When Team Accountability Is Low: Four Hard Questions for Leaders

Sidsel Sorensen/Ikon Images I once had to take a bleeding coworker to urgent care. It was a harrowing incident. He had cut himself on a broken mug that tumbled from a kitchen cabinet, and his hand wouldn’t stop gushing blood. What struck me wasn’t how hurt you can get from a silly accident but how […]

Sidsel Sorensen/Ikon Images

I once had to take a bleeding coworker to urgent care. It was a harrowing incident. He had cut himself on a broken mug that tumbled from a kitchen cabinet, and his hand wouldn’t stop gushing blood. What struck me wasn’t how hurt you can get from a silly accident but how hard it was to nail down who should help him.

It’s not always immediately clear who’s accountable at work.

I think about this incident a lot as I hear leaders tell me, over and over, that a lack of accountability on their team is the workplace behavior that concerns them the most. These leaders, sometimes exhausted and despairing, feel that their teams cannot take ownership of even the smallest tasks.

What’s going on here? Is accountability in short supply these days? Did someone wave a magic wand and make us all suddenly not accountable?

Are we all a bunch of flakes?

No, we are not.

It turns out that some concrete evolutions in how we work are making personal accountability in the workplace a tougher challenge. Now, true to an article on accountability, I’m not letting anyone off the hook here … but we’re not going to solve for it simply by shaking our index fingers at folks and scolding them to “be more accountable!”

Rather, a leader needs to understand what’s stopping folks from behaving accountably and then overcome those challenges. But there is some bad news: You may have to actively disrupt some of your own long-held behaviors as well.

Think of these moves as “circuit breakers” — shutting the whole system down and bringing it back up with responsible actions built into your organization’s modus operandi.

Accountability Question 1: Are too many people involved?

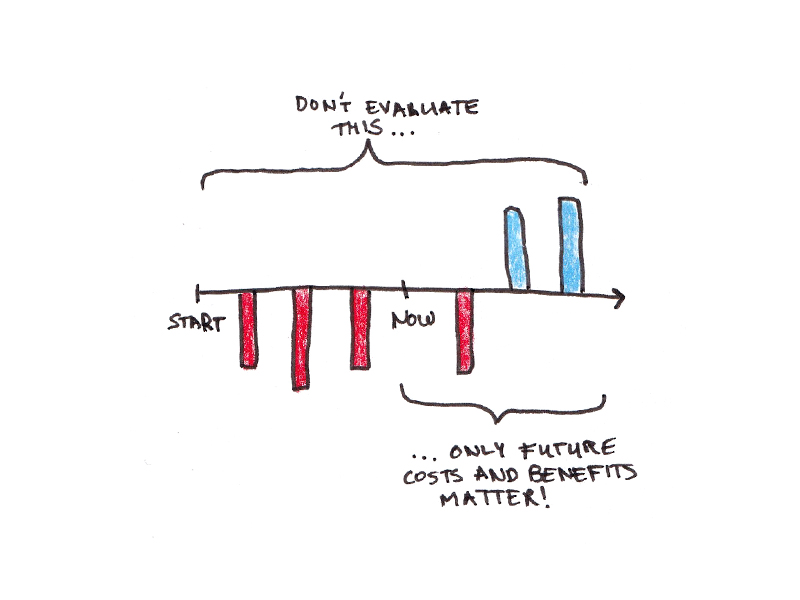

We all know the old adage “When everyone’s responsible, no one’s responsible” — commonly referred to as the “tragedy of the commons” and often cited by workplace scientists like Cal Newport as a systemic issue for knowledge work. Today, though, the “everyone” often multiplies even further due to technology.

Consider a highly simplified example: In the days of completely in-person meetings, you could have only as many attendees as would fit in the room. Maybe you’d run out of chairs and have a few folks perch on the table in the back with the muffins and coffee, but effectively, there was a limit.

Now consider an online meeting. Teams or Zoom can accommodate up to a thousand people. A thousand! Meeting planners note that you need about 20 square feet per person in a physical meeting room, so a thousand-person meeting would require a 20,000-square-foot conference room … 100 times the size of the average 200-square-foot conference room. On a brute-force basis, you’re 100 times less constrained on meeting size.

Now, most of us are not in 1,000-person virtual meetings — town halls, perhaps, but not actual meetings. But meeting size in a virtual space — without that “conference room” constraint — regularly goes into the dozens — and this exceeds a sensible number of people. We don’t consider it weird to virtually meet with three or four conference rooms’ worth of people, but we should.

Next, let’s start talking about how many folks were copied on the last email you received. With large crowd sizes being normalized, it is genuinely difficult to discern individual accountability. It’s hard to look at an email with 26 people in the cc: field, or sit in a meeting with 35 people and say, “I’m on the hook here. I know exactly what I, specifically, need to do.”

The circuit breaker: Form subcommittees or squads.

It can be politically challenging within organizations to disrupt the unhelpfully large teams being assembled. But as a leader who wants people to take accountability to get stuff done, you must. Start forming smaller squads around discrete tasks. Truly want that problem solved? Get four to eight people on it — the much-vaunted two-pizza-box team.

Explicitly announce the subcommittee or squad formation and then, folks … use technology to bar the door! You can set up meeting invitations that cannot be forwarded and emails where people cannot be added to the cc: line. This can feel like a very bold statement, but if the team understands that staying small is part of their mandate, they’ll welcome a little peace and quiet to get stuff done.

Accountability Question 2: Are too many things going on at once?

Are you sensing a theme of “too muchness” here? Beyond the issue of “too many people,” we have the issue of “too many things.” Time to look in the mirror here, leaders.

I once sat with an executive team where a leader was complaining to the CEO that they had 37 priorities. This had to be a figure of speech or an exaggeration, right? Nope, this leader actually had a list of 37. Now take those 37 priorities and add a few workstreams to each, along with resulting actions and second-order actions, and you’re into hundreds of resulting tasks stemming from just the organization’s core priorities — before you even get into the stuff that pops up day to day. As that employee, if you have dozens of things on your plate, how do you decide which of the dozens of things you’re truly accountable for? How do you even pick what to do first?

Unfortunately (and unhelpfully), leaders often frame the issue of “too many things” as an individual productivity challenge. It’s not that we gave you too many disparate things to do that have no connection to each other, and no sensemaking framework for prioritization, and a bunch of people freaking out that you didn’t address their own personal priority first. No — it’s you! You’re not good at prioritization. You should be able to effortlessly figure out the complex restacking of tasks at a moment’s notice and fend off angry notes crashing into your inbox and chat apps without breaking a sweat.

Let’s stop gaslighting folks. What you think looks like less-than-accountable behavior may be people desperately trying to keep their heads above water. On that theme, think of the common misconception that drowning is a loud activity where people wave their arms and shout. In fact, when someone is actually drowning, their body expends all of its energy just trying to stay afloat. Drowning people stay quiet and conserve motion. No yelling, no flailing.

Similarly, people overwhelmed by too many disparate tasks often aren’t hollering — they’re quietly dodging the next wave. You’re not witnessing an accountability failure: You’re seeing the natural impacts of an overloaded system.

The circuit breaker: Kill or automate the work that makes the least sense.

As a leader, you may be swimming in the same crashing waves yourself. It can feel incredibly daunting — even politically impossible — to pare down long lists of “what we think has to get done” into lists of “what truly has to get done.” Don’t try to spot nonsensical work being done by each individual. Instead, go after categories of truly obviously bad work.

Performative work is one such category. This is work that’s just for show — a performance in the theatrical, not the athletic, sense. Often, it’s “work about work”: overanalyzing or overdocumenting existing work. Some of this can be automated: You can use an AI tool to summarize meetings instead of having a junior person do it (or, worse, a senior leader who’s seeking to take credit for the meeting).

For the rest, spark an ongoing discussion about “can we do without ____?” Oftentimes, there are entire initiatives that no one values, but no one wants to speak up first. Having an ongoing discussion about fighting bureaucracy (who could argue?) gives you a platform to kill bad work. This positions you to rally people to take more accountability for the work everyone does value.

Accountability Question 3: Are roles within teams unclear?

Ambiguous or fuzzy roles within teams can create a particularly frustrating accountability challenge: People actually know they’re accountable for something, in aggregate, but cannot figure out the specific piece of it they’re supposed to tackle. They’re this close to accountability but a million miles away at the same time.

Another fascinating wrinkle: These fuzzy roles within teams are often assigned by well-intentioned managers who are trying to avoid micromanagement. In pursuit of this laudable goal, the leader errs on the side of not giving enough clarity as to how work should get done.

There’s a pervasive cultural myth about agile teams where everyone just magically knows how to get something done. In reality, no one with a working knowledge of agility, Agile, or teams would actually recommend this organizing structure. After all, if you don’t know that you’re a point guard, a first baseman, or a soccer goalie, how do you know what to do with the ball? Similarly, teams without clear roles may seem unaccountable, but they’re just full of people trying to figure out who to throw to and when.

The circuit breaker: Don’t assign work collectively without a roles discussion, each and every time.

Warning: This leadership move will feel strange. The first few times you step in to clarify who’s responsible for which piece of what, it may feel ridiculously basic or didactic. However, you can do this in a very open-ended fashion: “Just so we’re clear on what we need … help me get a sense of who’s grabbing which piece?” It may feel awkward, but you’ll be shocked at how many times the team is not clear on who’s going to do what — and a productive, accountability-driving discussion will result.

Accountability Question 4: Did you ask people to do something silly — and no one will tell you the truth?

We’ve reached the “tough love” portion of this article.

Sometimes, when it looks like people are not taking accountability, and things are not getting done, it’s because whoever you asked to do the thing truly thinks it would be a bad idea to do that thing.

And they’re afraid to tell you.

Afraid may be too strong a word. People may hesitate to take up your time to discuss something they consider to be of questionable value; they may assume that you know better than they do and that there’s some logic they’re missing. Or they may genuinely fear professional consequences for pushing back against you.

In any of those cases, they’re not going to tell you “no,” but they’re also not going to do the task. Their behavior reads as a lack of accountability but, in fact, they’re trying to be accountable to outcomes by quietly saving you from your own bad ideas.

The circuit breaker: Be the boss people can talk back to, within reason.

You don’t have to be a doormat, a pushover, or even the person whose office (physical or virtual) people go to to cry. But in an age of transparent, information-rich workplaces, a “brick wall” style of management doesn’t get you anywhere either.

If people feel that they can’t raise objections to what they’re being asked to do or how they’re being asked to do it, you’re missing critical information that could help you and your team perform better.

Don’t wait for seeming accountability failures before you course-correct. Signaling that you care about input can be as simple as this: When you ask people to do something, ask them whether they would approach it differently. Do they agree with the action itself? Do they agree with the basics of how to do it? To do this properly, you then must follow through by shutting up, listening, and acting on at least one piece of feedback you get back. Do this every time, and people will help you do your job really, really well. And they’ll become more accountable because they helped set the right course.

Getting accountability right isn’t rocket science: It’s small teams with clear priorities and roles, led by a leader who can edit their own approach in response to feedback. Get these structural mechanisms in place systematically, and you’ll be shocked at how accountable your team is capable of being. And the next time there’s a real crisis — though, hopefully, not someone bleeding — you’ll be grateful you set the accountability machine into motion.

![How One Brand Solved the Marketing Attribution Puzzle [Video]](https://contentmarketinginstitute.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/marketing-attribution-model-600x338.png?#)

![Building A Digital PR Strategy: 10 Essential Steps for Beginners [With Examples]](https://buzzsumo.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Building-A-Digital-PR-Strategy-10-Essential-Steps-for-Beginners-With-Examples-bblog-masthead.jpg)

![How to Use GA4 to Track Social Media Traffic: 6 Questions, Answers and Insights [VIDEO]](https://www.orbitmedia.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/ab-testing.png)

![[HYBRID] ?? Graphic Designer](https://a5.behance.net/cbf14bc4db9a71317196ed0ed346987c1adde3bb/img/site/generic-share.png)