To better understand what exactly makes a place walkable, the architecture firm Perkins Eastman turned to a novel form of data analysis. In a new study, the firm combined qualitative pedestrian preference surveys, visual streetscape imagery from Google Street View, artificial intelligence, and computer vision to identify the specific type and mix of urban design elements that most influence people’s walking habits. Focusing specifically on older adults, the study is a window into the ways cities enable pedestrian activity, and how they can encourage more. [Image: ©Perkins Eastman] What the walkability study found is that people prefer to walk in places with a higher proportion of several basic streetscape elements, including benches, shade trees, sidewalks, and crosswalks. When those elements are provided in combination with one another—plentiful benches and crosswalks, for example—people are likely to walk even more. [Image: ©Perkins Eastman] The study was based in the Kowloon district of Hong Kong, where a decennial survey collects detailed information from more than 100,000 pedestrians about the experience of walking through this part of the city. This survey data was analyzed alongside Google Street View imagery of the district to see what streetscape elements were predominant in places people reported being most likely to walk. This analysis led to a set of urban design guidelines that suggest ways of making more spaces more walkable. [Image: ©Perkins Eastman] The resulting study, “Are these streets made for walking?: How visual AI can inform urban walkability for older adults,” was led by Haozhou Yang, a student at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design who was a design and wellness research fellow at Perkins Eastman from 2023 to 2024. He says most previous walkability studies rely on zoomed-out data from geographic information systems (GIS), inferring walkability from data points like the existence of sidewalks or a neighborhood’s proximity to retail. “They’re not from the human perspective,” Yang says. “This [study] really puts the elements people encounter every day at the front.” [Image: ©Perkins Eastman] Google Street View offered Yang a deep pool of data about the real world conditions experienced by pedestrians in Hong Kong. His study used 32,512 images from Google Street View, separated throughout the district at 10-meter intervals. Machine learning techniques then broke each image down to identify individual streetscape objects within the frame and how much space they accounted for. One image might show tree canopy covering roughly half the image and sidewalk making up about a quarter. Other images show benches and walls. Still others highlight crosswalks and how much space is dedicated to car traffic. “With new AI computer vision, we can really understand the quantifiable amount of those elements in the open environment,” Yang says. By focusing in on seven categories of streetscape elements—sidewalks, streetlights, trees, crosswalks, benches, walls, and windows—Yang and collaborators from Perkins Eastman were able to draw correlations between the presence and combination of those elements in places with high rates of pedestrian activity. These correlations then informed a set of urban design guidelines developed by Perkins Eastman’s senior living team. These guidelines include combining street furniture with greenery and open space, pairing crosswalks with improved street lighting, and increasing the social interactivity of a space by having more benches in areas with a higher amount of street-facing windows, balconies, and patios. The study draws these connections through the lens of improving walking conditions for older adults, with the health and social benefits that come from being more mobile and independent. But the implications of the research are much broader, according to Perkins Eastman senior living principal Alejandro Giraldo. “These are things that are universal design,” Giraldo says. “It’s not just addressing the seniors. It absolutely will, but it’s also addressing people with mobility issues or children.” Yang says that even though the data in this study is from Hong Kong, AI enables the model to be tuned or tweaked to the conditions in other cities, informing what might improve the walkability of that stretch along the Seine River or the side of that

Some places are simply nicer to walk through than others. Compare a tree-lined path along the Seine in Paris to the side of a six-lane highway in Tallahassee, Florida, and the differences are obvious. But what exactly makes a place walkable is a matter of some debate.

Those of the urbanist persuasion might point to a place’s density or mix of land uses. Platforms like Walk Score might favor accessibility, proximity, and travel times. One person might want to have a café within walking distance, while another might want the safety of working streetlights. Conditions are varied, and uneven.

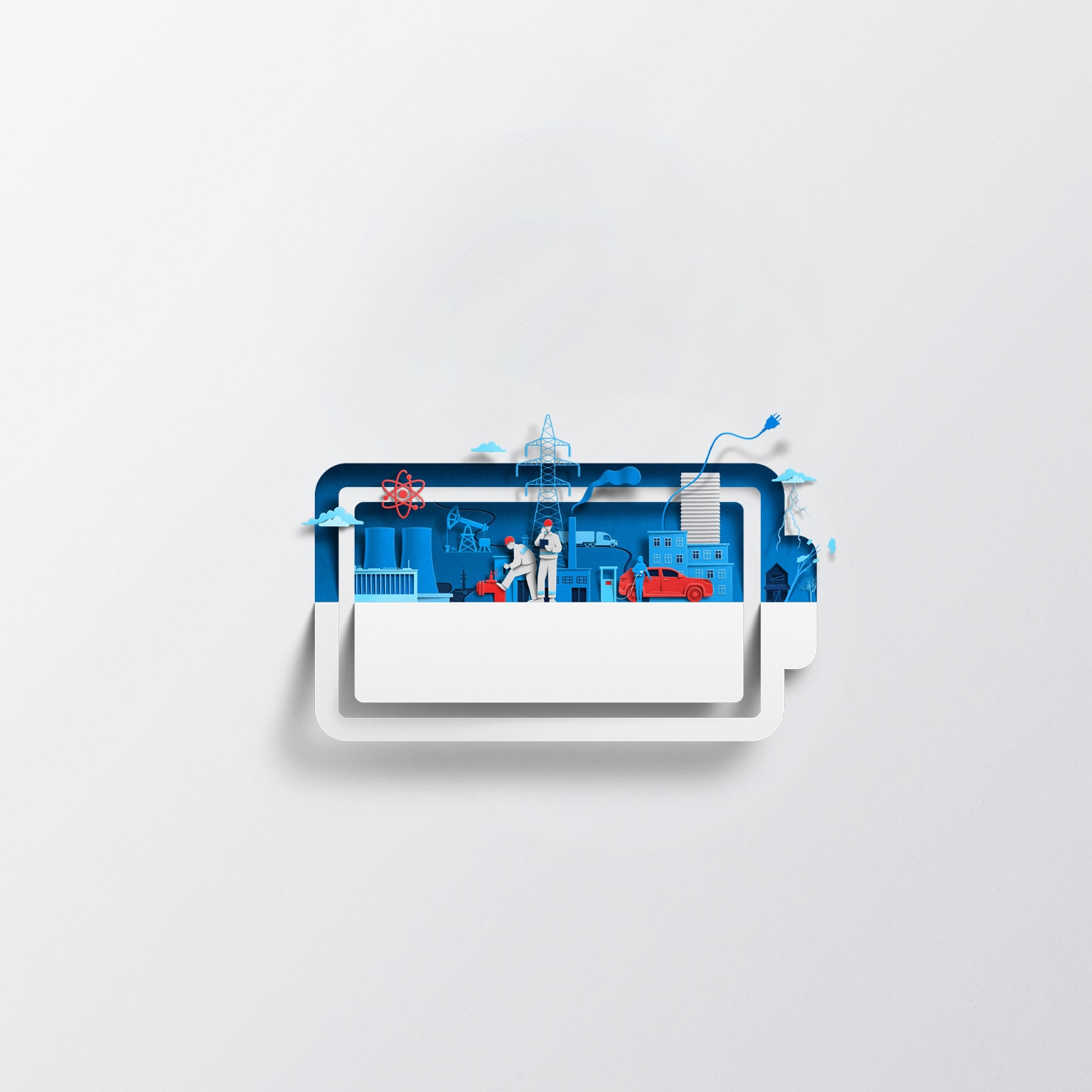

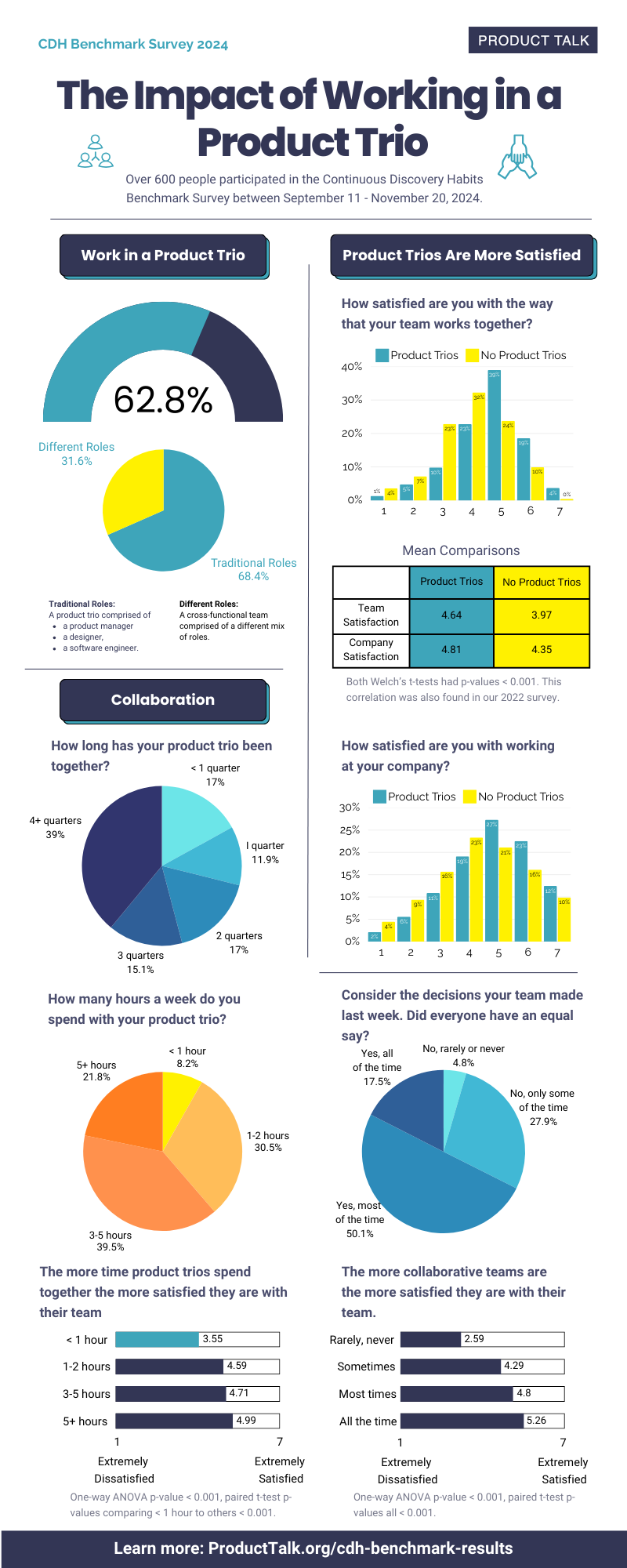

To better understand what exactly makes a place walkable, the architecture firm Perkins Eastman turned to a novel form of data analysis. In a new study, the firm combined qualitative pedestrian preference surveys, visual streetscape imagery from Google Street View, artificial intelligence, and computer vision to identify the specific type and mix of urban design elements that most influence people’s walking habits. Focusing specifically on older adults, the study is a window into the ways cities enable pedestrian activity, and how they can encourage more.

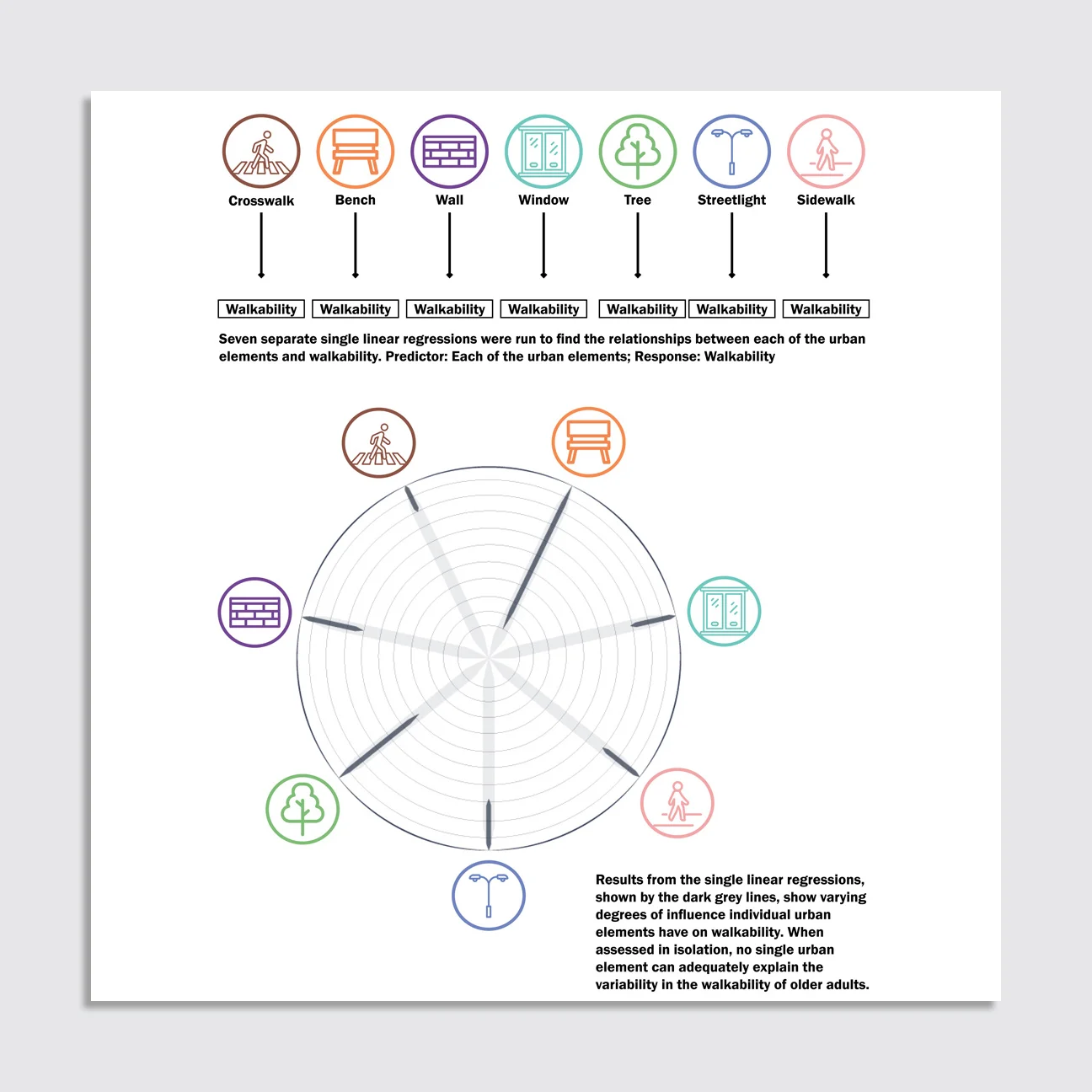

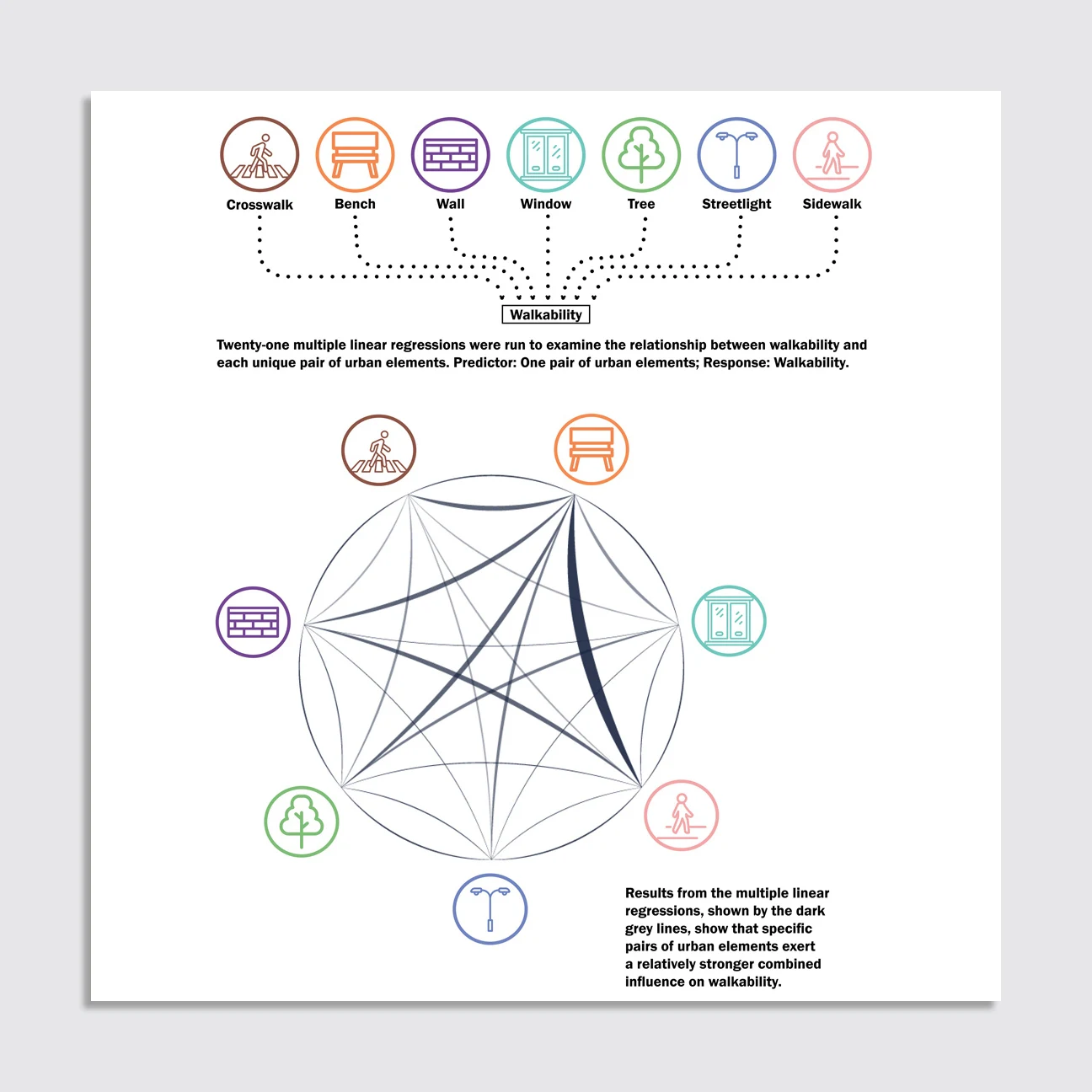

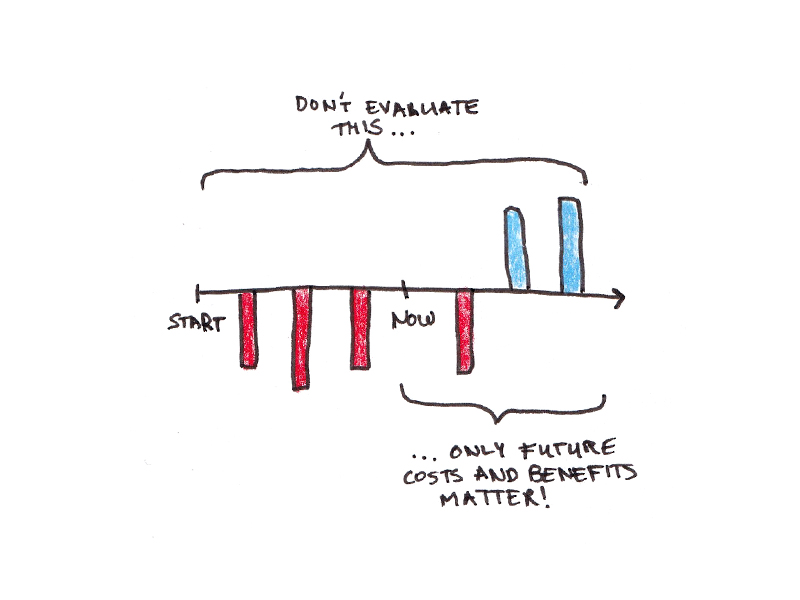

What the walkability study found is that people prefer to walk in places with a higher proportion of several basic streetscape elements, including benches, shade trees, sidewalks, and crosswalks. When those elements are provided in combination with one another—plentiful benches and crosswalks, for example—people are likely to walk even more.

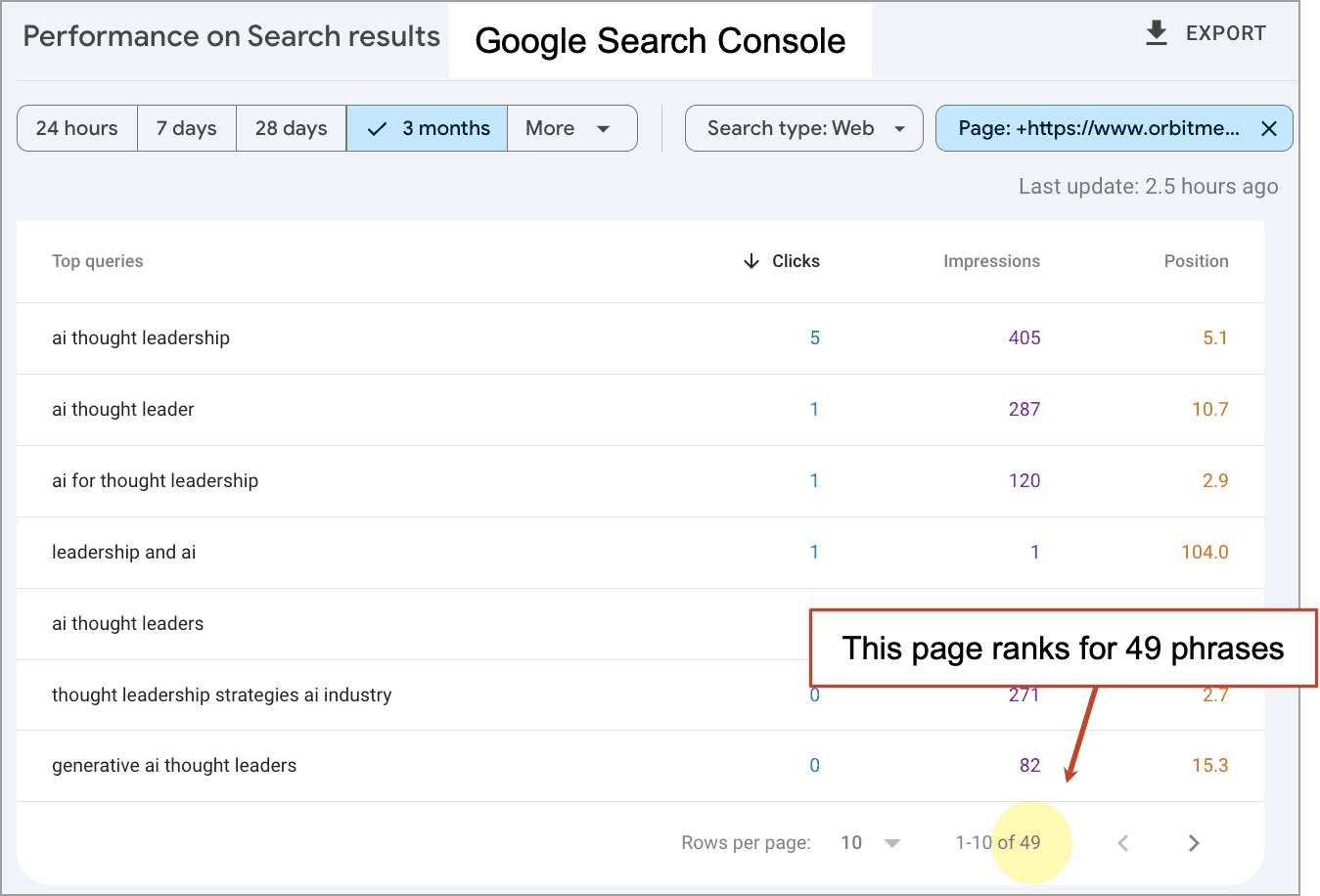

The study was based in the Kowloon district of Hong Kong, where a decennial survey collects detailed information from more than 100,000 pedestrians about the experience of walking through this part of the city. This survey data was analyzed alongside Google Street View imagery of the district to see what streetscape elements were predominant in places people reported being most likely to walk. This analysis led to a set of urban design guidelines that suggest ways of making more spaces more walkable.

The resulting study, “Are these streets made for walking?: How visual AI can inform urban walkability for older adults,” was led by Haozhou Yang, a student at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design who was a design and wellness research fellow at Perkins Eastman from 2023 to 2024. He says most previous walkability studies rely on zoomed-out data from geographic information systems (GIS), inferring walkability from data points like the existence of sidewalks or a neighborhood’s proximity to retail. “They’re not from the human perspective,” Yang says. “This [study] really puts the elements people encounter every day at the front.”

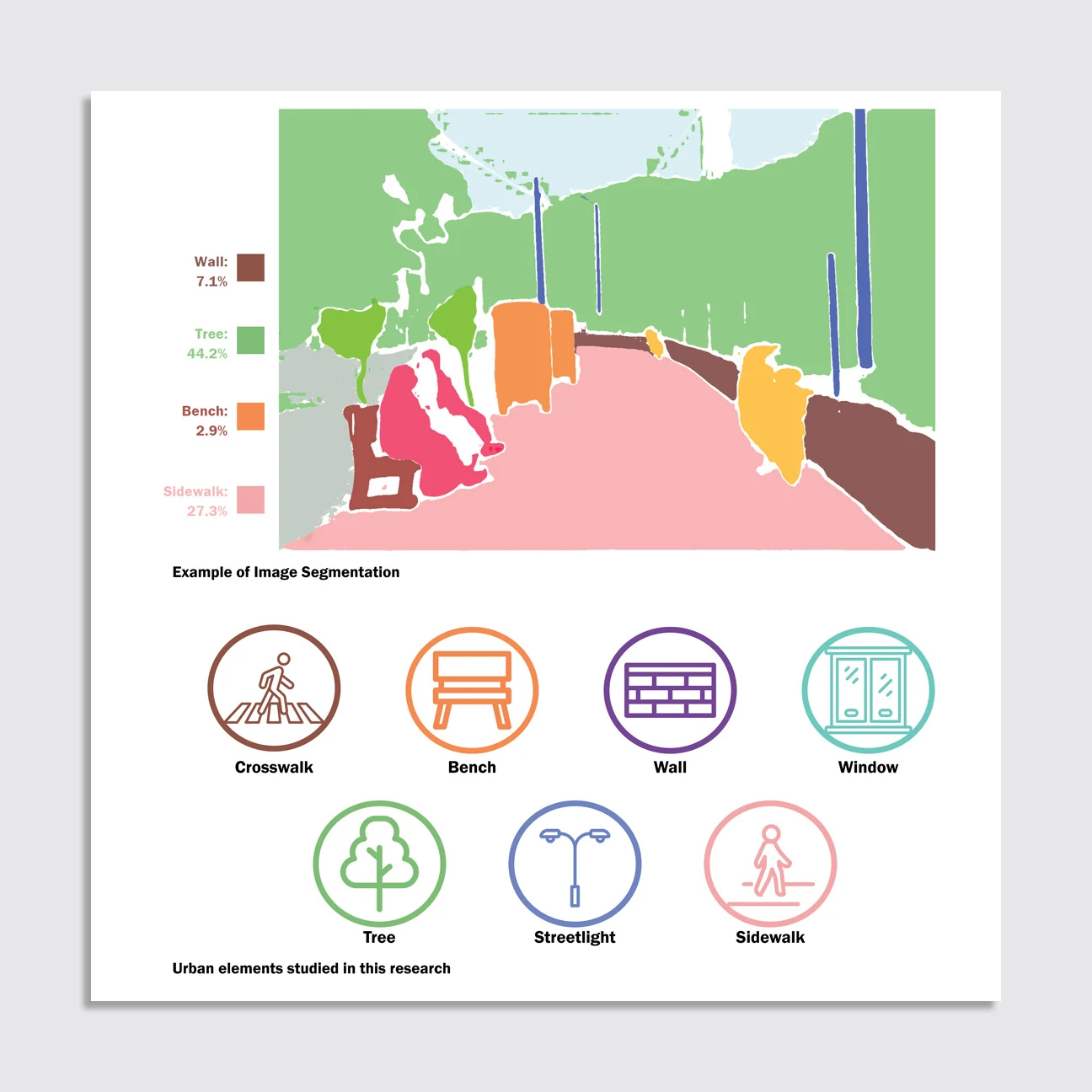

Google Street View offered Yang a deep pool of data about the real world conditions experienced by pedestrians in Hong Kong. His study used 32,512 images from Google Street View, separated throughout the district at 10-meter intervals. Machine learning techniques then broke each image down to identify individual streetscape objects within the frame and how much space they accounted for. One image might show tree canopy covering roughly half the image and sidewalk making up about a quarter. Other images show benches and walls. Still others highlight crosswalks and how much space is dedicated to car traffic.

“With new AI computer vision, we can really understand the quantifiable amount of those elements in the open environment,” Yang says.

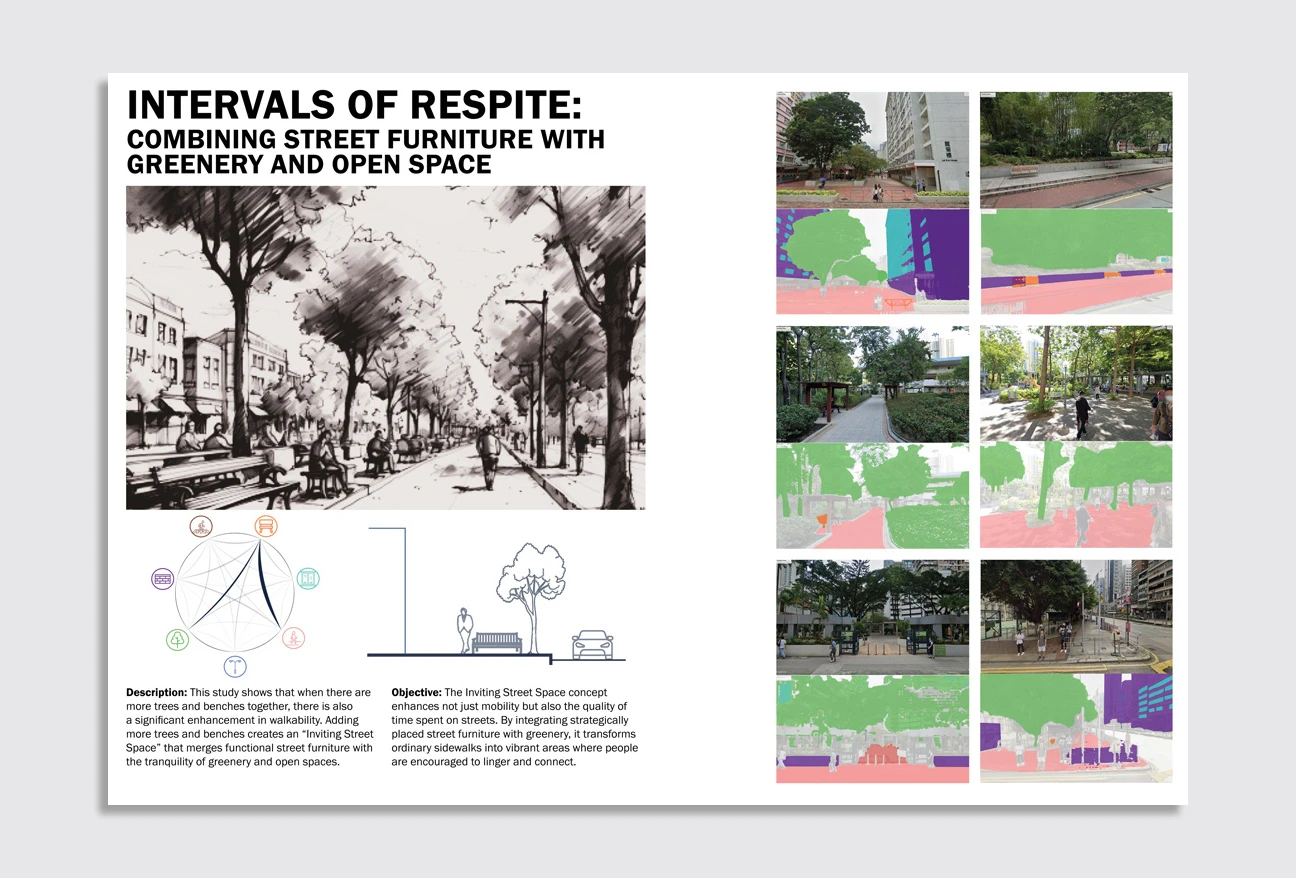

By focusing in on seven categories of streetscape elements—sidewalks, streetlights, trees, crosswalks, benches, walls, and windows—Yang and collaborators from Perkins Eastman were able to draw correlations between the presence and combination of those elements in places with high rates of pedestrian activity. These correlations then informed a set of urban design guidelines developed by Perkins Eastman’s senior living team. These guidelines include combining street furniture with greenery and open space, pairing crosswalks with improved street lighting, and increasing the social interactivity of a space by having more benches in areas with a higher amount of street-facing windows, balconies, and patios.

The study draws these connections through the lens of improving walking conditions for older adults, with the health and social benefits that come from being more mobile and independent. But the implications of the research are much broader, according to Perkins Eastman senior living principal Alejandro Giraldo. “These are things that are universal design,” Giraldo says. “It’s not just addressing the seniors. It absolutely will, but it’s also addressing people with mobility issues or children.”

Yang says that even though the data in this study is from Hong Kong, AI enables the model to be tuned or tweaked to the conditions in other cities, informing what might improve the walkability of that stretch along the Seine River or the side of that highway in Tallahassee. “Although there might be some cultural differences and context-related differences, the model can be applied to other cities,” Yang says.

For Perkins Eastman, which has designed senior living projects for more than 40 years, the designers are already looking at ways of integrating these findings into current and future projects and improving conditions for older adults. “You want to find the differentiator—as a community, as a developer group, as a resident—of what is making me live here,” Giraldo says. “To change the perception of aging is very critical for us. Demonstrating these tools allow us to create a more sensitive communities.”

![Building A Digital PR Strategy: 10 Essential Steps for Beginners [With Examples]](https://buzzsumo.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Building-A-Digital-PR-Strategy-10-Essential-Steps-for-Beginners-With-Examples-bblog-masthead.jpg)