Why AI Will Not Provide Sustainable Competitive Advantage

Boris Séméniako/Ikon Images There is no question that artificial intelligence will transform the competitive business landscape. AI will streamline business processes, increase worker productivity, redefine premium skill sets, and unlock the potential of data. There is also no question that AI will make relentless progress and become more capable at a dizzying pace. But AI […]

Boris Séméniako/Ikon Images

There is no question that artificial intelligence will transform the competitive business landscape. AI will streamline business processes, increase worker productivity, redefine premium skill sets, and unlock the potential of data. There is also no question that AI will make relentless progress and become more capable at a dizzying pace.

But AI will also become more ubiquitous. Algorithms and training data are being commoditized; hardware competition is fierce; talent is plentiful; open-source models reliably erode corporate offerings. AI will become increasingly economical to deploy, and competition will demand that companies do so. While it is impossible to predict exactly how AI will transform our economy, one thing is clear: Every company will want it, and there is essentially no reason why they will not be able to get it.

It is tempting for a company to believe that it will somehow benefit from AI while others will not, but history teaches a different lesson: Every serious technical advance ultimately becomes equally accessible to every company. Personal computers, the internet, semiconductor fabs, blockchain technology, genetic sequencing — these technologies are no longer competitive advantages for any organization.

AI is similar, and its increasing ubiquity should cause us to rethink our assumptions about how it will — and will not — change competitive dynamics. It is easy to paint a picture of a glistening, AI-driven future and the untold riches it harbors, ripe for the taking; it is just as easy to believe that companies that invest heavily in AI technology or move first will reap the lion’s share of potential profits.

But all such narratives obscure a critical point: While there will doubtless be transitory competitive advantages in embracing AI, AI does not change the fundamentals of what makes for a sustainable competitive advantage.

How can AI be the centerpiece of a sustained competitive advantage when everyone has it? We argue that it simply cannot. The value that AI unlocks will be unlocked for all. The advantages AI confers will be conferred on all. By definition, if everyone has access to the same technology — even if it is new and valuable — it may move the market as a whole but will not uniquely advantage anyone.

Far from being a source of differentiation, artificial intelligence will be a source of homogenization. Will AI perhaps unlock new creative possibilities, by helping to generate new product ideas, for example? Yes, and everyone who uses AI will be able to similarly boost their creative processes. Will AI perhaps unlock new productivity gains, by disrupting traditional software development, for example? Yes, and everyone who develops software will have access to those same gains. Will AI perhaps unlock new analytic possibilities, by surfacing new patterns in data, for example? Yes, and everyone with similar data will come to similar AI-driven conclusions. Part of AI’s value is that it is digital, and therefore it is fundamentally copyable, scalable, repeatable, predictable, and uniform.

Realistic thinking about this homogenization clarifies where a business should be strategically aiming for advantage. The leveling effect of AI will amplify the value of what we term residual heterogeneity — the ability of a company to go beyond what is accessible to everyone else and create something unique. It is not enough just to have AI; companies must still go beyond it. Therefore, the key to unlocking sustained advantage is the same as it always has been: Companies must cultivate creativity, drive, and passion. That creativity must be technical, involving research and development. It must include novel ways to use AI. But it also includes conceiving of novel partnerships and finding novel ways to connect with customers. These are the same pillars of innovativeness that have always distinguished great companies; AI does not change any of it.

Hurdles to Competitive Differentiation

AI can be at the center of a product, a strategy, or even a company’s DNA, but it cannot be at the center of a sustainable competitive advantage. Testing AI against the three defining aspects of a sustainable advantage reveals why: To be sustainable, an advantage must be valuable, unique to an organization, and inimitable by other businesses. If a technology is valuable but not unique, then it is not an advantage; similarly, if a technology is unique to a company but not valuable, it is not an advantage. If a technology is valuable and unique to a company but can be imitated by others, then it does not confer a sustainable advantage. AI is unquestionably valuable, but it fails the other two tests because it is neither unique to any organization nor inimitable.

Why might a company believe that the benefits of AI will somehow accrue to it but not to its competitors? Some reasons include access to capital or hardware, novel algorithms, advanced models, superior engineering talent, business insight, or proprietary data.

Dissecting each of these reasons reveals that none is sustainable. For example, while it is true that companies with access to the most capital and the largest GPU farms are training the largest and most capable AI models, scaling laws ensure diminishing returns and therefore ever-larger language models will be required; new models like GPT-4 and Gemini are only a few percentage points better than their predecessors on the standard benchmarks but required massive investments in data centers and engineering teams to get there.

Few industries progress as reliably as the semiconductor industry; it is only a matter of time before the hardware necessary to train even state-of-the-art models becomes more widely available. But it is also not clear that we need to wait: Smaller models that are accessible to almost anyone and can be trained relatively easily are relentlessly improving. Today’s models with only 7 billion parameters perform as well as yesterday’s models with 70 billion parameters. Differentiation is threatened from above and below.

Other factors are showing similar convergence and commoditization. Consider the mathematical models and training algorithms at the heart of AI. The AI research community has a strong history of sharing innovations and publishing key results, architectures, and software frameworks. This culture of openness, combined with strong academic interest in AI, ensures that fundamental algorithmic insights quickly get adopted by everyone. Or consider engineering talent. Because it is clearly valuable, the technical job market is unusually fluid. It is also becoming more crowded: Among computer science programs, AI Ph.D.s are being produced faster than any other type. Computer science and AI are also unique among disciplines in terms of the sheer volume of freely available online materials that learners can use to bootstrap their skills. Both high-end and entry-level talent will not be scarce for long.

Perhaps the strongest bulwark protecting a company’s AI advantage is proprietary data, but even here, pressures unique to AI are eroding its inimitability. Almost all models derive most of their training data from the same data sets (open or licensed) and therefore perform about the same. Synthetic data is on the rise, and though it is not yet a true substitute for real data, it is already improving models and reducing their costs. Everyone agrees that AI models are statistically inefficient and require more data than they should; the AI research community is working intensely to fix this, suggesting that merely having big data will not be sufficient protection for long. AI models are also becoming generalists that are broadly competent and can be easily adapted to proprietary tasks. The intersection of these trends suggests that only a small amount of proprietary data will be needed to adapt AI models to perform new functions, which will be easily obtainable.

The lowering costs of implementing AI, combined with a general convergence of the technology stack, suggests that companies need to look elsewhere for sustainable advantage.

The Value of Residual Heterogeneity

We have argued that a wide array of pressures will lead to ubiquitous AI, which will in turn lead to a homogenizing of business capabilities that will benefit all of society but will not drive sustainable differentiation. Where, then, should a company strategically aim for competitive advantage? The key is to remember the fundamental nature of innovativeness, which remains the same regardless of how any technology reshapes society: creativity at the boundary of what is possible.

As AI homogenizes products and services, the greatest value will lie in residual heterogeneity. Consider an extended example. Multiple startups are currently racing to use generative AI to create low-cost digital mental health therapists; these businesses will be classic disruptive innovators, easily dominating the bottom of the market by filling unmet demand for therapy. The nature of language models ensures that these products will be cheap and scalable and will compete well with human therapists in low-stakes settings.

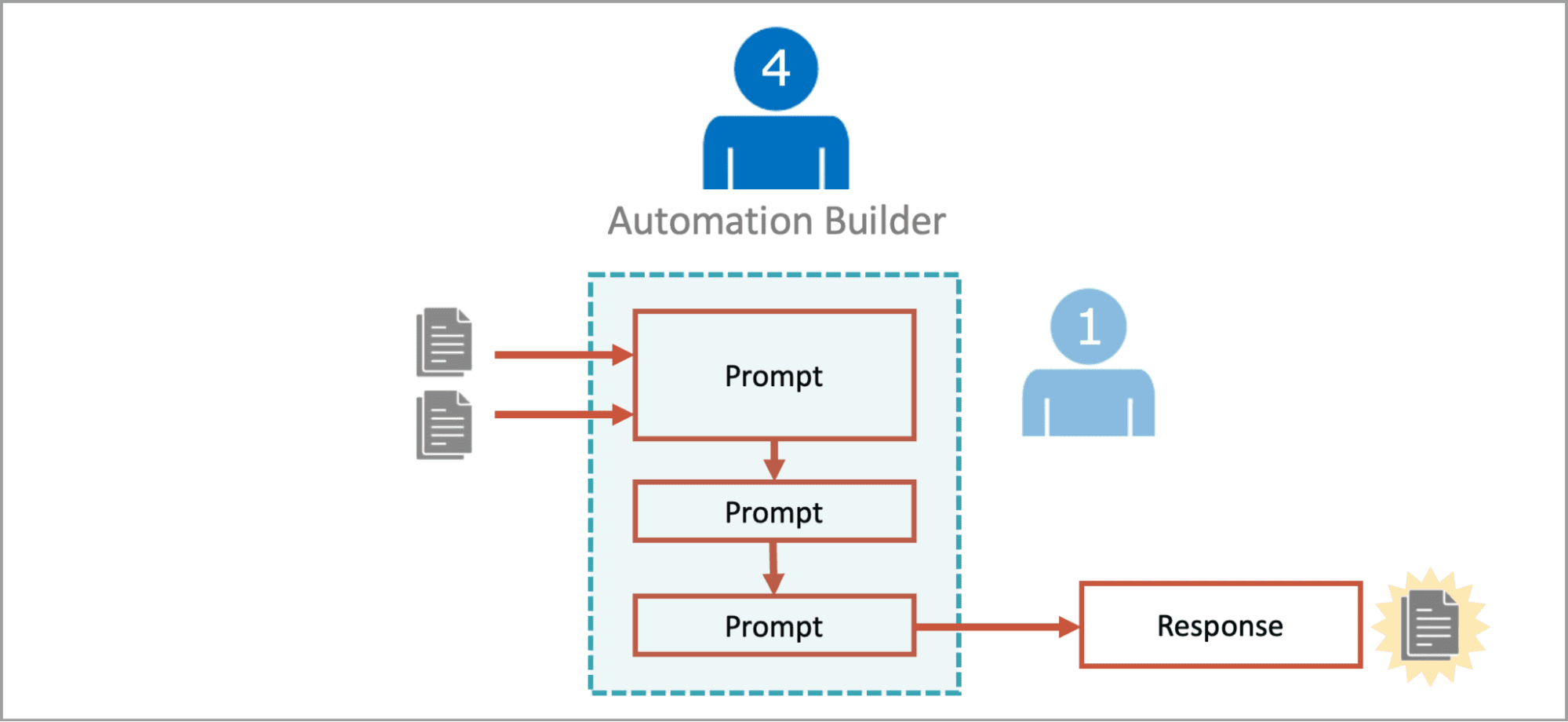

But all of these companies will build on AI platforms provided by tech giants (or cheaper open-source models). Those platforms are more similar than they are dissimilar, and, as a result, all of these silicon therapists will perform about the same. Which provider will stand out in the market? Initially, it may be the company that develops the best prompt, most thoroughly tests its system to root out potentially harmful behavior, or fine-tunes on the best real-world therapy transcripts, but ultimately the sustainable advantage will go to the companies that invest in factors beyond the AI technology. It may be that the company consistently cultivates novel business relationships that provide access to targeted patients. It may be that the company builds a grassroots network of customers by engineering relationship-based referrals. It may even be that the company frictionlessly delivers its services via social media. Whatever it is, its advantage will not be an advance in the AI itself; that advantage will evaporate quickly.

Similar analyses apply to companies using AI to automatically generate marketing materials, drive drug discovery, or revolutionize artistic content creation. The long-term value will always be found by those that are differentiating at the boundary of what is possible, and it will be the fundamental patterns of human creativity and relationships that drive that creativity. This is because while AI is excellent at interpolation, it still lags humans in extrapolation. AI algorithms are adept at finding patterns in their training data and in combining and recombining those patterns in new and interesting ways. For example, generative AI art tools excel at copying the style of existing artists and can even blend multiple extant styles together — but they struggle to define new, primal styles. Similarly, language models can produce arithmetic facts but cannot solve arbitrary problems because they do not construct a world model capable of extrapolation.

In contrast, fundamental hallmarks of human intelligence — the ability to see novel possibilities, forge unexpected connections, and make leaps of logic — are still unmatched by AI. Human creativity will be the greatest source of sustainable advantage companies can rely on in an uncertain world, and companies must not lose sight of the individuals and relationships that drive that creativity. Investing in untapped individual potential, promoting training and upskilling, and rewarding innovation will result in human capital that can sustain companies no matter how the technological landscape morphs.

The great companies that were built before the era of AI need to remember what — and who — it was that got them there. Drive, passion, and ingenuity are still uniquely human, and developing and focusing that energy where it matters most should be a key element of any long-term business strategy.