Why taste matters now more than ever

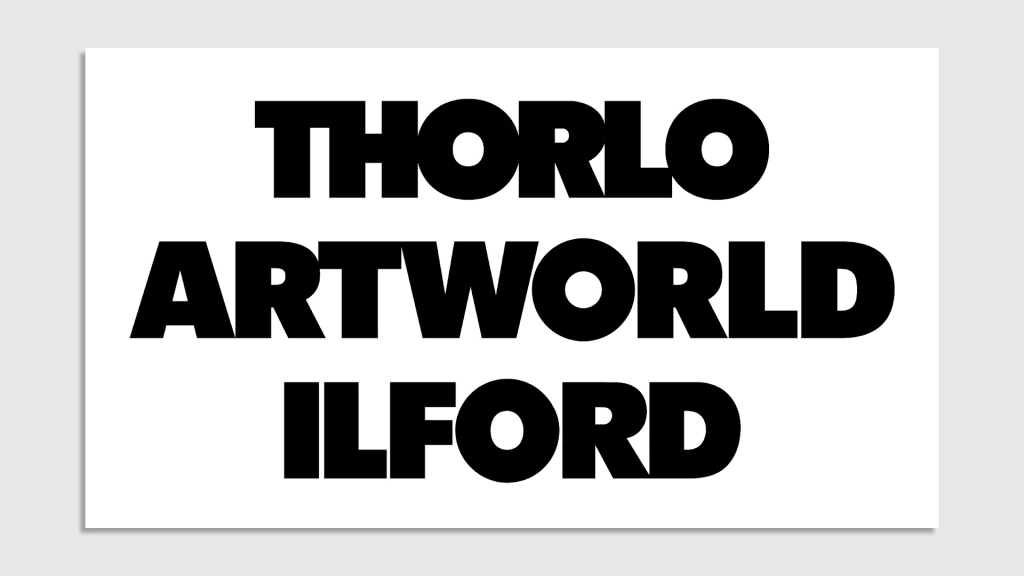

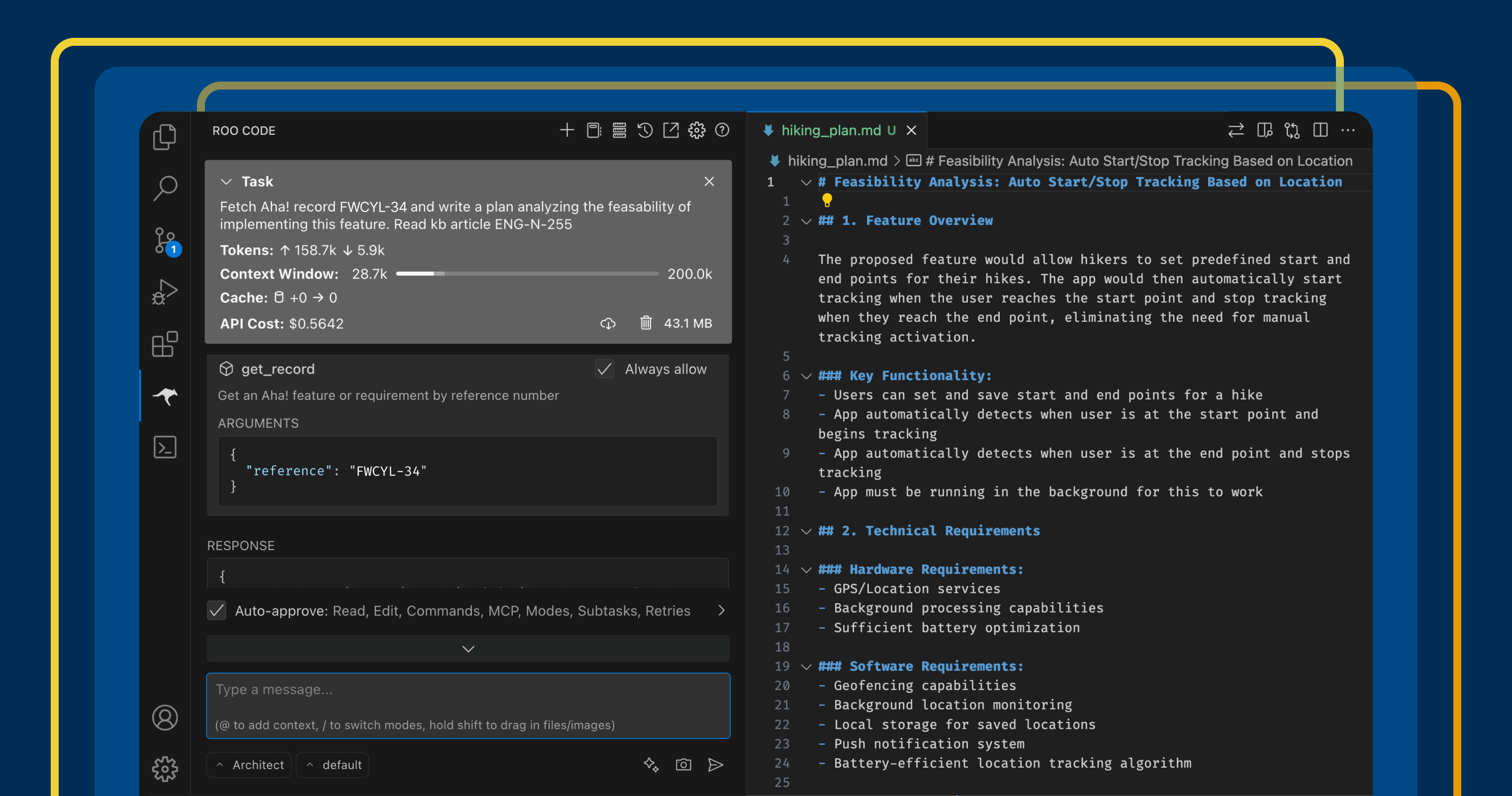

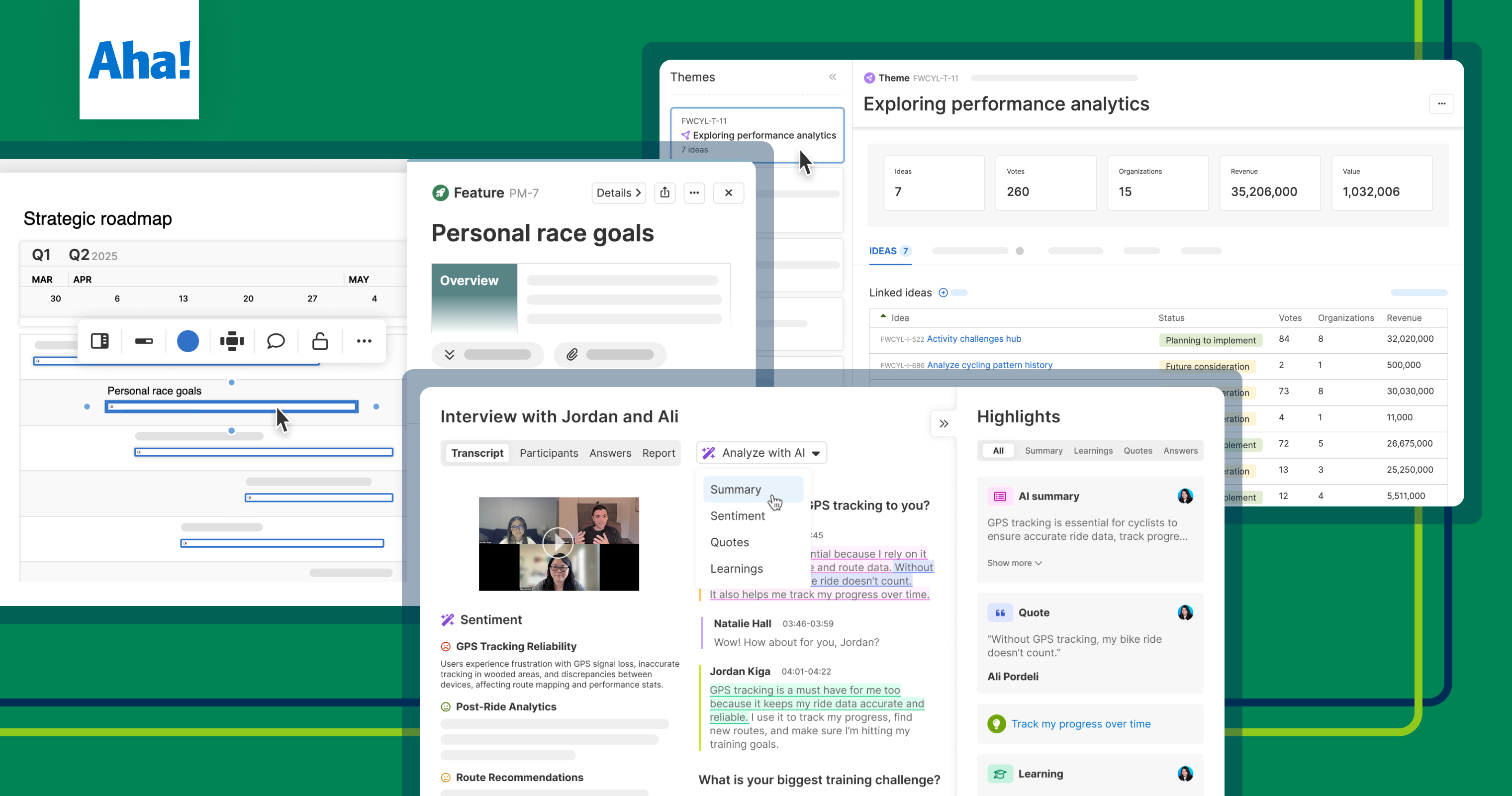

It’s easy to get swept up in headlines predicting the end of the design industry as we know it. It’s true: AI tools can now generate in seconds what once took days for teams of designers. So it’s no longer a question of whether these tools will be used—but how, why, and by whom. If design as we know it is being automated, what remains? And what becomes more valuable? In the 1930s, cultural critic Walter Benjamin argued that mechanical reproduction—photography, film, the printing press—was transforming not just how art was made, but how it was perceived. His concern wasn’t just about losing originality or craft; it was about losing aura—the sense of presence that comes from a work’s connection to time, place, and purpose. When something can be reproduced endlessly, that connection starts to dissolve. And in the post-internet world, it’s all but collapsed—context has become slippery, distributed, and flattened. The role of creative direction, then, is to restore that lost dimensionality—to place things, to anchor them in context. The craft of execution is no longer a differentiator. For surface-level visuals, speed and quantity now rule. But this shift reveals something deeper: When production is automated, the designer’s role becomes less about making and more about meaning. I’ve felt this shift firsthand. At the outset of my career, I spent hours—days—in Photoshop extending backgrounds, removing objects, and meticulously cutting out product images for e-commerce sites. It was repetitive, yes—but also meditative. There was a quiet satisfaction in working with images by hand, pixel by pixel. That kind of technical work is now (thankfully) almost entirely automated. Although I miss blocking off an afternoon to push pixels, the ability to delegate those tasks means I no longer need to dedicate time to erasing shadows—I spend that time deciding what the image should say in the first place. Not all design disciplines are equally affected by AI. Those who work with material, scale, and space—book designers, muralists, sign painters, mosaicists—continue to operate through tacit knowledge and touch. Their work still resists automation because it’s rooted in place and presence—it has “aura.” But even in brand design, something similar holds true: The more a designer’s value is bound to personal taste, knowledge of context, and aesthetic judgment, the more durable it becomes. It’s tempting to hold onto the idea of the designer as auteur, untouched by context. But that belief overlooks how meaning is actually made: not by the author alone, but in conversation with culture, with tools, with audience. Mistaking authorship for authority leads to stagnation. If you’re a designer today, your ability to thrive depends on shifting your creative identity from executor to editor, and from technician to translator. The cost of not adapting isn’t just irrelevance. It’s being indistinguishable from the tools themselves. As Chris Braden, my former CCO at Public Address, has said: “In nature, things that don’t move are dead.” Virgil Abloh, Pyrex Vision Rugby Flannel (2012). Abloh bought Ralph Lauren shirts from outlet stores, screen-printed “PYREX 23” across the back, and sold them at a premium, reframing authorship through minimal intervention. [Image: ©Pyrex Vision] Which is why creative direction matters more now than ever. If designers are no longer the makers, they must become the orchestrators. This isn’t without precedent. Rick Rubin doesn’t read music or play instruments. Virgil Abloh was more interested in recontextualizing than inventing. Their value lies not in original execution but in framing, curation, and translation. The same is true now for brand designers. Creative direction is about synthesizing abstract ideas into aesthetic systems—shaping meaning through how things feel, not just how they look. This opens up a new kind of opportunity for ideas to come from more rigorous places—critical theory, art history, cultural analysis—without being stripped of their richness. AI can absolutely help translate complex ideas into accessible ones. But it’s the designer who chooses which ideas to bring forward, how to apply them, and why they matter in a given moment. That’s not just a function of intelligence—it’s a function of intuition, authorship, and taste. Taste isn’t just personal preference. It’s an evolving, often unstable framework—shaped by experience, exposure, and the cultural moment—that informs how we make aesthetic judgments. It’s not fixed, nor is it singular. What feels resonant in one context may fall flat in another. Taste is less about knowing what’s right and more about understanding what’s relevant—what aligns, what disrupts, what works now. In a world of infinite possibilities, taste becomes less of a crown and more of a compass. Top to bottom: Thorlo by High Tide NYC (2023), Artworld by Mouthwash Studio (2020), Ilford by an unknown designer (1997). They’re nearly identical,

It’s easy to get swept up in headlines predicting the end of the design industry as we know it. It’s true: AI tools can now generate in seconds what once took days for teams of designers. So it’s no longer a question of whether these tools will be used—but how, why, and by whom. If design as we know it is being automated, what remains? And what becomes more valuable?

In the 1930s, cultural critic Walter Benjamin argued that mechanical reproduction—photography, film, the printing press—was transforming not just how art was made, but how it was perceived. His concern wasn’t just about losing originality or craft; it was about losing aura—the sense of presence that comes from a work’s connection to time, place, and purpose. When something can be reproduced endlessly, that connection starts to dissolve. And in the post-internet world, it’s all but collapsed—context has become slippery, distributed, and flattened. The role of creative direction, then, is to restore that lost dimensionality—to place things, to anchor them in context.

The craft of execution is no longer a differentiator. For surface-level visuals, speed and quantity now rule. But this shift reveals something deeper: When production is automated, the designer’s role becomes less about making and more about meaning.

I’ve felt this shift firsthand. At the outset of my career, I spent hours—days—in Photoshop extending backgrounds, removing objects, and meticulously cutting out product images for e-commerce sites. It was repetitive, yes—but also meditative. There was a quiet satisfaction in working with images by hand, pixel by pixel. That kind of technical work is now (thankfully) almost entirely automated. Although I miss blocking off an afternoon to push pixels, the ability to delegate those tasks means I no longer need to dedicate time to erasing shadows—I spend that time deciding what the image should say in the first place.

Not all design disciplines are equally affected by AI. Those who work with material, scale, and space—book designers, muralists, sign painters, mosaicists—continue to operate through tacit knowledge and touch. Their work still resists automation because it’s rooted in place and presence—it has “aura.” But even in brand design, something similar holds true: The more a designer’s value is bound to personal taste, knowledge of context, and aesthetic judgment, the more durable it becomes.

It’s tempting to hold onto the idea of the designer as auteur, untouched by context. But that belief overlooks how meaning is actually made: not by the author alone, but in conversation with culture, with tools, with audience. Mistaking authorship for authority leads to stagnation. If you’re a designer today, your ability to thrive depends on shifting your creative identity from executor to editor, and from technician to translator. The cost of not adapting isn’t just irrelevance. It’s being indistinguishable from the tools themselves. As Chris Braden, my former CCO at Public Address, has said: “In nature, things that don’t move are dead.”

Which is why creative direction matters more now than ever. If designers are no longer the makers, they must become the orchestrators. This isn’t without precedent. Rick Rubin doesn’t read music or play instruments. Virgil Abloh was more interested in recontextualizing than inventing. Their value lies not in original execution but in framing, curation, and translation. The same is true now for brand designers. Creative direction is about synthesizing abstract ideas into aesthetic systems—shaping meaning through how things feel, not just how they look.

This opens up a new kind of opportunity for ideas to come from more rigorous places—critical theory, art history, cultural analysis—without being stripped of their richness. AI can absolutely help translate complex ideas into accessible ones. But it’s the designer who chooses which ideas to bring forward, how to apply them, and why they matter in a given moment. That’s not just a function of intelligence—it’s a function of intuition, authorship, and taste.

Taste isn’t just personal preference. It’s an evolving, often unstable framework—shaped by experience, exposure, and the cultural moment—that informs how we make aesthetic judgments. It’s not fixed, nor is it singular. What feels resonant in one context may fall flat in another. Taste is less about knowing what’s right and more about understanding what’s relevant—what aligns, what disrupts, what works now. In a world of infinite possibilities, taste becomes less of a crown and more of a compass.

It’s no longer enough to know what’s trending from scrolling your various feeds. As Abloh understood, when originality becomes obsolete, novelty comes from recombination, from juxtaposition: from having a point of view. If your value lies in how you see—and how you help others see—that’s not just algorithm-resistant. It’s literally irreplaceable.

AI is a tool—but like all technologies, it’s not neutral. It reflects the choices of its makers and transforms every system it touches. It influences markets, media, and belief. It expands what’s possible while quietly reshaping how meaning is made. And its impact on creative work is especially complex. It’s a medium, a system, a collaborator. It can generate, iterate, and surprise. But it can’t decide what matters. It can’t assign meaning. It can’t make a choice. AI responds to input. Creative direction is that input.

This shift raises real questions for the future of design education and hiring. What does a portfolio look like when visuals are no longer enough? Increasingly, it might look less like a finished book and more like a screenplay: a series of prompts, iterations, references, and decisions that show how a designer directed a process, not just executed an outcome. The goal isn’t to hide the machine but to show how it’s been used with intention.

We’re moving into an era where synthesis and judgment—not just execution—are the creative differentiators. AI will continue to evolve, and yes—it will replace certain tasks and even entire roles. But it won’t replace curiosity. It won’t replace intuition. And it won’t replace the ability to decide what matters.

![Building A Digital PR Strategy: 10 Essential Steps for Beginners [With Examples]](https://buzzsumo.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Building-A-Digital-PR-Strategy-10-Essential-Steps-for-Beginners-With-Examples-bblog-masthead.jpg)

![How One Brand Solved the Marketing Attribution Puzzle [Video]](https://contentmarketinginstitute.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/marketing-attribution-model-600x338.png?#)